by Charles Overton

The liberation struggle against colonialism, if it is to be a total liberation struggle, is not only for the political conquest of territory (‘flag independence’); it is a struggle to liberate the people from the tentacles of colonialism. The liberation struggle is a social and political phenomenon that gains strength when colonised people organise themselves to reclaim their political and economic sovereignty and to dismantle and destroy the institutions that overpower their own sense of themselves and their capacity to control the fruits of their labour.

– Sónia Vaz Borges, 2022

Abstract

Many disaster risk reduction (DRR) scholars have argued for decades that disasters present a window of opportunity for greater societal transformation. They highlight the ways in which legacies of colonialism still produce vulnerabilities to natural hazards like hurricanes, floods, droughts, etc. However, there still seems to be many obstacles preventing equitable and just recovery efforts to succeed in the wake of growing adverse effects of climate change. The increased severity and frequency of disasters being one of them. To further understanding of how to best take advantage of this window of opportunity this article presents a framework based on literature detailing decolonial liberation struggles and transnational social movements. Specifically, this paper argues that the field of disaster risk reduction could benefit from integrating techniques used by Amílcar Cabral and the PAIGC ‘s militant education program in Guinea Bissau, the institutional foundations of Cooperation Jackson in Mississippi, and the use of formal and informal international spaces by transnational movements like La Via Campesina (LVC) and the International Indigenous Peoples’ Forum on Climate Change (IIPFCC) to address deep rooted structures which produce unequal vulnerability across the disaster space. The mobilizing in disaster spaces framework has at its core decolonial education structures, an alternative way of life, and a balance between being bottom-up locally led initiatives with an awareness of the transnational solidarities that can be formed due to the movements of disasters.

Introduction

In a recent New Yorker article, the author, Sarah Stillman, describes the experience of a group of workers who follow climate disasters around the United States to remove debris and deconstruct destroyed buildings and other infrastructure. This growing group of transitory workers, mostly immigrants, are the first ones to help affected communities rebuild. However, like agricultural workers following crops, these transitory disaster recovery workers are massively exploited due to their vulnerable immigration statuses and an unregulated industry of disaster recovery (Stillman, 2021). Despite seemingly having the altruistic aim of helping communities rebuild, these corporations still follow the core capitalistic model and rely on the exploitation of the labour force to maximize profits (Harvey, 2019). To demand better treatment a growing number of workers have begun organizing with the help of a non-profit called Resilience Force (Stillman, 2021). The article details how Resilience Force has taken these disaster recovery companies to court and won cases for the unjust treatment of these workers.

This another example of labour organizing to demand better treatment in an economic system that relies on exploitation of labor and natural resources to produce the greatest amount of profit (Harvey, 2017). Despite operating in the disaster space, theories on climate change, development paradigms, equity, and justice do not feature in the article. This isn’t to say that the ultimate aim of these labourers and Resilience Force’s isn’t to transform the political economic system. It may be. However, the struggle of Resilience Force and these workers raises some questions. What benefits could be gained by merging on the ground techniques used by liberation struggles and theories on disasters? Could this merger form alliances and solidarities that take greater strides in addressing systemic injustices? What would it look like to mobilize around the risk of disasters in spaces vulnerable to natural hazards and the adverse effects of climate change? Specifically, in this paper I ask what can DRR scholars and practitioners learn from decolonial liberation movements who mobilized people and, in some cases, continue to mobilize around exposing hidden structural injustices? In many cases hidden structural injustices which decolonial movements sought to address still exist in disaster prone areas to produce social, economic, and environmental vulnerabilities unevenly (Fraser et al., 2020). That is why many scholars who focus on disasters and climate change now follow Neil Smith’s notion put forth following Hurricane Katrina that there are “no such thing as natural disasters” (Smith, 2006). Instead, as I will now show, disasters are the result of human decisions which produce unjust social inequalities so that marginalized groups are more vulnerable to disasters and have more difficulty recovering (Reid, 2013).

Decolonial Disaster Centred Mobilizing

In this paper, I attempt to combine theory that disasters are opportunities for progressive changes that produce greater equity and justice with literature on decolonial liberation struggles and transnational movements. Focusing on the risk of a disaster could produce greater solidarities by including all those affected by disasters which span across space and time, and do not adhere to man-made borders. Notably, adopting techniques used by decolonial liberation struggles and transnational movements regarding how they mobilize people to dismantle unjust societal structures could open up new possibilities for DRR practitioners to address the hidden deep-rooted structures that produce vulnerability to climate change and resulting disasters.

