by Mieasia Edwards and Lucien Baskin

Abolition requires that we change one thing: everything

Does the caged bird sing – or is it wailing as it forces its beak through the cast iron bars that hold it hostage? Visionary clouds cast a shadow over my freedom…your freedom…our freedom. There are interlocking struggles that impact our collective ability to survive and thrive. In this issue, we explore the juxtaposition between liberation and oppression, resilience and resistance, arrestability and freedom, and, how to disrupt dominant power as we look towards our future and our freedom, while reinforcing Black livingness through transformative ruptures. In the Invitation to Collaborate for the issue we wrote, “Theory and action are deeply connected, and therefore we understand collective critical study and radical imagining as central to the work of changing everything. First, we define key terms. Thereafter, we engage the reader in provocation through questions and by postulating ideas on issues such as abolition, freedom and oppression. At the conclusion of this article, the reader is invited to click on key words and phrases for each contributor’s piece covering the myriad of topics raised in this issue.

We define abolition as a dialectical process of dismantling violent and oppressive structures and building new worlds in furtherance of Black livingness where life is precious. Black livingness is the force animating Black geographies. What is Black Geographies? “Black geographies, as a subfield, centers Blackness as a geographic framework to: explore the geographic, social, political, racial, ecological, cultural, and economic processes and spatial patterns that constitute the poetics and materialities of Black life.” Understanding how Black livingness and Black geographies exist in tension to and abundantly beyond the forces of racial capitalism help us envision and create radical possibilities. Within these possibilities are opportunities to coalesce and build geographies of solidarity through the development of internationalist consciousness that sees the interlocking of struggles.

In addition to the aforementioned definition, in this issue abolition is explored in various contexts based on the perspectives of the contributors. As the reader, we encourage you to also bring your perspective on abolition as you journey through this edition and consider the one requirement of abolition – that we change everything. As we change the world we live in together, through artmaking, teaching, organizing, parenting, and other life-affirming practices, we also change our horizons of freedom, transforming our collective consciousness and expanding our ability to imagine radical possibilities.

In this issue, we invite you to think, share, and dream with us, as we build on long and vast historical geographies of abolitionist education and experiment our way toward liberatory horizons and Black livingness. We ask of you: what abolitionist futures do you envision? What abolitionist projects have you learned from or participated in? How can education contribute to struggles for liberation?”

In our invitation to collaborate, we asked a series of questions that explored how abolition and rebellion can take shape in practical ways:

- How do we instigate profound change as we remove borders, with a view from below, while reimagining and creating possibilities for liberation from a space of radical hope, love and possibility?

- How are people attentive to the geographic specificities of Black places in their “work,” as well as the processes of scaling up, be that through the building of social movements, struggles within bureaucratic institutions, theorizing across Black space, or making solidarities across partitions including race, discipline, nation, and urban/rural divides?

- How do we build life-affirming institutions at the same time as we engage in the creative and experimental practice of living life with our hearts and minds stayed on freedom?

- What do histories teach us about education for liberation?

- How does carcerality manifest in systems of schooling, and how can the contradictions present be worked through in order to build abolitionist schools?

- What is abolitionist pedagogy, and what are the pedagogies of Black freedom movements? How can we organize care and study in such a way that ruptures the twin forces of organized violence and organized abandonment?

This issue is rooted in the Black abolitionist placemaking practices so movingly narrated by the late great blues geographer Clyde Woods (1998), who writes in Development Arrested that, “Even though the plantation bloc has successfully disfigured even minor reforms and has buried numerous visionary movements, these defeats do not diminish the ultimate wisdom of these goals, the efforts to attain them, or the monumental victories they have birthed. This rich blues tradition remains as relevant today as it was two centuries ago. It is the only basis upon which to construct democratic, sustainable, and cooperative communities” (pp. 271-272).

