by Jenna Queenan and Pam Segura

An Introduction, An Invitation

As an abolitionist, I care about two things: relationships and how we address harm.

– Mariame Kaba, We Do This ’Til We Free Us

We invite you to pause. We invite you to think of the work that you do — the work towards liberation, towards healing, towards community. We invite you to hold the relationships that give you life. Breathe them into this reading space; let their tendrils soothe you. We invite you to carry the confusion, the dizzying pain, the aching frustration that comes with this work. We invite you to acknowledge the suffering.

We invite you to pause.

To carry the multiplicity and dynamism of your work — of our work.

This invitation lets you into the heart and spirit of “Radical Visions: Educators as School Abolition,” an Inquiry-to-Action Group (ItAG) that aims to stir the abolitionists within teachers, educators, and organizers. ItAGs are a model of political education designed by and for educators. We have both participated in and facilitated ItAGs over the last ten years through the New York Collective of Radical Educators, where we are also core members.¹ We shape the ethos of the School Abolition ItAG with the following questions: What are trying to abolish? What are we trying to grow?

The School Abolition ItAG — its anchoring questions, its past, present, and future — has taught us that part of abolitionist work is about daily practice. We can commit to this practice by disrupting time as we know it and cultivating complex, nurturing relationships. In this article, we hope to share with you, as someone who is also thinking about the practice of abolition, some of the reflections and questions that have emerged for us after three years of facilitating this ItAG with educators. We start by introducing ourselves and our relationship, then provide some context to school abolition and the ItAG, and finally share some of the key reflections that emerged for us about what abolition as a daily practice, particularly for educators, involves. At the end of each section, we include questions in italics for you to do and move with as you desire. Our hope is that you read this article as an invitation to think about how abolition lives in your daily life and relationships, particularly in the context of school abolition.

Our Friendship

Our friendship is a living text. It stretches across great differences in identities and lived experiences. Yet, it contains many similarities, many connections and synergies. It creates a nuanced sound that breathes life, depth, and color into our political and personal work. It is molded by critical love for self, community, and the world. It is open to divergent perspectives and changing times.

I – Jenna – identify as a White, queer educator. For me, what I remember most from high school and college is less about what I learned in the classroom and more about what I learned through activism and organizing across a variety of issues from queer rights to racial justice to Palestinian solidarity work. While I was one of those kids who liked school – and acknowledge that my privileged identities probably contributed to this love as well as some incredible teachers – movement spaces are where I really got my education. I moved to New York City in 2011 to attend graduate school, getting a masters in teaching secondary social studies and an extension license in TESOL. While I did, and still do, deeply believe in the power and importance of education, I learned further through teaching that schooling and education are often separate. Loving the young people I taught (and who taught me) was important but not enough. The quality and content of my teaching and pedagogy matter(ed) but we – my students and I – still often felt stifled by the institution of school: standardized tests, grades, the constraints of time, the pressure to produce and prove our worth.

I — Pam Segura — am an Afro-Latina who was born and raised in the Bronx. My family comes from the Dominican Republic; histories of survival and struggle continue to shape our story. I am a former public school teacher and current political educator. School has represented a number of things to me: conformity, pain, joy, friendship, healing, rejection, trauma, and connectivity. School abolition — as a framework, everyday practice, political action tool — allows me to uplift the healing pieces of state-sanctioned schools.

We met in 2017 at the Free Minds, Free People Conference in Baltimore, Maryland and through meetings with the New York Collective of Radical Educators (NYCoRE). That fall after we first met, we read adrienne maree brown’s Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds with friends from the NYCoRE community. That reading community allowed us to talk through some complicated realities: the constraints of time and the multiplicity of perspectives in organizing spaces. We eventually read Onward: Cultivating Emotional Resilience in Educators and continued to build a friendship through shared texts and food in coffee shops, bars, parks, and even Jenna’s parent’s apartment.

School abolition entered our conversations in the spring of 2020 when we read Ruha Benjamin’s Race After Technology through a book club organized by the Abolition Science podcast. That summer, as the COVID-19 pandemic continued and the 2020 uprisings unfolded, we began thinking about school abolition together. Over the course of several years, we had been discussing co-facilitating with one another, moving at the speed of trust. “Move at the speed of trust” is a principle of emergent strategy listed in adrienne marie brown’s book, Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds. According to brown’s website (adriennemareebrown.net), Emergent Strategy “is a guidebook for getting in right relationship with change, using our own nature and that of creatures beyond human as our teachers.” The full principle is: “Move at the speed of trust. Focus on critical connections more than critical mass — build the resilience by building the relationships.” Our excitement about working together came in part from a shared appreciation of questions and desire to move beyond binaries. All of these experiences are what brought us to facilitating an Inquiry to Action Group with NYCoRE on school abolition.