Disasters are often cited in the literature as an opportunity for change and transformation (Friedman et al., 2018; Birkmann et al., 2010; Pelling, 2011). However, what is considered transformation differs from place to place which often leads to the recovery process being corrupted by those in positions of power who benefit from the status quo and value economic growth over greater well-being (Blythe et al., 2018; Overton, 2020). This process has been termed “disaster capitalism” (Klein, 2008). A clear example of disaster capitalism is the displacement of Barbudans by the Antigua & Barbuda government so that luxury resorts can be built on wetlands which protect Barbudans from sea level rise and hurricanes (Look et al., 2019; Baptiste & Devonish, 2019). Some scholars assert that disaster risk reduction (DRR) and climate change adaptation measures need to be aligned with larger goals of addressing uneven development (Schipper & Pelling, 2006). Others add that adaptation needs to move past technical fixes so that it is placed within larger fights for social justice (Nightingale et al., 2019). Still others contend that there must be an effort to use the energy present following an extreme event to promote learning capacities amongst the most vulnerable to reduce risk and implement equitable and just adaptation pathways forward (Solecki et al., 2016; IPCC, 2022). Overall, these form the foundations of climate resilient development which combines climate change adaptation and mitigation with sustainable development, and is strongly rooted in equity (Schipper et al., 2021; IPCC, 2018). But there is still a need for greater clarity of what these theories actually look like on the ground.

Aligning DRR with larger calls to address uneven development calls for us as scholars to adopt a decolonial approach to disaster studies (Cadag, 2021). The continued structural dependency and outright entanglement in colonial relationships complicate recovery and coordination of aid to affected communities (Moulton & Machado, 2019). Moulton and Machado continue by calling for a decolonial form of resilience and adaptation centered around climate justice that allows for conversations for how vulnerability is produced (ibid). The framing of a disaster should advance beyond focusing solely on a single event to focus on long-term processes. In this framing colonialism can itself be viewed as a disaster (Bonilla, 2020). Because colonialism did not end with the wave of independence movements in the 20th century but transformed into what Cadag calls neo-colonialism which is largely dependent on the “hegemony of knowledge” which values the “expertise” and recommendations of climate scientists over the lived experiences and desires of local people (Cadag, 2021). Even so, climate scientists lack adequate power to sway politicians away from fossil fuel companies who continue to ignore data detailing their catastrophic impact on the habitable future of Earth (Meredith, 2023). Despite highlighting the role that colonialism and capitalist exploitation have in producing climate change and the uneven vulnerabilities to disasters, there has yet to be a meaningful engagement by climate justice scholars with on the ground tactics used by decolonial liberation struggles.

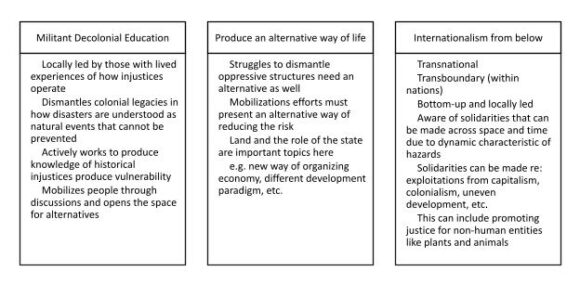

The aim of this paper is to present a possible framework for utilizing the ability of disasters to produce transformative change. The framework has three main components. Firstly, it is important to have a decolonial form of education about the issues that are being addressed. Here, I predominantly rely on Sónia Vaz Borges’s analysis of Amílcar Cabral and the PAIGC’s Militant Education Project that was influential in their success over the Portuguese in the 1960’s and 70’s. It was equally important for the Cabral to produce an alternative way of living while simultaneously dismantling oppressive structures. To further this point, I focus on Cooperation Jackson to illustrate a contemporary example of a decolonial movement presenting an alternative way of life. I discuss two Cooperation Jackson publications, Jackson Rising: The Struggle for Economic Democracy and Black Self-determination in Jackson, Mississippi and What is a Just Transition? and their aim of creating a sustainable solidarity economy in regions heavily influenced by natural hazards and disasters. The third section is titled internationalism from below, which is defined in this paper as bottom-up movements which are transnational and transboundary and actively work to shift institutions of power and injustice that produce uneven development and climate change. To address deep rooted injustices, movements should be locally led by those with concrete lived experiences of unjust structures, while simultaneously taking advantage of transnational solidarities through formal and informal means. In this sense mobilizing in a disaster space must mimic the movements of natural hazards like hurricanes, floods, or droughts, which do not adhere to man-made boundaries or borders, but affect many different places across space and time. In this section I focus on La Via Campesina (LVC) and the International Indigenous Peoples’ Forum on Climate Change (IIPFCC). While admittedly not complete, I believe this framework, once built upon, provides DRR practitioners tools to highlight and address deep rooted structures which prevent climate justice.