Black geography embraces the dialectical tension of rootedness and movement. The geographic double consciousness that defines the experience of diaspora shapes our collective thinking, as do the histories and futures of migration, internationalism, and conviviality, which stretch and enliven liberatory geographies. Stuart Hall, Hazel Carby, and Eqbal Ahmad all wrote about the politics of diasporic thought, as did Edward Said (2000), who wrote that, “While it perhaps seems peculiar to speak of the pleasures of exile, there are some positive things to be said for a few of its conditions. Seeing “the entire world as a foreign land” makes possible originality of vision. Most people are principally aware of one culture, one setting, one home; exiles are aware of at least two, and this plurality of vision gives rise to an awareness of simultaneous dimensions, an awareness that-to borrow a phrase from music-is contrapuntal” (p. 186). We seek to build on the cooperative communities and movements described above while also supporting and cultivating plurality of vision. The acknowledgement of the past and the interconnectedness of abolitionist futures creates a testimony of truth so we can unveil, reconstruct, and trailblaze forward.

As we trailblaze forward, this issue marks and acknowledges key dates important to Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s central idea of Changing Everything. In her lecture, “Change Everything: Racial Capitalism and the Case for Abolition,” Gilmore describes Changing Everything with provocation as she explains the electrifying process of organizing with organized people to change the world. Over the two years that we worked on this issue, we chose a series of meaningful dates in the history of abolitionist struggle as milestones in the writing process, including Juneteenth, Black August, Harriet Tubman’s birthday, Haitian Independence Day, and the 53rd anniversary of the Attica Revolt as sources of possibility and inspiration to nurture our thinking as we collaborated with the contributors and planned for our publishing day. Ultimately, we published on October 3rd, which marks the day that Mary McLeod Bethune opened the Daytona Literary and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls in 1904 known for its quality academics exceptional instruction modeling the hopes and dreams we have for the radical possibilities of abolitionist education that can take shape and form at CUNY and in many life-affirming institutions.

We cited those whose work we were building upon in the invitation, rooting ourselves in a long tradition of abolitionists that includes bell hooks, James Baldwin, Nina Simone, Mariame Kaba, Walter Rodney, Bobby Wilson, Katherine McKittrick, Clyde Woods, and Ruth Wilson Gilmore. In the issue, the contributors bring everyone from the PAIGC and Cooperation Jackson to youth in Seattle and elders in West Philly into the conversation as we use reciprocating saws – with cast iron blades – to grind away at the cast iron bars – that attempt to mute the sounds of the caged birds that can soar.

The works in this issue collectively rehearse more liberatory futures in a diversity of forms. Contributors to the issue use poetry, prose, organizing, conversation, zines, teaching, (auto)ethnography, visual art and more to practice life lived differently. As engaged scholars, artists, teachers, and organizers, we seek to understand the world as it has been historically produced in this conjuncture–including through the most violent systems, structures, practices, institutions, and ideologies–in order to make it otherwise; the point is to change the world (Marx & Engels, 1938, Trotz, 2020). Because “liberation under oppression is unthinkable by design,” we view this freedom dreaming as a radical jailbreak of the imagination and foundational abolitionist practice (Meiners, 2016, Kelley, 2002). Engaged in an artistic practice of freedom dreaming, Chris Colon, an artist and student in the Urban Education program, writes that, “Visual practices became a vessel of hope for me. These practices can help folks imagine new possibilities and open nuanced conversations that can lead to world building…I brought my lifelong project of uplifting stories and practices like my mother’s camera use to record our history when society tried to silence us.”¹ The contributors to this issue use a variety of methods to make sense of the world, teaching us to see differently in the process. The transdisciplinary radical possibilities shared by contributors lead us to a deeper understanding that intentional change is necessary, possible, and produced through the collective protagonistic praxis of study and struggle.

In Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California, Gilmore (2007) writes that, “in scholarly research, answers are only as good as the further questions they provoke, while for activists, answers are as good as the tactics they make possible” (p. 27). The contributions to this issue provide an abundance of answers to the questions we posed, and it is our hope that these answers will allow you to ask new questions, use different tactics, and further the work and practice of abolition as we sustain and maintain the movement intergenerationally.

We first dreamed this issue into being in the classroom of Ruth Wilson Gilmore at the CUNY Graduate Center, first in a co-taught seminar with Katherine McKittrick on Abolition Geography and then in a course on Internationalism from Below taught alongside Shellyne Rodriguez. Professor Gilmore’s classes taught us how to see differently, work and think collectively, and ask questions that opened new worlds of possibility. In Ruthie’s classroom, life is precious. In Professor Gilmore’s classroom, abolition is presence and emancipation in rehearsal. In Professor Gilmore’s classroom, we learn that FREEDOM IS A PLACE.

Ruth Wilson Gilmore dedicated her collection of essays, Abolition Geography, “for all of the teachers.” We dedicate this issue to Professor Gilmore, our teacher and the teacher for so many people engaged in the struggle to change everything.

“My dear sista comrade Ruthie walks the walk and models what it means to be an ancestor in training.

I am lucky to call her a friend.”

– Shellyne Rodriguez Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s Syllabus in Rehearsal by Shellyne Rodriguez

Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s Syllabus in Rehearsal by Shellyne Rodriguez

Abolition as Presence and Emancipation in Rehearsal

Because abolition requires that we change everything, abolition is presence and emancipation in Rehearsal. Engaging in abolitionist practices means building not destroying, collaborating not breaking apart, and it is a process of making…together. As Professor Gilmore states:

“One way I’ve been thinking about abolition lately is as emancipation in rehearsal. People act on their own emancipation and then do it again, and they do it a little differently. They do it with other people. Other people might watch and notice what they’re doing, and might join in. There’s this constant unfolding emancipation in rehearsal that frequently but does not always become a huge change in people’s consciousness and way of life. Building from there, and understanding abolition – for many other people, not just me – an understanding that in order to achieve abolition we only have to change one thing, which is everything. But that doesn’t mean erase everything, that doesn’t mean burn everything down. It means wherever you’re at, whatever you’re doing, whatever bites into your existence, by working the energy that you, that I, that we, and others bring together to remedy that problem is part of changing everything. So all aspects of the social reality are part of what has to change” (Gilmore et. al., 2024).

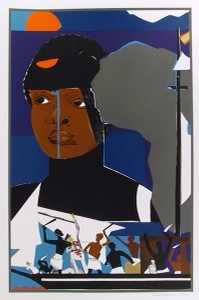

Remedies to problems as a part of changing everything exists in many forms, including abolition and rebellion. Rebellion is a key tenet to Black livingness, as Dina Georgis (2021) wrote in her review of Dear Science, “It takes a rebellious method to know black life, or black “livingness,” as she [Katherine McKittrick] puts it, and a rebellious method to make a relationship to it.” The authors in this issue explore the concept of rebellion in a plethora of different ways, including from slave ships, through abolition feminism, curricular pedagogical refusal, environmental justice, labor organizing, violence intervention and prevention strategies, and oral memory preservation. In Bearden’s Slave Ship collage, imaging and patchwork quilts capture many of the themes in this edition.

Slave Ship by Romare Bearden

The rebellious practices of enslaved and incarcerated people fighting for freedom drive forward our understanding of abolition as emancipation in rehearsal. Rebellion has existed in many forms, like the enslaved people struggling for freedom in Bearden’s Slave Ship and m. nourbeSe philip’s Zong!: As told to the author by Setaey Adamu Boateng, and in people incarcerated at Attica who fought for their freedom. Abolition is most clearly practiced and theorized in this long lineage of rebellion against the most oppressive forms of unfreedom from chattel slavery to incarceration and policing.