Questions to pause: Who can support you around abolition in your life? Why? Are there people who could maybe support you but you aren’t close with at the moment? How can you grow the relationship?²

Framing: Lineages and Definitions

We see ourselves as anchored in “a long tradition of abolitionist education, one particularly rooted in Black feminism and the work of women of color for whom pedagogy and politics are inseparable. This tradition is internationalist and grounded in a radical politics of place. Working in schools, unions, and neighborhood organizations, abolitionist educators make connections that bridge spatial divides and create possibilities for beautiful acts of solidarity across scales small and large.”³

We also acknowledge that this work is deeply rooted in the histories of the abolition of slavery and movements to abolish the prison industrial complex,⁴ which are deeply connected.⁵ School abolition takes its inspiration from these movements, from the work of organizations like Critical Resistance and the Abolition Collective as well as organizers, scholars, and artists like Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Mumia Abu Jamal, Nina Simone, Dylan Rodriguez, Mariame Kaba and so many others. We name these groups and people here not just as citations, but also as an acknowledgement of those we have and are learning from.

In the Radical Visions: Educators as School Abolitionists ItAG, we begin with definitions of abolition as our grounding. Then, we work together to define school abolition, drawing from activist scholars such as Bettina Love and David Stovall as well as Lessons in Liberation: An Abolitionist Toolkit for Educators. The following is a synthesis of the definitions of school abolition we’ve developed collectively over the past three years:

School abolition is a visionary process of tearing down and building up, similar to definitions of abolition. School abolition is abolishing punitive practices in schools that replicate the PIC (such as the fact that school is compulsory) AND in the long term means abolishing the institution of schools (at least in the sense of how schools have been designed, although it doesn’t mean we don’t still have community educational spaces). While educational spaces should teach young people to be accountable for harm they caused, they should use restorative and transformative justice practices rather than punishing students. Ultimately, school abolition means creating educational spaces where everyone can thrive and is not treated as disposable.

We believe that engaging in the work of school abolition requires us to identify the egregious abuse and harm that happens in state-sanctioned school buildings, especially (although not only) public schools that work with and in disenfranchised communities. When we say state-sanctioned schools, we mean compulsory education for grades K-12. We mean schools wherein most people involved — students, parents, teachers, administrators — have less and less agency. In school abolitionist work, we are asked to identify the beautiful, healing practices that are already happening in schools in the midst of the harm. We gather resources we can use in this work, both from within state-sanctioned schools as well as outside state-sanctioned schools. The in-between work on our way to school abolition requires us to simultaneously reduce as much harm as possible in school buildings AND create alternative spaces that radically shift practices in schools. Ultimately, school abolition is a deeply nuanced, multifactorial process. Because there is so much work to do, we need as many of us as possible in this work. It was with this in mind, and an eye and heart toward the in-between work of school abolition, that we approached our facilitation and planning for the ItAG.

Participants in the ItAG, including us, felt a lot of tensions around how to get to school abolition. Some of the questions and contradictions below capture those tensions.

- What are the concrete action steps we can take now to get closer to education for liberation, an educational space where everyone can thrive?

- There was some uncertainty around whether there is anything in the (institution of) schools that we want to recycle. We acknowledged the historical (and current) context of schools as rooted in colonization and assimilation as well as disembodied, ableist ways of learning that separate the body from the mind. Even the structure of many school buildings is oppressive. We also acknowledged that schools as they currently exist haven’t been around for that long: less than 200 years. Even if there is nothing we want to recycle from schools, there are still community/institutional spaces that we can look to as models, such as freedom schools, which were alternative educational spaces for Black children during the Civil Rights Movements of the 1960s.⁶ We also recognized the need to be mindful of our context. Our conversations were (somewhat) specific to schools in the U.S. context. While it can be expanded, there are nuances to attend to that are particular to how schools have been built in the U.S.

- Money: Where does the funding come from? Where should the funding come from? School abolition is connected to the abolition of other harmful systems in our society (including capitalism). We still believe (or at least some of us do) in the idea of public education. We want to be careful that school abolition doesn’t get co-opted by those who want to privatize education.

- Community: How autonomous should communities⁷ be in deciding what happens in educational spaces? Who “runs” the school and for whom?

- The slow work that’s needed: cultural shifts, relationship building, confronting internal biases and fear. We spent time thinking about the unlearning we need to do because we’re “buried” by an idea of what schools “should be” that is rooted in punitive, assimilationist, compulsory practices. We acknowledged the array of emotions in this work, including fear and radical hope.

We want to acknowledge the many people, educators and students (we are all both), who contributed their ideas through the ItAG, including: Martin Urbach, Stephina Fisher, Amy Gutierrez, Alba Lamar, Sarita Covington, Rachel Posner, Juan Córdova, Théa Williams, Denisha Jones, Martina Meijer, Sara Aboobakar, Sara Minsky, Phil Traversa, Céleste Arditi, and others.

Question to pause: As we think about lineage, we want you to consider: Who inspires you in this work, even if they do not identify as an abolitionist? Think about: friends; family – chosen and blood, those who are living and those who are not; comrades; thinkers; artists; organizers.

Framing: The Structure of the ItAG

We facilitated our first ItAG on school abolition online in the winter of 2021. Our primary goal was to help participants define school abolition and think through what that meant for them as educators. We knew that schools were (and are) rooted in punishment and assimilation. What does it mean to be someone who believes in school abolition yet works in schools? How do we hold these tensions? How do we help other educators hold these tensions? We also recognized a need for spaces where people can practice abolition and transformative justice. Therefore, in the initial planning stages, we asked ourselves and each other: What does it mean to create an abolitionist space for educators?