Militant Education & Disasters

Whether in Cape Verde or anywhere else in the world, education is the fundamental basis that underpins the work of the emancipation of every human being and the conscientisation of mankind, not in relation to individual or class needs or conveniences, but in relation to the environment in which he lives, to the needs of the community and to the problems of the humanity in general.

– Amílcar Cabral, 1951¹

At the start of their struggle against the colonial oppression of the Portuguese, Cabral and the PAIGC had to solve two main problems. The first was a largely illiterate local population due the systemic disinvestment by the Portuguese in education in Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde. The other was how to mobilize people against a form of colonialism that was less visibly oppressive and violent than in other colonies. The PAIGC found that they could not simply say to the people “don’t you want to overthrow colonialism and imperialism,” and expect them to join the struggle. They had to find ways to connect the struggle for liberation with the lived experiences of the people (Vaz Borges, 2022:13).

To address these obstacles, they held reading sessions where they would discuss the party’s newspaper to distribute their ideas while simultaneously teaching people to read. At these sessions they would also ask attendees direct questions about their lives. Such as, “You are going to work on roadbuilding: who gives you the tools? You are bringing the tools. Who provides your meals? You provide your meals. But who walks on the road? Who has a car? And your daughter who was raped – are you happy about that?” (ibid: 13). These conversations and the broader investment in education contributed to the party’s aim to combat harmful practices not solely through the use of armed conflict against the colonial oppressors. Armed struggle was only to be used when no law will serve to defend or protect the human rights of the people (Cabral, 1980: 252). Thus, violence, while an important part of the cause, was never as the only means of liberation (Bledsoe, 2013). In addition, these sessions solidified people’s consciousness about the struggle, while establishing vital administrative, political, judicial, economic, and social structures in liberated areas. Producing an active alternative way of life in liberated areas while simultaneously dismantling oppressive colonial structures was an important part of the struggle for liberation (Vaz Borges, 2022). The building of “a new political, administrative, economic, social and cultural life” (Cabral, 1980: 268) are equally important as armed struggle. Without producing an alternative way of life, the only thing left in the wake of violence is destruction (Bledsoe, 2013).

Ruth Wilson Gilmore reminds us abolition is not about absence but presence. Abolitionists build new ways of living for the future out of the “fragments and pieces, experiments and possibilities” which exist in the present (Gilmore, 2018). For Cabral, instrumental to producing this alternative way of life was the PAIGC’s Militant Education program. The conceptual and practical application of militant education was deeply influenced by the specific historic moment in which it emerged: the anti-colonial liberation struggle. Its pedagogical role was combined into three aspects: political learning, technical training, and the shaping of individual and collective behaviours. Militant teachers came from the working class (artisans, industry workers, etc.), the peasantry (farmers and rural land-dwellers), as well as a few former teachers and government officials who belonged to the petit bourgeoisie (Vaz Borges, 2022: 22).

These militant teachers had to simultaneously decolonize existing education materials and produce new curricula and materials as part of the PAIGC’s broader educational work. For example, apart from teaching fundamentals such as the alphabet, they also had to critically interpret the message that Portuguese textbooks transmitted and reformulate it in a way that was more relevant to the students’ universe. Therefore, these militant teachers became both pedagogical resource and a mirror of the liberation struggle’s ideals (ibid: 23). The ‘militant’ students, who were both children and young adults, were tasked with sharing what they were learning in these schools with broader communities to gain more supporters for the liberation struggle (ibid: 25).