Political prisoner Stevie Wilson speaks of “the imprisoned Black radical tradition” to root our understanding of abolition in this lineage (Burton, 2023, p. 13). In Tip of the Spear: Black Radicalism, Prison Repression, and the Long Attica Revolt, Orisanmi Burton (2023) argues that the Attica rebels built an abolition geography within the walls of the prison. The commune the Attica rebels built on D yard was “an infrastructure of collective self-creation” where they practiced mutual aid—meeting each other’s immediate needs within the context of asymmetrical war—and modeled “political forms that would be needed in the future” (p. 91).

Burton (2023) writes that, “By collectively liberating themselves from a domestic warzone and employing collective praxis to create an abolition geography, they constructed an illicit freedom that was more total than that which liberalism allowed even in the so-called ‘free world,’ not only because theirs was not premised on capital, property, and slavery, but also because they fashioned it on their own” (p. 107).

The existence of an abolition geography within the most repressive institution of organized violence is deeply contradictory. While the state attempted to suppress this contradiction through extreme deadly force, the heavily armed police could only crush one physical manifestation of the Long Attica Revolt. Burton (2023) makes this argument brilliantly when he writes in the present tense that “Attica Is,” thus framing Attica to be an abolition geography that extends far beyond the prison walls (p. 230). From the critical work of organizations to free political prisoners such as Jericho and Samidoun, to campaigns against prisons and jails in Kentucky, California and New York, to the Free Alabama Movement and campaign to free the Mississippi Five, the Attica rebellion lives on; a luta continua!

In this issue, we channel rebellion and action as we counter the prevailing dominant forces that work so hard to strip away freedom and keep birds caged.

United States of Attica by Faith Ringgold

University Abolition

As scholars working in the field of education and studying in a public university, we understand this institution to be a site of abolitionist struggle. Abolition in the university must look to the rebellious praxis developed by abolitionists from the Amistad Rebellion and the Haitian revolution to the August Rebellion at the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for Women and the Pelican Bay hunger strike. Universities are what Christina Heatherton (2022) calls convergence spaces, “contradictory socio-spatial sites wherein people from different backgrounds and different radical traditions have been forced together and have subsequently produced new articulations of struggle” (p. 18). These struggles are built on understandings of mutual dependence–solidarity–that link struggles across borders (geographic and otherwise) and see liberation as a collective project. As diasporic places, struggles at the City University of New York (CUNY) and in Harlem have long understood Black, Palestinian, Jewish, and Lenape liberation as inseparable.

Conor Tomás Reed (2023) builds on Heatherton’s argument, writing that “Strategically, schools are among those seed institutions most fruitful to collectively claim. Rhythmically consistent semester by semester, they serve as ‘convergence spaces’ for critical thought and action, allowing us to learn how to push and grow through mass direct democratic participation” (p. 13). The City College of New York is one such convergence space where people have collectively forged new articulations of abolitionist presence. Rooted in Harlem’s long tradition of Black left internationalism, students occupied the campus in 1969, issuing five demands for the remaking of the apartheid university into a decolonized institution. Five and a half decades later students, staff, alumni, and community members once again occupied the City College campus, continuing the unfinished business of making the abolition university. Students and community members at the CUNY Gaza Solidarity Encampment hosted shabbat dinners, union assemblies, and teach-ins on anti-colonial struggles against genocide from the Congo and Haiti to Sudan and the Weelaunee Forest.

The CUNY Gaza Solidarity grounded itself in the history of organizing at City College and in Harlem by similarly creating five demands of their own:

- Disclose & Divest: CUNY’s immediate and total divestment from companies which aid in zionist colonization and war crimes. Ensure accountability by publishing annual reports of CUNY’s investments and contracts.

- Academic Boycott: Ban all academic trips to “israel” (occupied Palestine) and relationships with “israeli” universities, encompassing birthright, Fulbright, and prospective trips.

- Solidarity with the Palestine liberation struggle: Protect CUNY Students & Workers for expressing solidarity with the Palestine Liberation Struggle.