In the first year, we followed the NYCoRE ItAG model, facilitating one session a week for six weeks. Our curriculum covered the following:

Session 1: Our first session focused on building relationships through storytelling and community agreements. This is because we know that abolitionist work is best done in community and we wanted to create a space for participants that felt⁸ abolitionist. Rather than directly asking about general community agreements, we had participants journal and discuss the questions we introduced at the beginning of the article: What do we want to abolish in this space? What are we trying to grow in this space? We also asked participants to explore how they wanted to handle conflict within the ItAG, if and when it arose.

Session 2: Our goal for this session was to root our following conversations and activities in the movements to abolish slavery and the prison industrial complex, as well as considering connections to movements against settler colonialism, so we started with definitions of abolition.⁹ We then moved into racial affinity groups, where we examined what abolitionist work means for us given our racial identities. Racial affinity spaces are important because we believe that engaging in abolition is directly affected by our racial identities. When inviting people to sign up for the ItAG, we decided to ensure that at least 50% of those who signed up identified as people of Color. We did this by advertising through word of mouth, listservs, and our social media platforms. For racial affinity groups, we ultimately divided participants into two groups: people of Color and White people. This was not an easy decision and at one point we considered three groups. At the end of each affinity space throughout the ItAG, we invited representatives from each group to share a lingering idea that emerged from that conversation. Our hope in the sharing was to respect the stories shared in racial affinity groups and nurture healthy conversations across racial groups.

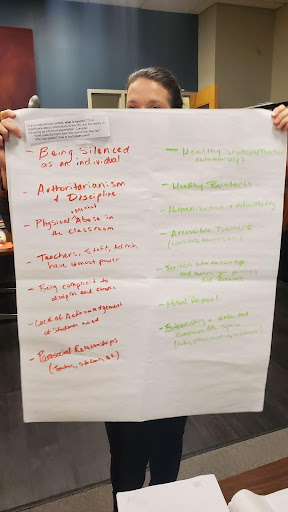

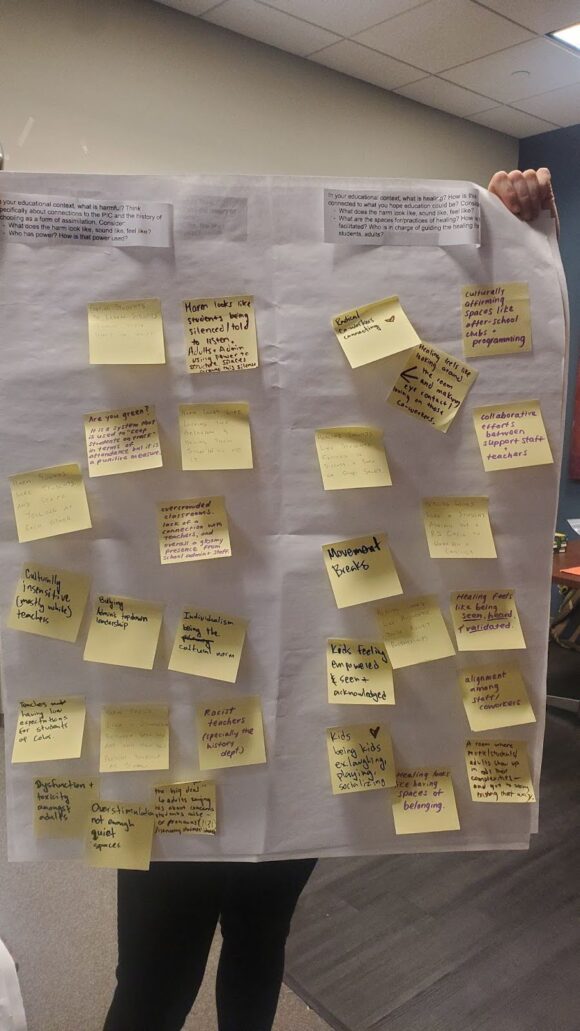

Session 3: In this session, we focused on defining school abolition, both collectively and in institutional affinity groups. In these affinity groups, individuals were placed into either elementary/middle school, high school, and post secondary. We used institutional affinity groups in order to structure a conversation about what is harmful and what is healing in specific educational contexts. Below are some images and synthesized points from our 2023 ItAG.

On the left hand side, people wrote down what they find harmful in schools. On the right hand side, people wrote down things they find healing in schools.

Session 4: We focused here on defining transformative justice and thinking about what transformative justice work can teach us, both in our ItAG community, as well as our practices in schools. We recognize that transformative justice is “a set of practices that happen outside of the state, so this is not something that you can take into schools” but you can “take the values into schools … and those values are around ending prisons and transforming our understanding of accountability and disconnecting the idea of punishment and justice.”¹⁰ We focused our conversations on what we can learn about navigating conflict from transformative justice work, particularly given our racial identities, and used this session as an opportunity to revisit the community agreements we drafted in our first session.