As Sónia Vaz Borges writes in her book on the importance of the Militant education project to the successes of the liberation struggle:

The PAIGC’s militant or political education was anti-colonial and African-centred in its objectives, aiming to dismantle the biased, hierarchical, and oppressive education system and practices inherited from Portuguese colonial education. It brought new knowledge and experiences of social life to school manuals and curricula, placing an emphasis on learning about the concrete realities of the African people, the historical processes that they were challenging at the time – that is, colonialism – and the violent and structural relations that emerged from its practices. (27)

Colonialism and the legacies of exploitation and uneven development it produced can be considered a disaster (Bonilla, 2020). The legacies of colonialism also affect who and what are vulnerable to climate events such as hurricanes, droughts, floods, etc (Moulton & Machado, 2019; Taiwo, 2022). Furthermore, the uneven development and structural racism still in place heavily determine decisions on what is prioritised in recovery efforts following a hurricane for example (Overton, 2020). For example, since the tourism industry drives much of the economy in the Caribbean, the U.S. Virgin Islands prioritized rebuilding cruise ship terminals and hotels over low-income housing and schools to help fund the recovery process. Furthermore, people residing in informal settlements did not qualify for FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) and HUD (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development) funding because they did not have official documentation (ibid). Therefore, disaster-based education must be explicitly anti-colonial at its fundamental level. Using the strategies of the PAIGC such as discussions using direct language about the concrete realities of the people led by ‘militant’ disaster teachers from their own communities could help dismantle still present colonial structures, produce new knowledge on disasters, as well as provide a space to mobilize around disasters to create a better alternative to aid based or disaster capitalist forms of recovery that we often see today.

Space (land) and the role of the state matter when discussing education as a core part of liberation struggles. The militant schools in Guinea-Bissau had to be mobile, dynamic, and easily transportable to move with and hide from the ongoing war. How do we translate this into more contemporary decolonial struggles where the fight is against the State rather than a foreign occupying power? In the next section, I focus on a current decolonial struggle: Cooperation Jackson’s struggle for economic and black liberation in Jackson, Mississippi. Buying land is instrumental for Cooperation Jackson to exorcise themselves from systemic injustices. Moreover, the institutional foundations of Cooperation Jackson provide an example of producing an alternative way of life while simultaneously resisting oppressive structures that produce vulnerabilities, the second part of the framework.

Cooperation Jackson and a ‘Just Transition’

“National liberation, the struggle against colonialism, working for peace and progress – independence – all these are empty words without meaning for the people unless they are translated into a real improvement in standards of living. It is useless to liberate an area if the people of that area are left without the basic necessities of life”.²

Jackson, Mississippi has become increasingly vulnerable to climate related disasters over the past decades (Akuno, 2017; Neuman, 2022). Cooperation Jackson describes, in their Just Transition primer, how the shift to industrial capitalist production required the complete reorganisation of society, initially in Europe, and subsequently wherever capitalism spread (Akuno et al., 2022). Therefore, as many argue, to address the negative effects of industrialization and the mass increase of carbon emissions into our atmosphere requires more than simply switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources. There needs to be an explicit focus on equity and justice throughout all phases of the transition (Climate Justice Alliance, 2017). Cooperation Jackson contend that a Just Transition is a systemic turn, through genuinely democratic means, away from exploitation, extraction, and alienation, and towards systems of production and reproduction that are focused on human well-being and the regeneration of ecosystems. In their goals that follow, Cooperation Jackson provide a present decolonial example of producing an alternative way of life while simultaneously working to dismantle oppressive structures without the use of overt violence.

Cooperation Jackson is the sum of four interconnected and interdependent institutions: a federation of local cooperatives and mutual aid networks; a cooperative incubator for start-up training and development education; an “Economic Democracy School” to broader social consciousness; and a cooperative credit union and bank to control democratic financial investment in the people. These institutions are seen in the 5 “cities” the cooperative aims to develop. There is the Solidarity City through the development of the green worker, self-managed cooperatives and an extensive mutual aid and social solidarity programs, orgs, and institutions. The Sustainable City by developing an eco-village, community energy production, and sustainable methodologies and technologies of production and ecologically regenerative processes and institutions. They hope to stay on the cutting edge of innovation through the Fab City and developing 3D print factories that anchor community production cooperatives in forward looking institution. Their Workers City develops an all-embracing, class-oriented Union-Cooperative to build genuine worker power from the ground up in Jackson. Finally, the Human Rights City will develop a human rights institute to craft a human rights charter and commission for Jackson (Akuno, 2017).

