by Natalie Willens

My grandmother died when I was 5 and other than jumping on her hotel bed in the World Trade Center while chewing on bubble gum, I don’t have any memories with her alive. My mother tells me stories of my grandma Jeri singing in smoky jazz clubs, painting her walls black so she could sleep through the day, smoothing her hands on her apron after baking pie. But I don’t know my grandmother through words as well as I know her through song.

“Work” (An Improvisation) by Jeri Southern

(Listen from 56:13 – 1:03:55)

REACH

I love asking my mother about my gramma Jeri, and that urge often rises into my throat after I’ve listened to one of her songs. My mother, who is a music producer, smiles with surprise when I talk to her about my love for music that was popular decades before I was born.

“When I was producing that Decca album of your grandma’s songs, you were always so touched by her music… even though she was gone, she had put something out there that reached you.” And it reached me in my body, in my spirit; deeply.

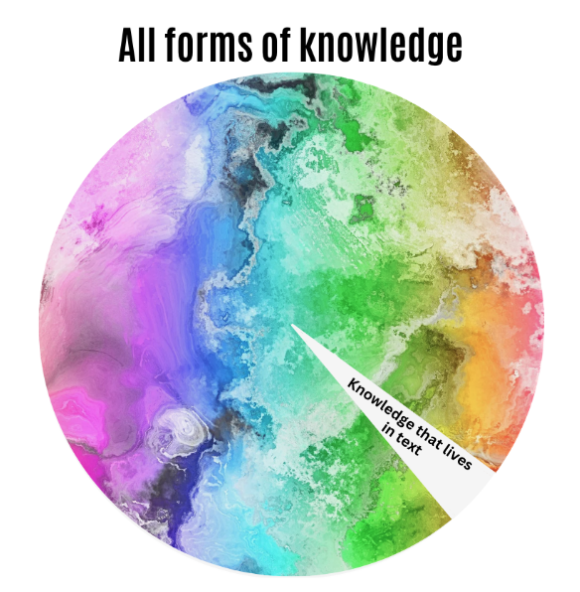

Now, as an educator, I often consider how to reach young people. And this has led me to wonder- Who does academia not reach – and who does not reach academia – when we rely on written text to tell us what we know, and how to know?

Embodied Knowledge

I am asking these questions as an attempt to queer and decolonize educational spaces and knowledge production. As a white middle class child growing up in a home filled with books, schools’ definition of “success” was in many ways designed for me. But as a young closeted Queer person, so much of my personal development happened in the non-verbal, non-textual sphere; through (secretly) watching queer coming-of-age movies I rented on DVD from the library, learning how to read gesture and facial expression in photographs and right in front

of me, listening “between the lines” to songs like “Shave ‘Em Dry Blues” by Ma Rainey, and ultimately developing an embodied intuition about when and where I could externalize my queerness. But these embodied literacies are not validated, and often actively squashed, in educational settings where exam questions require students to find their evidence solely “in the text.” Shouldn’t young people learn to develop and rely on their intuition, lived experience, and embodied knowledge – alongside written text – while analyzing the world?

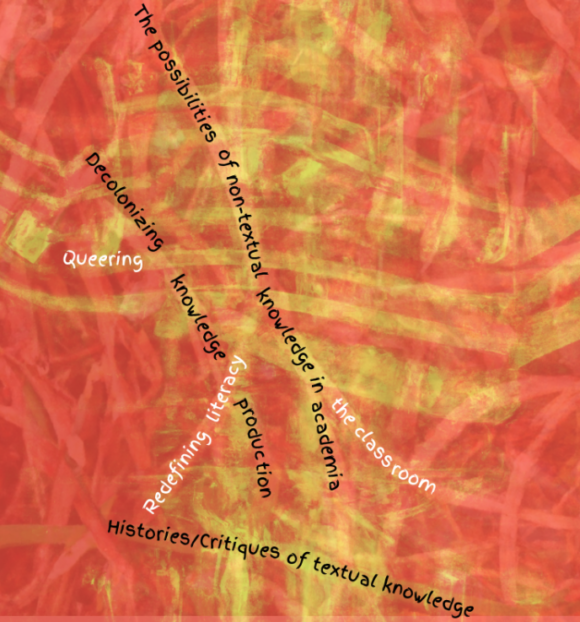

In this Ode to Non-Textual Knowledge, I hope to fundamentally expand educators’ and academics’ definitions of “literacy” and disrupt the tight binaries of valid/invalid, fact/fiction, logic/emotion, mind/body that are deeply embedded in how we teach students to read, dissect, express, and deny their understandings of the world. I am a K-College arts educator as well as a “scholar” inhabiting academia, so I am speaking both to K-College classroom practices that often consider textual academic sources as the only form of valid “evidence”, as well as academic citation practices that only consider scholarly writing as a valid source of knowledge, in order to try to both decolonize and queer the future of these spaces.