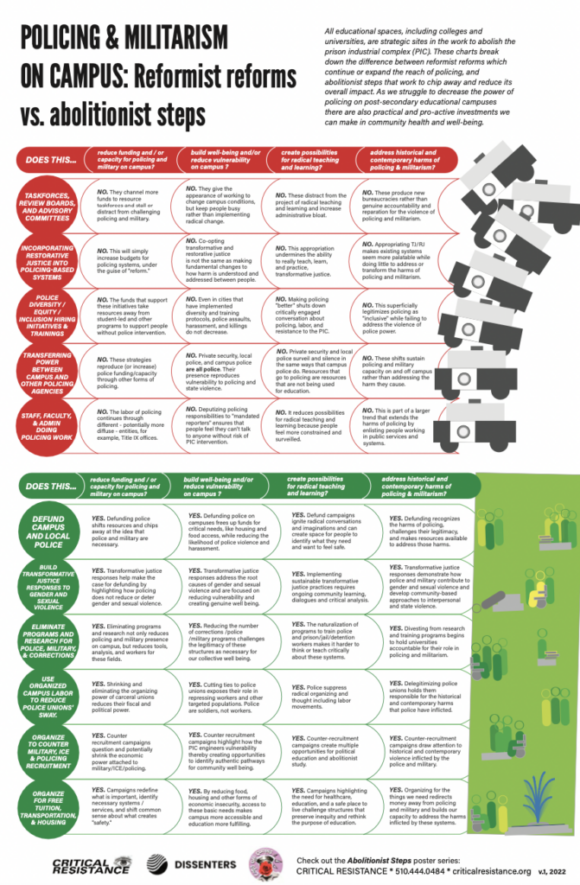

Session 5: As we approached the end of our ItAG time together, we shifted towards thinking about action. In session 5, this meant thinking about the tensions of this work through activities such as vent diagrams.¹¹ We also use the framework of reformist reforms versus abolitionist steps, developed by Critical Resistance, as a way to think about what we should be fighting against and for in our school spaces. Critical Resistance explains in the “Abolish Policing Toolkit” that,

While “reform” simply means a change, reformist refers to a kind of liberal political leaning that maintains the current oppressive system by insisting the system is broken and just needs to be fixed. Claiming the PIC (or any of its tools) is broken supports it continuing to exist. Reformist reforms, or reformist change, are about improving institutions so that they can work better. But when an institution is rooted in oppression historically and is designed to maintain powerlessness and inequity, making that system work better will increase its ability to inflict harm and violence. If the job of a system is racialized social control, then fixing it to do its job better will improve how it carries out racialized social control. The system needs to be completely uprooted and dismantled to end its oppressive power over our lives.

As the examples in the charts below show, abolitionist steps work to reduce the impact of the prison industrial complex and move us closer to abolitionist futures.

Graphics courtesy of Critical Resistance

Session 6: We closed with reflections on our time together, sharing ideas about individual action steps, and freedom dreaming. Together, we imagined what an abolitionist educational space in a fully liberated society might include, with the goal of thinking about what we’re fighting for in the long term.

After the first ItAG, we worked with Lisa and Gwen, two college students who we were connected with at Swarthmore College, to create a resource guide that includes the agendas and materials from each session. This guide is publicly available and we invite you to check it out if you’re interested in learning more about the specific agendas and resources we used. Please note that this guide is now several years old and important resources have come out since its release, including Lessons in Liberation: An Abolitionist Toolkit for Educators. If you end up using it, we would love to hear your feedback! During our second and third years of the ItAG, we included an additional session on embodied abolition, facilitated by Dr. Farima Pour-Khorshid. In 2023, we were in person for the first time and co-facilitated with Juan Córdova, an elementary public school teacher.

Question to pause: If you were going to design a political education series, what would the topic be and how would you facilitate this learning? Consider not only the topic, but the process. Who are the educators, teachers, and/or guides who have shaped your own learning? How can you channel these individuals in your political education work?

Reflections

Relationships Within the ItAG

Relationships are at the center of our ItAG. Through relationships, we co-evolve with the support of people we love and trust. Learning new concepts like school abolition while developing friendships fortifies so many areas of our lives — not just our work towards educational justice, but also our rights to a life filled with meaning, joy, and imagination. Through developing deep relationships, we aim to build trust and create a space where we can imagine alternatives and practice navigating conflict and harm while moving away from punishment.

In the ItAG, we tell folks about the story of our friendship because we feel like it’s important for participants to not only know who their facilitators are but also know a little bit about the relationship we have with one another. We walk them through the different pieces of our friendship that led to the present moment of the ItAG. We call ourselves sisters and claim our sisterhood as an invaluable component of the ItAG. After we present our sisterhood as a guide, we begin to spark new connections, thoughts, wonderings, experiences, and ideas between the ItAG participants, working to develop the trust it takes to be vulnerable with one another, a necessary component of school abolition.