In addition to institutions and types of city that are at the core of Cooperation Jackson’s mission, the “planks” of a Just Transition include principles such as, Decolonisation and the restoration of Indigenous and “traditional” peoples’ sovereignty; Reparations and Restitution, Ancestral and Science based solutions; Agroecology, food sovereignty, and agrarian reform; Recognition of lands rights; a just distribution of reproductive labour; and have a development vision that moves beyond endless economic growth. The aim is to shift the political and economic power and move towards a regenerative economy from an extractive one. For this transition to be just and equitable it must redress past harms and create new relationships of power through reparations (Akuno et al., 2022).

As we have seen recently in the backlash to critical race theory being discussed in US schools (Su, 2007; Mutua, 2023), it may not be possible to incorporate decolonial disaster education into the current public school system. This education may have to operate outside of the system, informally, and dynamically to move and flow with the struggle. This could be in the form of occupying land by purchasing a space, as Cooperation Jackson do, or having open air forums that are easily transportable, as Cabral and the PAIGC used.

Regardless, space matters when it comes to educating the populace on deep-rooted unjust structures that contribute to their vulnerable conditions. Applying these lessons to DRR allows us to think about the spaces in which we, as scholars and activists, operate and what structures we are seeking to dismantle. The spaces used to educate on hidden oppressions could help illuminate new possibilities for just futures. For example, community focus group sessions taking place next to a rebuilt luxury hotel while local housing is still in ruins would likely generate more dynamic discussion than a government conference hall. Similarly, we must be aware of who is leading these discussions, the questions asked, and what are the outcomes to not perpetuate neo-colonial forms of knowledge extraction.

In the next section I discuss how mobilizing in a disaster space must be a form of internationalism from below in order to build solidarities across space and time and mimic the movement of the hazards themselves. The movement of ideas regarding decolonial disaster mobilizations is crucial for a just and equitable transition. Similarly, as the PAIGC and Cooperation Jackson emphasize, the struggle is against the structures rather than a specific people, race, and or class. It is important for DRR practitioners to think about critiquing structures in place rather than people in power, as often these people in power are victims of long-standing processes like colonialism and capitalism.

Discussion: Disasters Mobilization as a form of Internationalism from Below?

The third and final aspect of mobilizing people in places affected by natural hazards and disasters is having a balance between the local and global. A tropical cyclone does not adhere to international or interstate borders, but instead its movement is transboundary affecting multiple locations with differing socio-economic and political landscapes often over the span of a week or two. Therefore, mobilizing around disasters must be similarly transboundary and build solidarities across space and time. Here, this potential movement can learn from other transnational movements such as food sovereignty, indigenous struggles over recognition, and other climate justice or environmental justice movements that join the need for sustainability and social justice. Specifically, how these bottom-up movements utilize formal and informal international struggles to spread their message, build transnational solidarities, and gain international recognition from institutions like the UN (Bjork-James et al., 2022).

Two key actors of the global climate justice movement: the transnational agrarian movement La Via Campesina (LVC), which is a network of peasants and small farmers’ organisations, and the International Indigenous Peoples’ Forum on Climate Change (IIPFCC), which speaks for indigenous peoples (IP) at UNFCCC meetings present examples for how to use informal and formal spaces to advance alternative development paradigms. Both are recognised as speaking on behalf of those who will be (and already are) most affected by climate change (Gonzalez, 2012; Havemann, 2013). Both reject and reform structures built to have NGOs speak for them and instead participate in global governance debates using their own voice (McKeon, 2009). Both movements have an ability to organise transnationally and find common ground across the Global North and South. These movements have opened up new pathways for solutions at UNFCCC’s Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings by expanding the framing of human rights to include their local and global struggles (Claeys, 2015). They have used climate discussions as political but also legal opportunities to advance their rights-based climate solutions (Claeys & Delgado Pugley, 2017). This poses the question; how can global and local climate discussions be used to advance alternative solutions for disaster risk reduction as well as recovery efforts?

I view these movements as forms of internationalism from below, which describes bottom-up movements which are transnational and transboundary and actively work to shift institutions of power and injustice that produce uneven development and climate change. A transnational and transboundary movement that mobilizes people in a disaster space would further aim to address the deep-rooted structures that produce vulnerability to natural hazards and the various types of disasters that have been described in this paper from tropical cyclones to colonialism.