I believe that this is important from a theoretical and practical standpoint – in order to capture and cultivate a wider and richer array of knowledge in educational spaces. But just as importantly, I believe we must redefine where knowledge comes from as a project of decolonization because of the long, deliberate, and systematic denial throughout history of knowledge that has not lived in text. I feel it is critical, especially as a white “knowledge-producer,” to resist white supremacist logics that uphold the “supremacy of the word” above all other forms of knowledge expression. I have thus organized this article by weaving together text and multimedia to develop a tapestry with threads that intermingle, rather than a traditional academic paper that follows a “logical” structure.

These threads include:

Citation Practices

I have chosen to cite my references here through hyperlinks rather than through APA citations in an attempt to infuse this article with the rich sounds, images, experiences – and words – that have shaped my thinking and feeling while composing it. I avoid APA citation to convey that ideas are not generated from one single individual who succeeds in publishing a paper, but from a long entangled web of people, moments, conversations, and embodied experiences that shape how we think about the world, and which are often not credited in academic spaces. At the same time, I want to be very mindful, especially as a white scholar, not to erase the essential contributions of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) scholars. Thus I chose to cite the powerful work of many BIPOC knowledge-holders both in and outside academia, and have gratefully received permission to include some of their work here. (See the “References” section at the end of this piece for more information about the consent process I developed and followed for how and when to include other peoples’ work.) I weave quotes and images into my writing in ways that might more closely resemble poetry than academic prose in order to encourage readers to lean into the embodied experiences – the extended ringing, tensions, excitement, etc. – that arise when an idea lands, and we choose to listen to it with our body and spirit. And lastly, I chose to organize the content in this way to try to make it more accessible to readers with diverse learning styles by actively reconfiguring how knowledge looks on the page.

“Literacies”

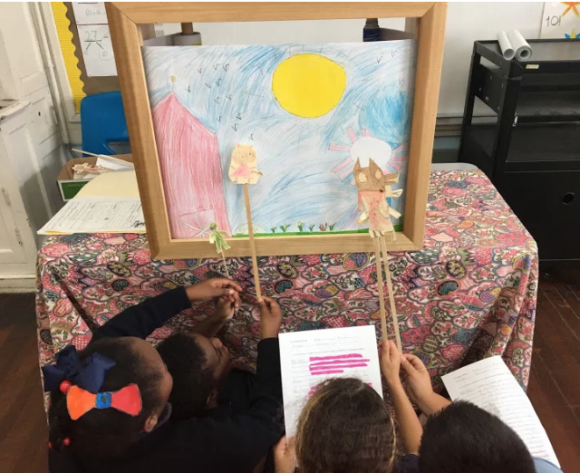

During the eight years that I taught preschool, I learned so much about my student’s knowledge – everything from how to fry arepas to how to pat a baby to sleep – through their gestures, their paintings, and their intricate oral narrations.

As I began teaching older students, I noticed that my instinct to illustrate every concept with a song, hand gesture, image – really anything non-textual – helped make content so much more accessible to all students, and particularly English Learners and students with dis/abilities. While scholars have written academic literature describing these arts-based pedagogical practices, I came to these realizations through listening/learning alongside young people and watching veteran teachers who had learned alongside young people for decades before me.