We aim to build trust and encourage vulnerability and introspection in several ways. Nearly every session of the ItAG begins with a question or prompt from the Harvest of Survival: An Affirmation Deck inspired by Octavia Butler, created by the Homegirl Box.¹² This deck of cards is inspired by Octavia Butler’s prophetic visioning in the Parable of the Sower series. The questions and prompts are separated into five distinct categories: innerverse; bend reality; forward; from the ashes; and spirit. The deck invites folks to think about their psychic lives and how those lives are interwoven with and mapped onto many-sized communities. In the world of the ItAG, these many-sized communities include the ItAG itself as well as the classrooms and schools, and other educational spaces, that our participants represent. Of course, participants’ own unique identities, histories, and passions bring other communities into the space as well.

Some of the questions from the Harvest of Survival affirmation deck include:

- How are you home building, world building, and universe building? (category: bend reality)

- What is possible if we release fear? (category: forward)

- What support do you need right now? Ask for it. (category: from the ashes)

- How are you protecting and supporting your life, your people, and your world? (category: spirit)

- How will you create your own paradise amidst chaos? (category: innerverse)

Sometimes, we answer these questions by talking with two or three people. Other times, we answer these questions by drawing together. We use markers, pencils, pens, crayons, stickers, construction paper, glue, and other items to respond; when we were online, we used both online platforms like Jamboard and also invited people to create in their own spaces with what they had available. Our art pieces become a gallery space. There is music playing in the background; participants can enjoy snacks or beverages from our shared food table (when we were in person). In short, the process of answering the Harvest of Survival cards — reflecting individually and privately, talking with new friends, drawing, moving — brings the content of the questions to life. The connections between school abolition and relationship are experienced rather than discussed; the cerebral, in other words, becomes the embodied.

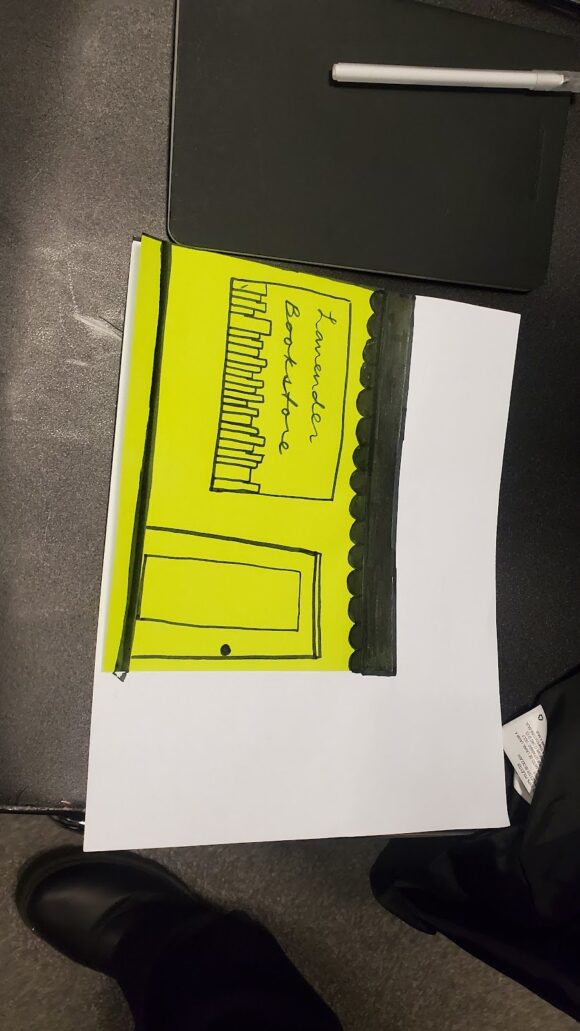

Below, are some of the art created after reflecting on one of the Harvest of Survival prompts.

Other pieces of our facilitation strategies are centered on relationships as well. We co-curate this playlist with our participants. We encourage people to share music that makes them feel good. We do this by asking people to select songs that bring them joy and make them feel free, not songs that they think are “cool.” We also share that, as facilitators, we like genres that are not typically heard in movement spaces. We ask that people come as they are, merging different genres and languages of music. This playlist allows us to move in the ways that we feel comfortable moving. We hear songs from our childhoods; we hear songs that our students love to sing or rap to. Our playlist creates the scaffolds for vulnerability.

We also prioritize facilitator transparency. We name when there are sudden decisions to make about time, a specific activity, or an unfolding discussion. We explain when our own issues around control emerge. This allows us to move away from the myths of expertise, power, and knowledge hoarding. The facilitators do not hold the knowledge; rather, they gather various resources to hold space for people to co-create knowledge. We know we are not perfect and we give ourselves grace by facilitating in a way that allows us to mess up, apologize, and make amends. Part of why we are able to do this is because, from the beginning with community agreements, we establish that conflict and mistakes are expected and are something we are collectively committed to working through.¹³ Relationships, then, emerge from a place of authenticity.

Questions to pause: How do you respond to conflict? How does conflict make you feel? Think about a moment where conflict led to a stronger relationship and a moment when conflict fractured a relationship. What was different? What ways of being are you co-cultivating with your communities to prepare for conflict in the future, so that you can address conflict in ways that do not resort to punishment?