It is important to state that the context in which the liberation struggles mentioned in this paper deploy these techniques matters. However, advancing DRR scholarship to analyze the effect of adopting practical on the ground techniques used by movements that similarly battle against hidden unjust structures can open up new pathways for transformation post-disaster. In order to redress past harms and shift political and economic power there needs to be an understanding by scholars and practitioners of where and how these harms are experienced every day in the current system. This is where a militant education project similar to Cabral’s could become useful.

Many DRR scholars discuss economic and political vulnerability in the same vein as climate and natural hazard vulnerability because they form an interdependent relationship that perpetuates vulnerability (Pelling & Garschagen, 2018; Borges-Mendez & Caron, 2019). Disasters often result out of structural inequalities that become apparent when a natural hazard such as a hurricane, flood, drought, etc. hit an area (Birkmann et al., 2010). Disasters can be an opportunity for change because for a brief moment some of the structural inequalities producing vulnerability become visible which can lead to transformation. This has happened sporadically throughout history, for example, the Nicaragua earthquake of 1972, which killed at least 10,000 people, is considered a turning point for the country’s political pathway, as shortly after there was a regime change from US backed dictator Somoza to a more Marxist democratic path and the rise of the Sandinistas (Olson and Gawronski, 2003; Lee, 2015). However, there are more examples of post-disaster desire for changes petering out or being corrupted than ones leading to greater equity and less vulnerability. So, there needs to be more of an effort to take advantage of these “windows of opportunity” and counter forms of recovery that further entrench inequalities. Whether these changes lead to greater justice and equity to reduce vulnerability is not a given (Solecki et al., 2017). DRR practitioners could ensure these windows of opportunity post extreme event promote equitable and just recoveries by incorporating practical on the ground techniques and practices used by Cabral, Cooperation Jackson, and Transnational movements.

Conclusion

Figure 1: Framework for mobilizing in a disaster space

I argue in this paper that mobilization efforts in a disaster space must have three components. 1) The movement must have a strong foundation of decolonial education that is led by local people who have lived experience of how the colonial forms of injustice produce vulnerability to natural hazards. 2) An alternative must be presented simultaneously while dismantling unjust structures as shown by Cooperation Jackson and their core institutions. 3) the movement also be transboundary and aware of international solidarities that can be form by mobilizing around something which is itself transboundary. The specifics of how this mobilization unfolds depends on the context in which it occurs and should not be a framework that is generalized and forced on people and places. This will only reproduce colonial injustices that further entrench inequalities. Therefore, the beginning stages of this framework require conversations between groups to discuss the specifics of how each stage should happen. Finally, the framework and any movement must be adaptable and continuously learning and open to making mistakes as it adjusts to processes which will be actively working against any effort to dismantle unjust structures because powerful groups benefit from the status quo.

The argument of this paper was inspired by the important work of organizing the migrant labour force that travels around the US following a disaster and works in tough conditions to remove debris and dismantle destroyed infrastructure. The idea of how the organizing would differ if the focus was on vulnerability to a disaster as opposed to organizing an exploited labour force is the result of discussions in my climate justice class at the CUNY Graduate Center. Scholars have pointed out that disasters can provide an opportunity to alter the status quo because they expose structural inequities through destruction (Friedman et al., 2018; Birkmann et al., 2010; Pelling, 2011). However, in the DRR field there are still questions as to how best to implement this theory into practice. Taking from decolonial struggles from the past (Cabral and the PAIGC) and present (Cooperation Jackson), in addition how transnational climate justice movements (LVC and IIPFCC) use informal and formal spaces to their advantage (Bjork-James et al., 2022), I presented a framework for one possible way to take advantage of this window of opportunity. I am sure it raises more questions than it answers (it certainly did for me), but the hope is that it adds to the growing body of knowledge around this topic.

Acknowledgements

The idea for this paper came from rich discussions I had as part of two classes. First was Internationalism from Below with Ruth Wilson Gilmore and Shellyne Rodriguez, and the other was Climate and Environmental Justice with Mike Menser and Ryan Mann Hamilton. I would like to thank my professors and classmates for really pushing my ideas further than I could’ve done on my own. Also, thank you to Lucien Baskin, Mieasia Harris, and Jah Elyse Sayers for including this paper in their journal and the helpful feedback along the way.