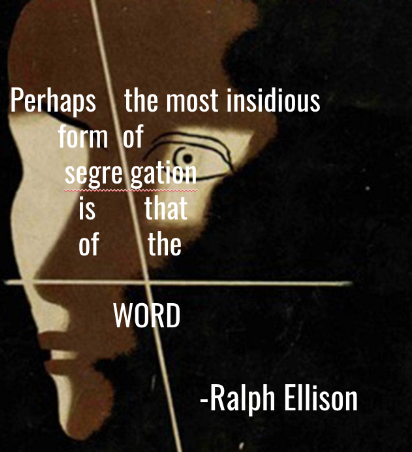

The written word is not only inaccessible to children who cannot yet read or write, but to adults who have not learned to read or write as well. According to Our World in Data, only 12% of the world population could read and write in 1820 and today 14% of the adult population around the world is still “illiterate.” The contours of these literacy statistics are deeply shaped by gendered, classed, abled, and racialized dynamics in history and education, and thus peoples’ access and ability to produce textual knowledge is inextricably linked to race, gender, class, and dis/ability. There are examples throughout history of enslavers violently withholding enslaved peoples from accessing literacy education such as through the anti-literacy laws before and during the American Civil War, which systematically prohibited both enslaved and freed Black people and people of color from learning how to read and write. Despite enslaved peoples’ coordinated resistance to acquire textual literacy skills (Williams, 2009), these forms of intellectual violence have rippled throughout history and produced inequities that persist today.

Does that mean that people who could not or cannot read or write, cannot know? Can not express their knowing in a way that academia will acknowledge or accept? Are they “illiterate” as these statistics, and many educators, would claim?

These questions are certainly about power. And while I attempt to answer the questions, I want to actively resist the need in academia to prove that I’ve “read the literature” because, as I will explore, the academic literature is incomplete. For centuries, scores of marginalized people from all over the earth have lived, breathed, spoken, danced, sweat, and died articulating ideas about power that “intellectuals” like Foucault put on paper. Many of those people were intellectuals, their intellect just didn’t live in text.

“I lack imagination you say

No, I lack language.

The language to clarify

my resistance to the literate…”

How do we write (or weave or imagine) a “literature review” of the non-textual? Of the knowledge embedded in touch and song, in dreams, in daily active resistance to oppressive systems that violently insist that all knowledge must be inscribed on the page? And how might this project help to queer and decolonize educational spaces so that they can touch and be touched by us all?

Queering the Academy

“To queer” is a verb that is grounded in the experiences of LGBTQ+ people who have had to learn to read the implicit – gesture, facial expression, silence – since to make something explicit by writing it down on paper, often places LGTBQ+ people in danger. As a queer person growing up in New York City, I never let my queerness slip from my body onto the page for fear that I would be “found out”. Instead, it was something I navigated and policed in my body from before I learned how to read or write.

And for communities whose daily existence has been a form of resistance to violent colonial systems of oppression – particularly Trans and Gender Non-Conforming BIPOC – not verbalizing or writing down knowledge could be an act of survival and self-actualization. In speaking with the Cite Black Women Collective, Dr. Dora Santana, a Brazilian “trans woman warrior, scholar, activist, artist, and story-teller,” discusses the central importance of non-textual expression as a form of self-affirmation:

“For me I’ve always been interested in painting – it’s a going back to one of the languages that for me as a child growing up was a form of expression, but also of longing, also of visualizing my girlhood…my interior world.” (23:20)

Dr. Santana is speaking to the profound importance of knowledge that lives in the body, and that often cannot be spoken with words. Painting, singing, dancing, and other non-textual forms of expression help to more fully capture the complex contours of queer identities that cannot be adequately expressed in writing. And in many cases, these non-textual articulations feel safer because of the physical and psychological violence that verbal or written articulation can elicit. This is an experience that many LGBTQ+ folx from varying cultural backgrounds have experienced throughout history in ways that have caused self-censorship.

“For years I had disowned the language that I knew best – ignored the words and the rhythms that were the closest to me. The sounds of my mother and aunts gossiping – half in English, half in Spanish – while drinking cerveza in the kitchen. And the hands – I had cut off the hands in my poems. But not in conversation; still the hands could not be kept down. Still they insisted on moving.” (Moraga, 1983, p. 32)

Why the non-textual is important

Questions about validating non-textual knowledge are deeply important for educators and scholars because they bring attention to the cognitive and emotional contradictions that we navigate on a daily basis in doing our work. For example, I have had rich conversations with both elementary school students and pre-service teachers about the urgent need to break out of the conventions of “Standard American English” (SAE) in order to validate students’ home cultures and knowledge, and then (sometimes moments later) when it comes time for my students to write a research paper, I am required – to require them – to include “scholarly” “peer-reviewed” sources.

As I read over these requirements on my assignment description out loud to my students, *hoarse, confused voices shout over me in my head*:

“What about ‘language justice’?”

