Inside Ocean Hill–Brownsville : A Teacher’s Education, 1968–69

Charles S. Isaacs, SUNY Press Excelsior Editions, 2014, 364pp. ISBN 978-1-4384-5296-8, USD $29.95

Sharon J. Hardy & Audra M. Watson

Graduate Center, The City University of New York

Paying homage to the extraordinary happenings of an embattled and embittered 1960’s New York City, Charlie S. Isaacs chronicles events that embroiled the City’s schools. Isaacs offers a detailed account of the fight for an active community role in the City’s public schools from ground zero, inside Junior High School 271 in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville section of Brooklyn as the community shifted from a Jewish to predominantly black population by the late 1960s.

In Inside Ocean Hill-Brownsville: A Teacher’s Education, 1968-69 Isaacs describes his introduction to the realities of public schools in underserved communities during his early days as an energetic and enthusiastic 22-year old novice teacher. Contrary to other published accounts of the tumultuous series of teachers’ strikes lead by the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), Isaacs takes readers behind the protest barriers and into classrooms in order to illustrate both the successes and travesties borne from a community’s struggle for quality schools.

Isaacs organizes Inside Ocean Hill-Brownsville in three primary sections: an historical overview of the political and social factors leading up to the teachers’ strike; Isaacs’ personal accounts of conversations and events during the strikes; and finally his synopsis of the strikes’ aftermath which served to influence New York City public school policy and practice nearly two generations later.

Isaacs sets the stage with New York City’s continued blatant practice of segregation in its public schools despite the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown vs Board of Education ruling. Isaacs states, “The overarching crisis was the inferior education that plagued the segregated black and Puerto Rican schools (pg. 7)…Ocean Hill-Brownsville is the story of a battle to combat domestic colonialism by a community seeking power and self-determination (pg. 68).”

A recent college graduate and first-year law student in Chicago, Isaacs found the course of his professional life redirected from lawyer to teacher when he responded to a national call for urban teachers. Isaacs writes, “Many came to Ocean Hill-Brownsville with a fast-track teaching license, and possessed neither experience nor formal training to prepare them for the job (pg. 46). Isaacs’ accelerated teacher preparation consisted of a two-week course in the Philosophy of Education and various Board tests, which he passed easily.

The racial tension in 1960’s New York is palpable in Isaacs’s description of the political strife surrounding Ocean Hill-Brownsville and the community control experiment. Underserved black and Latino communities were finding their voice and organizing strength under the leadership of educators and activists such as Rhody McCoy and Milton Galamison. Isaacs writes that the consensus was that, “…the city’s schools would never be desegregated, and that they would continue to fail black and Puerto Rican children unless some radical change was introduced” (pg. 49).