Cabral Quote Notes

- Cabral, ‘A propósito de Educação,’ 24–25, translation by Sónia Vaz Borges.

- Cabral, Unity and Struggle, 241. (Cf. Vaz Borges, 2022)

Notes on Contributor

Charlie Overton is a Geography PhD Student in the Earth and Environmental Sciences Department at the CUNY Graduate Center. His work focuses on the social dimensions of climate change adaptation in urban areas and small island states. As part of the NOAA RISA Consortium for Climate Risk in the Urban Northeast (CCRUN) he has worked on creating a decision-making toolkit to enhance post-extreme event learning toolkit in communities recently affected by climate-based disasters, uncovering how resilience is reimagined and applied in contexts where previous interventions have exacerbated inequities that produce climate vulnerability, and analyzing effective community engagement approaches regarding cascading risks and compound extreme events. Charlie is also a fellowship coordinator at the NYC Climate Justice Hub, which is a partnership between CUNY and the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance. For his dissertation, Charlie is analyzing the relationship between international climate financing and framings of justice and vulnerability in adaptation and development projects in the Caribbean nation of Grenada. As part of this project, he is focusing on the role diasporic communities play in the movement of ideas around justice and vulnerability and the impact these communities have on development initiatives.

Bibliography

Akuno, K. (2017) ‘Build and Fight: The program and Strategy of Cooperation Jackson’, in Jackson Rising: The Struggle for Economic Democracy and Black Self-determination in Jackson, Mississippi. Daraja Press.

Akuno, K. et al. (2022) What is a Just Transition? a primer. [online]. Available from: https://www.tni.org/files/publication-downloads/jt_primer_web.pdf.

Baptiste, A. K. & Devonish, H. (2019) The Manifestation of Climate Injustices: The Post-Hurricane Irma Conflicts Surrounding Barbuda’s Communal Land Tenure. Journal of Extreme Events. [Online] 06 (01), 1940002.

Birkmann, J. et al. (2010) Extreme events and disasters: A window of opportunity for change? Analysis of organizational, institutional and political changes, formal and informal responses after mega-disasters. Natural Hazards. [Online] 55637–655.

Bjork-James, C. et al. (2022) Transnational Social Movements: Environmentalist, Indigenous, and Agrarian Visions for Planetary Futures. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. [Online] 47 (1), 583–608.

Bledsoe A (2013) “Black Geographies.” Unpublished MA thesis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Blythe, J. et al. (2018) The Dark Side of Transformation: Latent Risks in Contemporary Sustainability Discourse. Antipode. [Online] 50 (5), 1206–1223.

Bonilla, Y. (2020) The coloniality of disaster: Race, empire, and the temporal logics of emergency in Puerto Rico, USA. Political Geography. [Online] 78102181.

Borges-Méndez, R. & Caron, C. (2019) Decolonizing Resilience: The Case of Reconstructing the Coffee Region of Puerto Rico After Hurricanes Irma and Maria. Journal of Extreme Events. 06 (01)

Cabral, A. (1951) ‘A propósito da educação’. Cabo Verde: Boletim de Propaganda e Informação.

Cabral, A. (1980) Unity and struggle: speeches and writings / Amilcar Cabral; texts selected by the PAIGC; translated by Michael Wolfers. London: Heinemann.

Cadag, J. R. (2022) Decolonising disasters. Disasters. [Online] 46 (4), 1121–1126.

Claeys, P. (2015) Human Rights and the Food Sovereignty Movement: Reclaiming Control. New York: Routledge.

Claeys, P. & Delgado Pugley, D. (2017) Peasant and indigenous transnational social movements engaging with climate justice. Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue canadienne d’études du développement. [Online] 38 (3), 325–340.

Climate Justice Alliance (2017) Just Transition Framework. [online]. Available from: https://climatejusticealliance.org/just-transition/

Fraser, A. et al. (2020) Relating root causes to local risk conditions: A comparative study of the institutional pathways to small-scale disasters in three urban flood contexts. Global Environmental Change. [Online] 63102102.

Friedman, E. et al. (2019) Communicating extreme event policy windows: Discourses on Hurricane Sandy and policy change in Boston and New York City. Environmental Science & Policy. [Online] 10055–65.

Gilmore, R. W. (2018) Making Abolition Geography in California’s Central Valley [online]. Available from: https://thefunambulist.net/magazine/21-space-activism/interview-making-abolition-geography-california-central-valley-ruth-wilson-gilmore.