Similarly, as a PhD student, I continue to have conversations in graduate courses about the “master’s tools” dilemma (Audre Lorde), where many of us argue that participating in this self-perpetuating cycle of academic citational practices invisibilizes the profoundly important contributions of knowledge holders outside academia. Yet those discussions often end with “but to change the academy, you need to get in the door, and in order to get in the door, you need to produce XYZ with X number of academic citations…”

I have woven this multimedia ode to non-textual knowledge because I believe we need to actually produce and publish work that defies these rules so that the academy changes from the inside. As benjamin lee hicks argues, we must change “what to expect” in educational spaces.

And in order to do that we must:

EXPAND our notions of what constitutes KNOWLEDGE,

and practice citing/affirming

– with CARE and CONSENT–

ancestral, artistic, spiritual, embodied

forms of knowledge that live outside text.

***

Text Erasure / Harm

While I want to resist the academic obligation to validate my understanding of these questions through “scholarly” citations, I do want to recognize and express gratitude for the long, entangled web of knowledge holders who have contributed to this work. Most people outside the academy have produced knowledge that is relevant to this piece. Particularly, people who have been unwillingly defined, denied, distorted, vilified, harmed, and erased through text, and whose knowledge and wisdom have resonated outside text.

In her talk entitled “Books Are Dangerous”, Maori writer Patricia Grace outlines four main reasons that books can be dangerous for Indigenous readers:

- They do not reinforce our [Indigenous] values, actions, customs, culture and identity

- When they tell us only about others they are saying that we do not exist

- They may be writing about us but are writing things which are untrue

- They are writing about us but saying negative and insensitive things which tell us that we are not good.

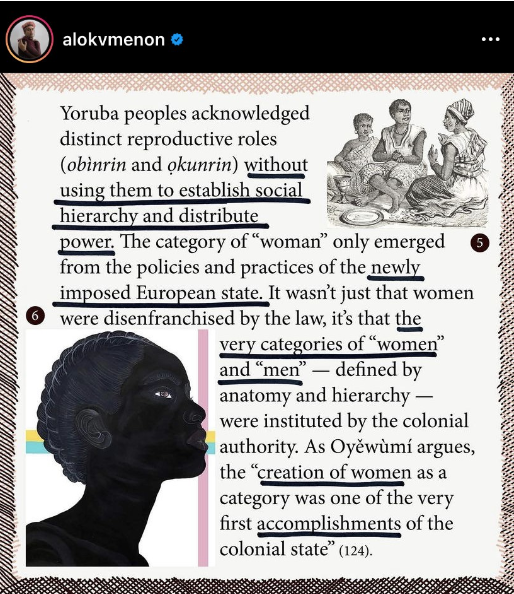

Each of these arguments about books highlights the historical imbalance in authorship of the textual knowledge produced “about” Indigenous peoples. Often, this unsympathetic representation of Indigenous and other marginalized peoples in text has stemmed from colonial historiography where the subjects of history are not the authors. I am particularly interested in the role of the written word in historiography; how our reliance on legal documents, colonial records, etc. to tell these histories erases the more complex embodied realities of people whose land has been colonized. If we depend on text to tell us what has transpired on any continent on Earth, our understandings are inherently reduced and skewed through the eyes of colonizers who saw the world through lenses of gender binaries, hetero-normativity, capitalist “progress”, and other frameworks that neither reflected nor peacefully mapped onto cultures around the globe. For example, In “The Invention of Women”, Dr. Oyèrónké Oyěwùmí describes how the categories “man” and “woman” as biological identities were imposed on Yoruba peoples through European historical writing (and colonial policies) in ways that erased the contributions of non-cis-men and set up binary categories of “men” and “women” that had been more complex and fluid before colonization.This shows how perceptions of reality – both during colonization and now as we learn about the past – have been colonized and fundamentally distorted by the written word.

Generally, colonial states and knowledge producers have systematically denied embodied knowledge – knowledge gained through experience and felt/remembered in the body. Dr. Dora Santana speaks to this from the perspective of Trans peoples’ experiences in Brazil:

“When we say that we experience violence and that is a knowledge that is embodied…for many years we were not in spaces in which that knowledge was translated into acknowledgeable data for the state or for academia.”

Instead, colonial knowledge producers (historians, scientists, philosophers, politicians, etc.) burned their own perceptions of colonized peoples onto paper. From the Latin (instead of Indigenous) taxonomy of plant species, to colonial street and building names, power drips from words. Thus, academia’s insistence on textual references actively erases knowledge and perspectives that have been wiped out with words.