- Demilitarize CUNY, Demilitarize Harlem: Get IOF and NYPD officers off all CUNY campuses and end all collaboration, training and recruitment by imperialist institutions, including the CIA, Homeland Security and ROTC. Remove all symbols of US imperialism from our campuses: Rename the Colin Powell School of Global and Civic Leadership at CCNY and reinstate The Guillermo Morales and Assata Shakur Community and Student Center!

- A People’s CUNY: CUNY was free and fully funded for over 125 years. There is plenty of wealth in New York that could be taxed and redirected to make CUNY fully open and free for all. We demand that CUNY provide comprehensive support for students including Metrocards, housing, food, healthcare, and mental health counseling. CUNY was free while its students were mostly of European descent. In 1969, a wave of campus occupations led to Open Admissions, which allowed all graduating NYC high school students to enter CUNY for free. CUNY started charging tuition in 1976, after the student body became majority Black, Latinx, and Asian. We stand firmly against all tuition and fee increases, as well as against racist and classist standardized admissions testing, which disproportionately harm low-income working-class students of color. We also support and will use our power to fight for the full funding of other city services including K-12 education, public transportation, public housing, and public health services. We demand that CUNY have its tuition free status restored to make education accessible for everyone. We demand that the CUNY admin meets all the demands for a fair contract made by the Professional Staff Congress (PSC CUNY).

Occupations of City College in 1969 and 2024, images courtesy of City College Archives (left) and Luigi Morris (right)

We are honored to be passing the torch to a group of students who will be editing the next issue of TRAUE on the topic of Palestinian liberation. May your diligent scholarship not only illuminate the policing of students from Harlem to Jenin and the scholasticide of libraries, schools, and universities in Gaza, but also the intergenerational practices of oral history forged in the face of settler colonial dispossession, the knowledge of the olive trees, and the pedagogies of solidarity that students made in the encampments.

Freedom is a Place – Where Life is Precious, Life is Precious

Ruth Wilson Gilmore — “Where life is precious, life is precious.”

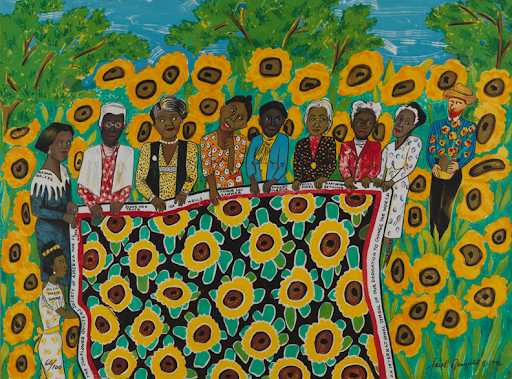

Although the violence that permeates the system and the world as it exists is woven together like a deleterious quilt, quilts also represent unity, solidarity, and the power of community. In this issue we envision a quilt that lifts up interlocking struggles to create radical possibilities as we wrap ourselves in the ancestral warmth and strength that survival demands and create a brighter future filled with daisy-like new beginnings – a rebirth and a new day. We are all well, when we are ALL well. We are all unwell, until, where life is precious, life is precious.

Black Livingness is not a concept, rather a commitment to the existence, evolution and the prosperity of Black people recognizing the interdependence of connected struggles between groups of people based on social constructs like race, gender, religion, class and place. In this issue we explore how the racial, social, cultural and discursive constructions of power interact to perpetuate plagues like Black enslavement, Native American and Palestinian genocide, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, gender discrimination, and LGBTQI+ discrimination – all of which reveal intertwined anticolonial and liberation struggles woven together like a quilt to create a system that must be dismantled, and a place that must continue to be reimagined and changed.