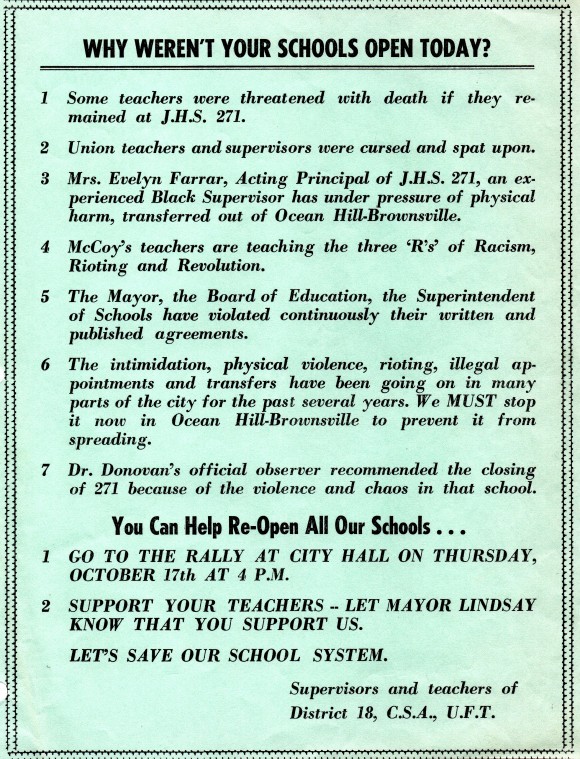

Hired as a mathematics teacher at JHS 271 by Rev. C. Herbert Oliver, the governing board chairman, Oliver made an impression on Isaacs that would shape his immediate devotion to the JHS 271 community despite being a community outsider. Isaacs described his job interview with Oliver noting, “He made me feel like a welcome guest in his home” (pg. 49). It is Isaacs experience from that moment of hospitality and shared goal in student achievement that would play an integral part in defining for Isaacs his role and place as a teacher. Isaacs is critical of the UFT leadership and its “teachers who had sabotaged the community control experiment, and whose union held the entire city hostage in its crusade to destroy that effort” (pg. 50). Isaacs does not suppress his disapproval of Albert Shanker’s manipulative leadership of the UFT nor does he conceal his antipathy of the actions of the mainstream press and its biased portrayal of the black and Puerto Rican communities. Both, according to Isaacs, added fuel to the already smoldering flames surrounding the fight for power and control over not just the City’s schools, but over the destiny of its students. Disappointed by Shanker’s exploitation of the UFT to serve his personal agenda Isaacs writes, “They considered us traitors not only to the teaching profession, but to the white race” (pg. 130).

In recounting the events, Isaacs challenges the published accounts on the Ocean Hill-Brownsville strikes by Jerald Podair and Diane Ravitch and blasts what he deems an irresponsible perpetuation of distorted facts retold from a biased press. Isaacs writes, “The UFT-driven media image of what happened, and what didn’t happen, in and around JHS 271 was a major determinant, however, of decisions that would shape urban education for the next generation” (pg. 157).

One of the challenges in reading Inside Ocean Hill-Brownsville is following the story’s complex list of characters woven throughout Isaacs’ narrative. The text would benefit from the use of a diagram to map the intricate relationships between politicians, union leadership, school leadership, teachers, students, district board members, school board members, journalists and community activists- all of whom played prominent roles in the events.

The power of the story is that Isaacs offers not just a firsthand account of life inside the classroom walls at JHS 271, he also provides valuable insight for those preparing to teach or currently teaching in urban public schools. The notion of the teacher as a welcome guest who honors the contributions of a hardworking community is formative to Isaacs’ thinking in his early days as a teacher. This mindset both distinguishes Isaacs and others who chose to cross the picket line also in spite of the ire of UFT leadership. Unlike the depictions of others who have told the stories of Ocean Hill-Brownsville, Isaacs highlights the important work that was taking place within classrooms; innovations that included the creation of African-American Studies and incorporating cultural artifacts such as music into classroom lessons in order to deeply engage students in their learning. Isaacs explained, “Our successes stemmed more from the enthusiasm of the teachers, and the respect we showed our students” (pg. 124). The experience of incorporating elements of students’ lives into the classroom to serve as the building blocks for academics stemmed from Isaacs observations of teachers he saw as effective in the classroom. Isaacs explains that to be effective white teachers in a black school, an understanding and respect of African American culture is essential. Among the interesting lessons for urban teachers is Isaacs’ retelling of a student survey project which leads not only to a subversive lesson in statistical mathematics for students, but also a student-generated list of six characteristics that successful teachers should possess: “Energy, enthusiasm, expectations, subject mastery, ability to communicate, and respect for students/families/cultures” (pg.294). Interestingly, these characteristics, brainstormed some forty years ago by Isaacs’ middle-schoolers, mirrors those expected of today’s teachers and found in the most prominent teacher evaluation rubrics. In addition to the qualities of the teachers working in underserved communities, Isaacs’ story also underscores the importance of effective school leadership. He writes, “There have always been some superlative schools, even school districts, in New York’s communities of color, their most common denominator being the skills and vision of their leadership” (pg. 292).

Isaacs concludes with an extensive analysis of the consequences of the Ocean Hill-Brownsville battle for community control. He draws attention to educational practices that serve to severely limit the possibilities for students in black and Latino neighborhoods; including the evolution of an obsessive testing culture that disregards real learning, rampant school closings in black and Latino neighborhoods and the extended school-to-prison pipeline for poor students – all of which are practices that urban communities to this very day continue to struggle against.

Inside Ocean Hill-Brownsville is in part a tribute to the parents, community activists, teachers, and especially the students of JHS 271Ocean Hill-Brownsville. Isaacs honors their perseverance despite their roles as pawns in a battle of dueling political agendas for power and control. The topic of school control is fractious because it relates to accountability as well as directing budget initiatives. Community control provides a platform for engagement in meeting the needs of a community and its children. Despite the environment outside JHS 271, the students and teachers who wanted the community control experiment to have a fair trial shared learning experiences that for Isaacs proved to be the formation of a pedagogy that many urban teachers would benefit from reading, especially those who are guests in our underserved communities.