The danger of images

While I hope to expand academic notions of what constitutes knowledge and where it comes from, it is also important to consider the powerful potential for non-textual artifacts to shape dangerous and harmful perceptions about reality. In “Listening to Images” Tina Campt asks:

“How do we contend with images intended not to figure black subjects, but to delineate instead differential or degraded forms of personhood or subjections – images produced with the purpose of tracking, cataloging, and constraining the movement of blacks in and out of diaspora?” (pg. 3)

In many cases, the people writing down colonial accounts of the world were cut from the same cloth as the people holding cameras, paintbrushes, etc. The power of an image to “say a thousand words” with just one glance has led to the danger of images to instantly reinforce stereotypes, perpetuate harmful narratives, and construct singular perspectives that erase those outside of the frame. Since we are consistently confronted with images in our personal and political landscapes, exploring and co-creating critical visual literacies in the classroom provides youth with more tools to evaluate and produce images that exist in, and talk back to, the world.

One related example of this is through the work of benjamin lee hicks, who considers how educators can use drawing and imagery to create more nuanced representations of identities that are regularly targeted and under/mis-represented in educational spaces. Through queer visual narratives, hicks hopes to complicate assumptions about “what a queer person “looks” like and… what someone opposed to supporting queer/trans inclusion in schools “looks” like…to prompt and support the conversations that all teachers need to start having about racism, xenophobia, and the intersecting realities of gender-based violence in our schools.” (p. 189)

Although artistic forms have often been co-opted to dehumanize, images, oral histories, music, dance, and other art forms have the power to add important nuance to flattened stereotyped perceptions about marginalized and underrepresented identities in ways that text cannot.

More examples from the classroom

As a teacher, text’s inaccessibility plays a constant role in my work. For those of us teaching in early childhood, we are pushed to find ways to make ideas come alive through song and dance because our students are still learning to read. But now even as I teach pre-service educators, I regularly confront the inadequacy and harm that academic prose can cause.

For example, when I assigned Tara Yosso’s powerful piece on Community Cultural Wealth to my pre-service teacher students, I was trying to spark a conversation about all the different kinds of knowledge our students hold, all the ways their linguistic, cultural, and social “capital” are dismissed in many K-12 educational spaces. When we arrived in class to discuss, students articulated that the 25 page reading was “challenging” and “difficult to get through.” One of my students prefaced her analysis of the text with: “I’m not sure if I know exactly what it was saying, but…”

The self-doubt that Yosso’s text induced in my students ironically highlights how their cultural capital was not being drawn upon to engage with the ideas explored in the text. Although Yosso profoundly contributed to asset-based approaches within the academy, and might not have been writing for pre-service teachers, the prose she used to communicate her ideas made them inaccessible to students who would greatly benefit from these ideas.

What if we normalize integrating *non-academic* media into academic texts in order to make theory come alive for all readers?

This Instagram post from teacher Sammy Rigaud shows first grade students freestyling in his classroom on Fridays. By offering this weekly opportunity for students to improvise and perform in front of classmates, Rigaud celebrates and leverages students’ cultural, linguistic, and resistant capital through hip hop pedagogy in his classroom. But an instagram post is not considered a “valid” source in academic publications, and often not in education courses where students are learning about pedagogy. Yet providing opportunities for pre-service teachers to both absorb and contribute “non-academic” material that concretely demonstrates theoretical concepts like Community Cultural Wealth helps them absorb and apply these ideas in authentic ways in their own classrooms and lives.

When students express their difficulties around engaging with academic texts like Yosso’s article, I often think in the back of my mind – “well, I need to prepare them for writing research papers, for comprehending academic texts.” But instead of worrying about preparing them to succeed in the academic world, why don’t I put my energy towards preparing academia for them?

PREPARING ACADEMIA

This project is not just an argument for using primary sources in history papers. It is a call to recognize non-textual knowledge as imbued with wisdom, and not needing theory or text to analyze that knowledge in order for it to become valid or worth citing/teaching in any academic field.