In the piece below, author, quilter, and printmaker Faith Ringgold brings together multiple artistic traditions in The Sunflower Quilting Bee at Arles, putting the post-impressionism of Vincent Van Gogh in conversation with the quilting of Black women in the South. By putting Van Gogh in the print alongside a long lineage of Black (proto)feminist activists: Madam Walker, Sojourner Truth, ida B. Wells, Fannie Lou Hamer, Harriet Tubman, Rosa Parks, Mary McLeod Bethune, Ella Baker, and Willia Marie Simone (who Ringgold freedom-dreamed onto the page), Ringgold connects art and politics while envisioning the possibilities for solidarity through difference.

The Sunflower Quilting Bee at Arles by Faith Ringgold

The Sunflower Quilting Bee at Arles by Faith Ringgold

Like the caged bird that sings or wails, and is able to thrive in all conditions, daisies can grow in many different types of conditions and in almost all climates. They are resilient and engage in what some describe as a rebirth – they close at night and reopen in the morning symbolizing a new day on the horizon. Daisies are also two flowers in one, also known as composite flowers, the outside flowers, petals also called rays, are one flower, and the central disc is another. The two flowers appear as, and grow together as one. Daisies are a representation of twoness, like the double consciousness that exists when we seek to unveil domination and see the world differently through the practice of making it together.

In this issue, we explore how we can build bridges, make connections and engage in decision-making from the ground up to help transform places and make space for livingness. We also realize the importance of engaging in abolitionist practices across borders. Abolition is an internationalist project. Abolitionists work together, from many different places, to change everything, as such our politics must be internationalist. This is not simply the case because the forces we are struggling against, such as climate change, imperialism, and gendered racial capitalism, are global in scale, but also because we strive to build a borderless world where people move freely and create convivial politics from below. As Professor Gilmore writes,

“Abolition has to be “green.” It has to take seriously the problem of environmental harm, environmental racism, and environmental degradation. To be “green” it has to be “red.” It has to figure out ways to generalize the resources needed for well-being for the most vulnerable people in our community, which then will extend to all people. And to do that, to be “green” and “red,” it has to be international. It has to stretch across borders so that we can consolidate our strength, our experience, and our vision for a better world” (2022).

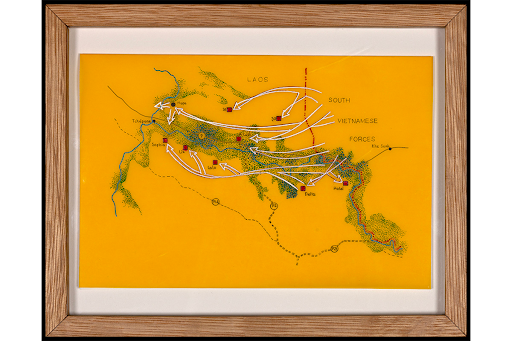

The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture by Jacob Lawrence

The Life of Toussaint l’Ouverture is a remarkable series of fifteen prints by the communist artist Jacob Lawrence, whose work depicts histories of Black liberation and working class struggle. In this biographical sketch of the Haitian revolutionary’s life, Lawrence examines the dialectic that the imprisoned communist Antonio Gramsci (1973) describes as the war of position and war of maneuver. Two of the prints in the series, “Strategy” and “To Preserve their Freedom” illuminate this dialectic. It is the careful, rigorous, militant planning depicted in “Strategy” that makes anti-colonial armed struggle possible. In this sense, the revolutionary planning of the Black Jacobins that Lawrence illustrates so evocatively is reminiscent of the militant education of the PAIGC and Amilcar Cabral’s insistence on understanding the always-changing terrain of struggle, as well as the cartographies of struggle that Tiffany Chung allows us to see differently in her stunning re-mapping of the Vietnamese struggle against French and US imperialism. Tiffany Chung visualizes Gilmore’s notion of abolition as a green, red, and internationalist practice in her maps of Vietnamese liberation struggle, rehearsing emancipation as she demonstrates that freedom is always in motion.