Gonzalez, C.G. (2011) The global food system, environmental protection, and human rights. Nat. Resources & Env’t, 26, p.7.

Harvey, D. (2017) Marx, Capital, and the Madness of Economic Reason. Oxford University Press.

Havemann, P. (2013) Indigenous Peoples Human Rights. In Human Rights: Politics and Practice, edited by Goodhart, 237–54. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change]. (2018) Summary for policymakers. In V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H. O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P. R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J. B. R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M. I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, & T. Waterfield (Eds.), Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. World Meteorological Organization.

IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change]. (2022) Summary for Policymakers [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, M. Tignor, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem (eds.)]. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 3–33, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.001.

Klein, N. (2008) The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. First Edition. Picador.

Lee, D. J. (2015) De-centring Managua: post-earthquake reconstruction and revolution in Nicaragua. Urban History. [Online] 42 (4), 663–685.

Look, C. et al. (2019) The Resilience of Land Tenure Regimes During Hurricane Irma: How Colonial Legacies Impact Disaster Response and Recovery in Antigua and Barbuda. Journal of Extreme Events. [Online] 06 (01), 1940004.

McKeon, N. (2009) The United Nations and Civil Society: Legitimating Global Governance – Whose Voice? Bloomsbury Publishing.

Meredith, S. (2023) ‘Big Oil peddled the big lie’: UN chief slams energy giants for ignoring their own climate science [online]. Available from: https://www.cnbc.com/2023/01/18/un-slams-oil-and-gas-giants-for-ignoring-their-own-climate-science.html (Accessed 6 June 2024).

Moulton, A. A. & Machado, M. R. (2019) Bouncing Forward After Irma and Maria: Acknowledging Colonialism, Problematizing Resilience and Thinking Climate Justice. Journal of Extreme Events. 06 (01)

Mutua, A. D. (2023) Reflections on Critical Race Theory in a Time of Backlash. Denver Law Review. 100 (3), 553–596.

Nightingale, A. J. et al. (2020) Beyond Technical Fixes: climate solutions and the great derangement. Climate and Development. [Online] 12 (4), 343–352.

Overton, C. (2020) Decolonizing Disaster Risk Reduction: An analysis of the recovery efforts of Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands, and the British Virgin Islands after Hurricanes Irma and Maria. King’s College London. MSc in Environment and Development Dissertation. 2019- 2020.

Pelling, M. (2011) Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation. Routledge. [online]. Available from: https://www.routledge.com/Adaptation-to-Climate-Change-From-Resilience-to-Transformation/Pelling/p/book/9780415477512

Pelling, M. & Garschagen, M. (2019) Put equity first in climate adaptation. Nature. [Online] 569 (7756), 327–329.

Reid, M. (2013) Disasters and Social Inequalities. Sociology Compass. [Online] 7 (11), 984–997.

Schipper, E. L. F. et al. (2021) Turbulent transformation: abrupt societal disruption and climate resilient development. Climate and Development. [Online] 13 (6), 467–474.

Smith, N., (2006) There’s no such thing as a natural disaster. Understanding Katrina: perspectives from the social sciences, 11. Available from: https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/files/retreat/files/smith_2006_theres_no_such_thing.pdf

Solecki, W. et al. (2017) Extreme Climate Events, Household Decision-Making and Transitions in the Immediate Aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. Miscellanea Geographica. [Online] 21 (4), 139–150.

Solecki, W. D. et al. (2016) An Urban Resilience to Extreme Weather Events Framework for Development of Post Event Learning and Transformative Adaptation in Cities. 2016. [online]. Available from: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2016AGUFMPA43B2206S

Stillman, S. (2021) The Migrant Workers Who Follow Climate Disasters. The New Yorker. 11 January. [online]. Available from: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/11/08/the-migrant-workers-who-follow-climate-disasters

Su, C. (2007) Cracking Silent Codes: Critical race theory and education organizing. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education. [Online] 28 (4), 531–548.

Táíwò, O. O. (2022) Reconsidering Reparations. Oxford University Press.

Vaz Borges, S. (2022) The PAIGC’s Political Education for Liberation in Guinea-Bissau, 1963–74. Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. [online]. Available from: https://thetricontinental.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/20220704_SNL-01_EN_Web.pdf.