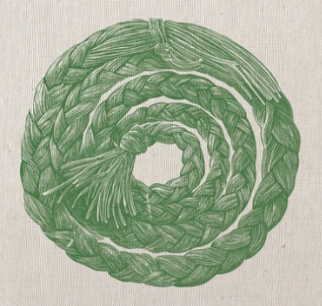

At the same time, we do not need to cast off all knowledge that lives in written text. Rather, we can recognize textual knowledge as one small sliver of all the genres of knowledge that can be woven together to deepen our understanding of the world. In the preface to her book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer brings together “scientific” ways of knowing with Indigenous ways of knowing and describes the book as an offering, a “braid of stories meant to heal our relationship with the world”:

“This braid is woven from three strands: indigenous ways of knowing, scientific knowledge, and the story of an Anishinabekwe scientist trying to bring them together in service to what matters most. It is an intertwining of science, spirit, and story – old stories and new ones that can be medicine for our broken relationship with the earth, a pharmacopoeia of healing stories that allow us to imagine a different relationship, in which people and land are good medicine for each other.”

So how does weaving different strands of knowing look, feel, play out in education? Luckily there are many people who straddle diverse academic, spiritual, scientific, ancestral, and artistic worlds, and who have similar commitments to transform and decolonize the epistemological landscape of academia. Drs. Alaí Reyes-Santos and Ana-Maurine Laura have created The Healers Project, which seeks to celebrate and record the multi-layered knowledge of women healers from the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and their diasporas.

The site, which showcases this work, provides audio clips, photographs, videos, maps, and information in indigenous languages to communicate the tacit knowledge that these healers hold and generously share. This resource provides an entry point for various ages to explore the healers’ knowledge in ways that are more accessible and informative than an academic paper would be. Knowledge about plants and healing requires overlapping visual, tactile, sensory, and spiritual experiences that are often downplayed or erased in text-only resources. It also requires tapping into frequencies that cannot be described or captured with words.

These validations of tacit knowledge provide important models for educational spaces. In our age of test-obsessed schooling, educators are pressured to drill students with “evidenced-based” ways of demonstrating their knowledge that rely predominantly on text. This over-emphasis on text denies students’ rich ancestral legacies of knowing, and erodes our millennia-old instincts to understand and shape the world through all of our senses. When we rely on text to tell us what we know, it makes us question our own knowing, our own experience of the world.

I had my own taste of this last week when the weather app on my phone said it was raining in my location but then I looked out the window and it was sunny. Rather than doubt the app I started to ask myself – is the app registering my correct location? Am I looking at the wrong hour? Is that really the sun outside? I was trusting the words and numbers on my screen more than my eyes and ears. I believe we need to teach our students – and ourselves – to begin trusting our bodies and our ancestors’ embodied knowledge again.

TRUSTING EMBODIED KNOWLEDGE

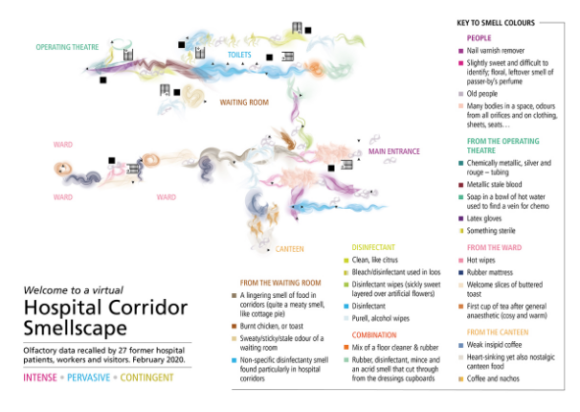

(Re)igniting this embodied trust can take many forms. Kate McClean makes sensory maps that help visualize the olfactory experiences we have in various landscapes.

Asking students to describe the world like this through more than text increases their attention to detail and nuance, provokes new questions, and makes their knowledge more accessible to the public.

Multimedia tools like Are.na allow users to collect and display various non-textual sources including websites, sound bites, and images in order to construct a multi-faceted representation of an idea or response to a question. This type of interface validates experiences and knowledge that cannot be captured in text, and profoundly expands the ways students can answer a question.