Operation Lam Son 719 in 1971 by Tiffany Chung

Again we ask, what abolitionist futures do you envision? What abolitionist projects have you learned from or participated in? How can education contribute to struggles for liberation? Do we want to be free?

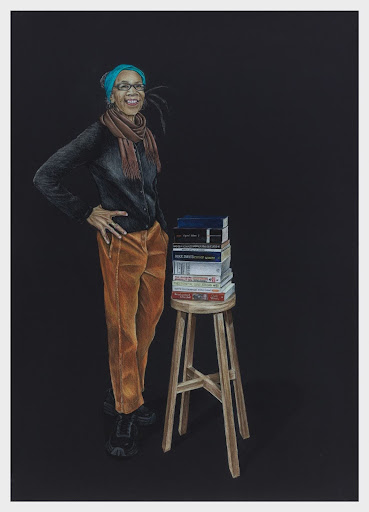

James Baldwin by Leonard Baskin

“Freedom is not something that anybody can be given; freedom is something people take and people are as free as they want to be.” – James Baldwin

We want to be free.

In our introduction, we opened with an invitation to think, share, and dream with us, as we build on long and vast historical geographies of abolitionist education and experiment our way toward liberatory horizons. We thank you for accepting the invitation to undertake this journey toward liberation, making the road by walking together. We hope that you will read the work in this issue generously and seriously, think with the authors, ask questions of them, debate with them, and stretch their ideas to provide insight into the context in which you are working. We believe that the work collected in this issue will sharpen our collective analysis as we struggle to make abolition where we are. Embracing an internationalist imperative, we are delighted that a collective of students will be editing the next issue of Theory, Research, and Action in Urban Education on the topic of Palestinian liberation. We thank the next collective of editors for carrying this work forward.

We thank all of the contributors for trusting us to steward their work in this issue. The contributors are Alia Russell, Jordan Bell, Shani Buggs, Erin Miles Cloud, Atasi Das, Mia Karisa Dawson, Adrian Edmundson, Ayla Gelsinger, Kaleb Germinaro, Kelly X. Hui, Asia S. Ivey, Brian Jones, Shawn Koyano, Samhitha Krishnan, David A. Maldonado, Edwin Mayorga, Erica R. Meiners, Alexis Nicole Neely, Charlie Overton, Shannon Perez-Darby, Darius Phelps, Sophie Plotkin, Jenna Queenan, Neomi Rao, Conor ‘Coco’ Tomás Reed, Travis Richards, Robert P. Robinson, Christopher R. Rogers, Pam Segura, Kushya Sugarman, Cynthia Tobar, Charity Hope Tolliver, Van, Jasmine Wali, Gabrielle Warren, Cinnamon Williams, Imani Wilson, and Karen Zaino.

We acknowledge the energy, time, and dedication of the reviewers for this issue and are immensely grateful for the care and intentionality with which you approached this role. The reviewers were Justin Beauchamp, LeConté Dill, Kavin Edwards, Halle Gordon, Dinorah Hudson, Vani Kannan, Noelle Mapes, Erica R. Meiners, Margarida Nogueira, J.T. Roane, Robert P. Robinson, Jah Elyse Sayers, August Smith, Shreya Sunderram, Yalile Suriel, Mariatere Tapias, and Grace Watkins. Immense gratitude to the previous editors of TRAUE, Jordan Bell and Karen Zaino, for sharing their time, wisdom, and experience with us.

Sonia Vaz Borges and Shellyne Rodriguez met with us early in the process of envisioning this issue and guided us in giving it shape; we are so grateful for your mentorship. Shellyne, as well as Chris Colon, shared their art with us, allowing their abolitionist brilliance to add incredible depth to this introduction alongside the powerful imagery of Leonard Baskin, Romare Bearden, Tiffany Chung, Jacob Lawrence, Luigi Morris, and Faith Ringgold.