Slowing Down Time

Time has a strange, constrained, and paradoxical presence in state-sanctioned schools. Teachers often spend a significant amount of time delivering instruction; yet, there is not enough time devoted to developing healthy, nurturing relationships, ideas, and experiences with students. Teachers need more time to conceptualize learning goals with their fellow teachers (and ideally, students and families); however, so-called professional development spaces rarely provide time for this and are often planned in a haze of urgency. Students need to develop their emotional, social, and intellectual lives with nuanced, loving teacher guidance, support, and care; teachers, however, need to provide this attention quickly and to anywhere between 30 to 150 students. Teachers, in short, are expected to time travel, living in the present moment while also contending with the past and future of their students’ intricate lives within the school community.

In the midst of this temporal chaos, teachers are also called to respond to the emotional, social, mental, and economic needs of their students’ lives and worlds outside of school. These needs are deeply tied to cultural and historical contexts. Contextualizing students’ lives necessitates time for political education that places their students as well as state-sanctioned schooling within a context.

But there’s just no time, at least not in the ways that schools currently function.

Through the process of facilitating and reflecting on this ItAG, we have identified that teachers are placed in a deeply unethical time bind.¹⁴ We believe that disrupting this time bind is part of the work of school abolition, work that requires relationships and reflection. And so we must slow down time so that educators have the ability to enter the present moment. Once educators are present-minded and present-bodied, we can begin the gradual and beautiful work of theorizing and embodying school abolitionist practices while also recognizing that structural changes are also needed.

In the ItAG, we slowed down time by creating long check-in questions; moments for pause as well as eating and bathroom breaks; and honoring the fact that educators have countless responsibilities in addition to our ItAG. There is no penalty for “showing up late” to a session. Indeed, we are not sure what that means within the context of this ItAG. We make room for thoughts that are emergent, forming through articulation within our beloved community. Participants, in other words, do not need to be experts with clear objectives, standards, mini-lessons, and assessments. Together, we can ask soul questions about the purpose of education. And we understand that these are life questions, not essential or enduring questions that capture three months worth of learning.¹⁵

We also did not rush in our own planning. We met for several hours on Sundays during the ItAG season to plan. We reflected at length about what happened in the previous session; we talked about the joys, woes, and wonders that emerged in our individual and intimate conversations with participants. We read the work of the people we mentioned above and challenged our own assumptions about concepts. We made room for joy and celebration in our planning, including time to check in, even if we didn’t feel like we had the time, because we believe it’s important to acknowledge one another as human beings both in and beyond our work together. By slowing down time for ourselves, we hope that we modeled and gave permission to our participants (and readers) to slow down time as well.

Questions to pause: What is your relationship with and to time? What feels harmful? What feels healing?

Tensions

The work of school abolition surfaces multiple tensions that come from working in an oppressive institution while simultaneously wanting to tear it down and build something new. Oftentimes in our society, living under racial capitalism, we are so steeped in institutions that operate from places of punishment that we believe punishment is supportive for those receiving the punishment (typically, in the case of schools, this is students although it can also include teachers). In schools, logics of punishment show up in so many ways: standardized tests, grades, uniforms, rules regarding behavior and classroom management, etc. We can’t tell you the number of times we’ve heard teachers say something like, “I’m doing x because I need to train students to be “successful” in the world as it is now,” and therefore they need to learn to follow rules, do well on standardized tests, etc. There is a plethora of scholarship and stories around how these logics perpetuate the school/prison nexus,¹⁶ so we won’t get into depth here. What is relevant for our work in the ItAG is that we believe that engaging in the daily practice of abolition requires unlearning the idea that punishment, in the multitude of ways it is perpetuated. Part of school abolition is doing the slow work of “abolishing the cop in our head and hearts.”¹⁷

For many of us, navigating these tensions means spending time sitting with and thinking through how to best live with one foot in the world we currently inhabit and one in the world we are creating. What is our role in school abolition? For some educators in the ItAG, this has meant thinking about whether they are best suited to do the work within state-sanctioned schools or outside of them in alternative educational spaces. We try to create space in the ItAG for both because we recognize that we need people within and without.

Vent diagrams are one tool we used to navigate these tensions and look for ways to live at the intersection of what feels like two opposing sentiments. A vent diagram is “a diagram of the overlap of two statements that appear to be true and appear to be contradictory. We purposely don’t label the overlapping middle…. A good vent draws out a tension that we don’t have language for because that non-binary overlap isn’t really part of our public discourse (yet). By styling these tensions as unlabeled Venn diagrams, we get to a) actively confront binary thinking and b) imagine what’s actually in the overlap every time we see and feel the vent.”¹⁸ Some of the statements that came out of the ItAGs are:

- Questions about school vs education, and how we get to the liberatory education we’re fighting for, such as: I don’t believe that school abolition can happen in schools/universities vs I want to continue working in schools/universities.

- Questions related to burn out and our role as educators, such as: Teaching energizes me vs. Teaching takes away all of my energy.

- Questions about what students need to support their learning, such as: 1) The process from ideation to editing an essay can be meaningful for students to express their thoughts, emotions, and ideas vs. the processes from ideation to editing an essay can be incredibly harmful to students because it values traditional, Western ways of communication (written vs. spoken language) and 2) I need a quiet classroom so that I can make the many decisions I have to make as a teacher vs. I need a classroom with sound because learning is a social experience.