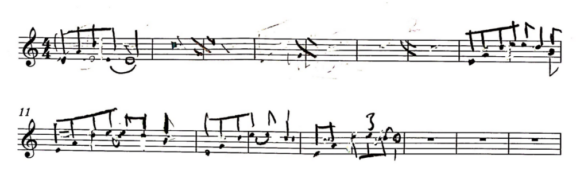

These kinds of tools also diversify the variety of literacies that students can develop and use to record and speak to the world. For example, young people can learn ways to read and write sound. When I was younger I would play on my family’s piano and when I composed songs my father would write them down through musical notation on a staff. My mother recently told me that when she was in kindergarten, she attempted to “write” a piece of music like her mother by placing and shading in random notes on a sheet with musical staves that was lying near their piano. My grandmother picked up my mother’s musical sheet and played it for my mother, so she could hear what my mother had “written.” I never learned how to read or write music because these forms of musical literacy are rarely taught in “core subjects” in school, but they provide powerful ways for young people and adults to record their experiences, ideas, and visions through sound.

Similarly, in order to truly validate non-textual knowledge in educational spaces, we need to fundamentally transform how we assess student learning. Although educators continue to develop creative, anti-racist assessment models, and education stakeholders have developed momentum in resisting narrow evaluations of student achievement, we cannot re-imagine how students demonstrate knowledge until we re-define what knowledge actually looks like.

Does academia deserve this knowledge?

Despite these expansive possibilities, I wonder and worry about how all this magic will alchemize in the ivory tower. Although I yearn to hear my grandmother’s voice as she sat at the piano and taught her students to sing in falsetto, I feel protective of her wisdom; I am not sure I want to subject all her teachings to the academic gaze.

What does the academy want with this knowledge? How will it use it, and to what end?

Ultimately, the question is not whether non-textual knowledge is worthy of inclusion in the academy, but whether the academy is worthy of holding it. Would my gramma have been okay with me including stories of hers, vulnerable moments of her at the piano in the safe solitude of her home…? As we begin to normalize the collection of oral and multimodal histories in classrooms and academic citations, we will need to develop care-full methods for determining whether the knowledge we are capturing can live safely in the hands of academia; With greater power to reach and be reached by non-textual knowledge, comes greater responsibility. Will capturing this through video put our undocumented classmates in danger? By placing these ancestral teachings in an academic article, do I put them at risk of being appropriated and/or commodified? Would my grandmother want to be included here? Asking these kinds of questions and co-developing frameworks with young people around consent and online safety are integral to doing this work in care-full, consensual ways that honor the values of knowledge that lives outside text.

And one of the most important ways for determining whether we are worthy of a recipe or song or salve stems from our personal relationships with the producers of these non-textual knowledge forms. Since my grandma Jeri is no longer living, I called my mom while biking home one afternoon just as the March frost was thawing, and asked her if she thought her mother would be okay with me uploading her unpolished composition into an essay that eventually might be public to the whole world. We exchanged ideas about vulnerability, consent, my grandmother’s perfectionism, and how deeply that 6 minute recording moved me in my body. “She was putting something out there that reached you…”

As I pedaled past green buds popping their heads out of the soil, tears streamed down my face as I relived the memory of that recording and felt in my body how hard my grandmother and mother worked to get me here, writing these words on the page. I realized that my oral research about my grandmother was bringing me closer to my mother, unearthing new stories she had forgotten, and deepening our intimacy as we navigated together this question about whether my grandmother would want her work included in this way. Ultimately, we agreed that she would have loved to support the artistic exploration of her grandchild, and would feel touched that her own art continues to inspire my own.

Textual research can be such a lonely and distancing endeavor – if I could only learn about my grandmother through newspaper articles, I would only know her through the words and perspectives of her critics. Ultimately, this is my way of keeping her alive, in ways that would not be possible if I could only show you with writing.

*A Note on References:

In preparing to publish this piece, I began reaching out to the artists, activists, and scholars that I reference, in order to confirm that they would agree to have their work, and/or their photographs included in the article. Generally, I reached out to anyone who is currently living and whose work I reference visually in order to ensure that they felt comfortable and approved of the image or combination of images and text that I chose to “represent” them. I gratefully received consent – sometimes enthusiastically – from all of the people who responded to my email communications. In some cases, I never heard back from someone, despite multiple attempts I made to reach out. In those situations I decided to delete any content that is not already made public by them. For example, I deleted an illustration that one scholar created that was only available through a pay wall, and omitted a quote I had included from an online talk I attended, since I was not sure if the speaker would consent to me writing down her words during the talk. I also kept an image that I got from a public instagram account, but cropped the image in order to protect the identity of the child whose image is included. I have not arrived at an exact “science” for navigating care-full consent, but it has been generative to engage in conversations with the people whose work deeply inspires and shapes me. I welcome any feedback so that I can continue to develop care-full citation practices!