Ruth Wilson Gilmore is a renowned organizer, scholar, and exceptional professor, whose commitment to teaching has made our work and that of countless other militant scholars possible. Thank you, Ruthie, for changing one thing in our lives: everything.

As a map to facilitate the reader’s experience, as mentioned above, please find below key words and phrases linked with the contributors’ articles as we pay homage to Zong! and lift up central tenets to the pieces herein.

⛓⛓

maintaining the movement intergenerationally

⅁ sanctuary 🏘

anticolonial struggles ⇏ ⇍ liberation struggles

violence permeates institutions 🔝↓

⇆⇆⇆⇆⇆⇆⇆⇆⇆⇆⇆⇆⇆⇆⇆⇆

curricular and pedagogic refusal

dominant power disrupts ↸ plague 🌪

black livingness ⚫ through transformative ruptures ↺

Notes on Editors

Lucien Baskin is a doctoral candidate in Urban Education at the CUNY Graduate Center researching abolition, social movements, and the university. He is writing a dissertation on organizing at CUNY, as well as collaborative projects on Black radical education in the United States and Britain. Lucien’s writing has been published in outlets such as Truthout, Society & Space, The Abusable Past, and Mondoweiss. Currently, they serve as co-chair of the American Studies Association Critical Prison Studies Caucus, and work as a media and publicity fellow at Conversations in Black Freedom Studies at the Schomburg Center. Lucien organizes with CUNY for Palestine and is a (strike-ready!) rank-and-file member of the Professional Staff Congress.

Mieasia Edwards is a Harlem, NY native committed to creating sustainable, systemic and equitable change through research, action, strategic-planning and policy. Mieasia is a transdisciplinary scholar focused on interlocking struggles and transformative ruptures leveraging abolitionist approaches. She co-authored “Building Consensus during Racially Divisive Times: Parents Speak Out about the Twin Pandemics of COVID-19 and Systemic Racism” published in Social Sciences, and she is writing her dissertation on Black Girl Entelechy. Mieasia began her journey to advance equity as a New York City (NYC) public school teacher and thereafter led two elementary schools as principal. She is presently a Chief Executive in NYC Public Schools where she serves 1100+ schools and more than 270,000 students and families across New York. Mieasia is a public speaker and trained educator committed to collaborating with diverse scholars in furtherance of transformation and justice.

References

Baldwin, J. (1961). Nobody knows my name : more notes of a native son. The Dial Press.

Georgis, D. (2021, September 27). Dear Katherine. Society and Space. https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/dear-katherine

Gilmore, R. W. (2007). Golden gulag : prisons, surplus, crisis, and opposition in globalizing California. University of California Press.

Gilmore, R.W.; Antipon, L.C.; Alves, C.N.; Novo, M.F. Ruth Wilson Gilmore – Freedom is a place. Ruth Wilson Gilmore and Abolition Geography. Geousp, v. 28, n. 1, e-222824,jan./apr. 2024. ISSN 2179-0892. Available at: https://www.revistas.usp.br/geousp/article/view/222824.doi:https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2179-0892.geousp.2024.222824.en.

Gramsci, A., & Hoare, Q. (1973). Selections from the prison notebooks of Antonio Gramsci (G. Nowell-Smith, Ed.; First edition.). International Publishers.

Heatherton, C. (2022). Arise! : global radicalism in the era of the Mexican Revolution. University of California Press.

Kelley, R. D. G. (2002). Freedom dreams : the Black radical imagination (1st electronic ed.). Beacon Press.

Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1938). The German ideology, parts I & III (R. Pascal, Ed.; W. Lough & C. P. Magill, Trans.). Lawrence & Wishart.

Meiners, E. R. (2016). For the children? : protecting innocence in a carceral state. University of Minnesota Press.

Reed, C. T. (2023). New York Liberation School : study and movement for the People’s University. Common Notions.

Said, E. W. (2000). Reflections on exile and other essays. Harvard University Press.