In our community agreements, we name that we are all students of abolition. This means that we will always be learning and we do not expect perfection. We’re all going to mess up in our attempts to teach in more liberatory, life-affirming ways. We are all going to act from a logic of punishment at times. How can we hold ourselves with both care and accountability in this work? How do we identify what we want to abolish and what we want to grow in schools and alternative educational spaces? Our hope is that the community we create in the ItAG can help us do this.

Freedom dreaming in our final session was one way that we imagined what we’re fighting for. Some of the features that came up include: play, intergenerational learning, no grades/standardized tests, shared power, slowing down time, sharing food, prioritizing relationships, different structures/outdoor time, abolishing the police in schools. When thinking about how we can move closer to our freedom dreams, we broadly use the framework of: What are we fighting against? What are we fighting for? What are the abolitionist steps we can take to get us closer to what we are fighting for?

We also want to acknowledge the tensions that arise from our approaches in the ItAG and the limitations of our work. We know that material realities need to be changed, not just individual mindsets. While our focus in the ItAG is on examining our material realities in schools, we do not explicitly organize to change them, beyond supporting individual teachers in thinking about what those changes might be and how they can contribute to change. Many of the people in the ItAG do organize around issues connected to school abolition, but not all. As facilitators of the ItAG, we see ourselves as political educators rather than organizers but also recognize the need for organizing in the movement for school abolition. The questions to pause below are ones with which we constantly grapple.

Questions to pause: What is your role in the work of abolition? What are some of the tensions you feel in your work? We invite you to spend some time making a vent diagram if it feels useful!

Closing

This article documents some of our thinking, moving from our relationship to conceptualizing school abolition to considering how the ItAG model of political education can lead to a praxis of school abolition. Our experiences and conversations about school abolition have led us to think about abolitionist work in the other spaces that we are in.

Pam is currently studying psychology at the New School for Social Research (NSSR). In her clinical and research work, Pam is interested in working on drug use, racial trauma, and Afro-Latinidad. Harm reduction is at the heart of her work at NSSR. Harm reduction also connects her to school abolition work. Some questions she has regarding harm reduction:

- What can harm reduction teach us about ourselves, our daily practices, and our work towards liberation?

- How is harm reduction a step towards liberation, a part of the in-between work?

- What are the connections between harm reduction and transformative justice?

Jenna left the classroom in 2020 to start a PhD in education at the City University of New York. In her/my words: I am constantly sitting with the knowledge that I left one complicated, problematic institution to go into another and have many questions about what this means for me and my work. Here are some of the questions that I’m sitting with at the moment as we close out this article:

- In every institutional space I’m in now, I think about: What do I want to abolish/grow as framing questions.

- What does university abolition mean? I still feel unsure about how I define university abolition. While I believe school abolition means that schools as they currently operate shouldn’t exist, I still imagine community-centered educational spaces in a future society but I’m not sure most components of universities should still exist (ex: research, specialized job training, etc). However, I want to also recognize the long history of organizing that has happened within (but not necessarily because of) university spaces, including my own training in organizing. If university abolition means that universities should not exist at all, then what does that mean for me as I think about working within universities?¹⁹

- More broadly, how are school abolition and university abolition similar? How are they different?

And to close, these are some of the questions we’re thinking about together and with our communities.

Daily questions: Am I (are we) moving away from a punishment/scarcity mindset in my (our) daily actions? How? Where can I (we) grow?

Life-long questions: What are the abolitionist steps I (we) want to be part of making happen? How can I (we) use my (our) skills to contribute to the movement of school abolition and the broader abolitionist²⁰ movement?

Notes

1. NYCoRE and ItAGs have a twenty-plus year history! To learn more about ItAGs and NYCoRE, go to www.nycore.org. Being a core member means we are both in the leadership body of NYCoRE.

As a note, we use footnotes throughout the article as a form of citation, but do not follow standard citational practices. Instead, we see our footnotes as a way to provide you, the reader, with more information: resources we have used and can offer, explanations of our thinking and where our ideas come from, etc.

2. Another activity that might be useful, alongside these questions, is pod-mapping. The concept of pods was developed through transformative justice work. “Your pod is made up of the people that you would call on if violence, harm or abuse happened to you; or the people that you would call on if you wanted support in taking accountability for violence, harm or abuse that you’ve done; or if you witnessed violence or if someone you care about was being violent or being abused.” This quote comes from the Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective. For more on pods, go to their website: https://batjc.wordpress.com/resources/pods-and-pod-mapping-worksheet/ and/or read chapter 11, by Mia Mingus, in Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement.

3. This quote comes from the call for proposals for this journal. Credit goes to Mieasia Edwards and Lucien Baskin for writing such a thoughtful, provocative call!

4. For more information defining the PIC, check out resources from Critical Resistance (CR) https://criticalresistance.org/resources/intro-to-the-prison-industrial-complex-101-workshop/. CR defines the PIC as “the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social, and political problems.”

5. For more on these connections, we recommend starting with Are Prisons Obsolete? by Angela Davis and 13th, directed by Ava DuVernay.

6. For more on freedom schools, we recommend starting with this article and this PBS documentary.

7. We recognize that community is a term often overused and vaguely defined. At the same time, the definition of community is often context-specific and therefore it can be challenging to develop a unilateral definition. In the context of schools, the term community is often made up of those who attend and work at the school, as well as their families and broader networks, although even this definition can be complicated by other factors.

8. This came from a conversation we had when we were first visioning the ItAG. We know how being in an abolitionist space feels but we still struggle to put what this means into words.

9. Here is a link to the definitions of abolition that we put together: bit.ly/abolitiondef. If you have others to add, please let us know by emailing us.

10. The Building Accountable Communities Project, a collaboration between Project Nia and the Barnard Center for Research on Women, put together a series of videos on transformative justice. This quote, shared by Shira Hissan, is from one of those videos, titled “What is Transformative Justice?” To watch the video, go to: https://www.accountablecommunities.org/videos/what-is-transformative-justice

11. For more about vent diagrams, check out chapter 20, “Vent Diagrams as Healing Practice” by Elisabeth Long, in Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement. We will share more on vent diagrams later in the article.

12. You can download a subset of the cards here: bit.ly/harvestcards or buy them at bit.ly/buyharvestcards

13. We want to take some time to distinguish between conflict and abuse here. adrienne marie brown has a really great set of definitions in her book, We Will Not Cancel Us: And Other Dreams of Transformative Justice, on pages 27-30. She defines abuse as “behaviors (physical, emotional, economic, sexual, and many more) intended to gain, exert, and maintain power over another person or in a group. When abuse is present, professional support, space, and boundaries are needed.” She defines conflict as “disagreement, different, or argument between two or more people. Can be personal, political, structural. There may be power differences, and there will most likely be dynamics of privilege and oppression at play. Conflicts can be direct and named, or indirect and felt. Conflicts rooted in genuine differences are rarely resolved quickly and easily. Conflicts can be held in relationship and/or group through naming both the differences and the impact of those differences, facing the roots of the issues, and honest conversation, especially supported conversation such as mediation.” We believe conflict, but not abuse, can be generative.

14. In the spirit of building solidarity and unity across labor sectors, we recognize that this unethical time bind also afflicts other folks who work in service with and for the public, as well as all workers under capitalism. We recognize the time bind that our fellow nurses, social workers, doctors, transit workers, truck drivers, custodial workers, and others face daily. We believe this to be unethical because it dehumanizes workers.

15. For more on how other ItAGs, and similar political education spaces, have met the needs of radical educators, check out the following articles: “Critical Professional Development: Centering the Social Justice Needs of Teachers,” written in 2015 by Rita Kohli, Bree Picower, Antonio Martinez, and Natalia Ortiz; “Nothing About Us Without Us: Teacher-driven Critical Professional Development,” written in 2015 by Bree Picower; and “We Are Victorious: Educator Activism as a Shared Struggle for Human Being,” written in 2018 by Carolina Valdez, Edward Curammeng, Farima Pour-Khorshid, Rita Kohli, Thomas Nikundiwe, Bree Picower, Carla Shalaby & David Stovall. It’s important to note that many of the authors of these articles are members, or connected to, groups like NYCoRE in the Teacher Activist Group Network.

16. The idea of the school/prison nexus emphasizes the similarities between prisons and schools, particularly schools with majority marginalized (poor Black and Brown) student populations. For more on this term, check out scholars such as Erica Meiners and David Stovall.

17. Tourmaline @tourmaliiine. “When we say abolish police. We also mean the cop in your head and in your heart.” Twitter, June 7, 2020. https://twitter.com/tourmaliiine/status/1269774567637213190?lang=en. Tourmaline was not the first to say this however. See also: Rojas, Paula X. “are the cops in our heads and hearts?” In The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex, edited by INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence.

18. This definition comes from E.M./Elana Eisen-Markowitz and Rachel Schragis, who are quoted in “Vent Diagrams as Healing Practice,” the chapter we mentioned above in Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement.

19. Critical Resistance recently put out a new chart specific to abolition on college campuses (within the broader framework of reformist vs. abolitionist reforms) that I’ve found helpful in addressing this question. We linked this chart above. In addition, credit goes to a study group on university abolition facilitated by Conor Tomás Reed in helping develop my thinking around these questions.

20. By broader abolitionist, we specifically mean the movement to abolish the prison industrial complex (PIC).

Notes on Contributors

Jenna (Jennifer) Queenan (she/her) is a White, queer educator and organizer who has been living, teaching, and learning in New York City since 2011. She began working at Sunset Park High School in Brooklyn as an ENL teacher in 2013 and left the DOE in 2020 to begin a PhD in Urban Education at the CUNY Graduate Center. Jenna has been involved in the New York Collective of Radical Educators in various capacities since 2012, before joining the NYCoRE core (leadership) in 2021. She has co-facilitated several Inquiry to Action groups. She also advocated for immigrant rights in NYC schools with the Teach Dream educator team at the New York State Youth Leadership Council, the first undocumented, youth-led organization in New York from 2013 to 2023.

Pam Segura (she/her) is a political educator from New York City. She has also taught as a New York City public school teacher in the Bronx and a community educator in southwest Yonkers. She organize with the New York Collective of Radical Educators.