by Kaleb Germinaro, Ph.D., University of Illinois – Chicago

Abstract

This paper applies a Black geographies lens to sociocultural learning and reshapes how we understand learning as consequential to the sociospatial production of physical space and infrastructure. Through a design-build program run by Sawhorse Revolution, youth learn to design and build physical spaces in the wake of the rapid displacement and gentrification due to systemic racism in the Central District and South End of Seattle, Washington. I argue that a learning lens on the design and build process unveils what gets hidden through the painful processes of gentrification, rendering folks’ process, and displacement/dispossession. This paper uses Black geographies framing to understand learning and spatial production from a Black perspective that centers on Black stories and experiences to understand the role of learning as a tool for resistance. What is revealed through the spatial reorientation to Blackness as we understand learning is the convergence of two ways youth employ learning as a spatial resistance and justice tool as they design and build spaces. I show how youth learning can be a mechanism for city-making, belonging and spatial justice. Further, the intentional design of the learning environment shifts the spatial production process, setting a standard for youth involvement in city-making allowing them to be seen as urban alchemists as they employ design and its connection to aesthetics. The paper thus theorizes that our spatial orientations through a Black perspective allow us to understand learning as a tool for resistance and organizing through collective action. As youth learn to design, they engage in an urban alchemical process that disrupts geographic harm and reshapes our cities.

Introduction

In 1968, the Black Panther Party made its first chapter outside of California, located in Seattle, WA. That chapter was located in Seattle’s Central District and a historically Black community experiencing rapid displacement and gentrification over the last 30 years. This process of rendering Black folks placeless through dominant power disrupts the Black sense of place, often virtually impossible under white supremacist notions of control and domination (McKittrick, 2011). Further, Black sites of resistance call attention to spatial techniques replicated from plantation slavery, yet a Black sense of place revitalizes tools to resist white supremacy. The Central District has emerged as a site of resistance and Black geographies which are “subaltern or alternative geographic patterns that work alongside and beyond traditional geographies and a site of terrain of struggle” (McKittrick, 2006, p. 7). The Central District itself has experienced rapid gentrification and displacement and the community has reposed in a way to both reconstruct and build what McKittrick refers to as a Black sense of place. A Black sense of place draws attention to geographic processes that emerged from plantation slavery and its attendant racial violence’s yet cannot be contained by the logics of white supremacy… it is a location of difficult encounter and relationality… is not individualized knowledge—it is collaborative praxis. It assumes that our collective assertions of life are always in tandem with other ways of being (including those ways of being we cannot bear” (McKittrick, 2021, p.105). However, the Central District is an ongoing Black geographical reclamation of space through emerging and returning businesses, cultural spaces, community organizing and large-scale efforts to disrupt the ongoing agenda of quelling the Black sense of place.¹

Although Black homeownership and population have declined dramatically in the last 30 years.² The Black geography of the Central District persists in many ways through cultural space reclamation, public space activation, community land trusts and the sharing and holding of stories to counteract the gentrification of the Central District. The neighborhood itself went through many spatial injustices to various groups of people, including the original people of these Coast Salish lands, the Duwamish and Lushootseed speaking peoples. Also, notably the displacement and internment of Japanese Americans during WWII and the racially restrictive covenants that led to the Central District being considered a Black neighborhood with a population peaking at 80% in the 1970s and lower than 18%.³ Over the next decades, urban decay and divestment of resources to the neighborhood led to urban renewal. Simultaneously, the technology boom in Seattle led to the astronomical gauging of the wealth of particular types of people through the 1990s and ’00s. Particularly, large local and foreign real estate firms have bought up multiple plots of land in the Central District and manage a lot of the area at the moment. Reclamation and spatial resistance have been ongoing in the Central District since the William Grose family purchased 12 acres in the area in the late 1880s and sold the land to Black families (Taylor, 2022). Throughout this history, Black families and people within the Central District have resisted dissents of white domination and displacement through today. Quintard Taylor (2022), a historian, described the experience and trajectory of Black people in Seattle from the days of William Grose to the Civil rights movement:

As a self-proclaimed politically progressive city, Seattle celebrated its image as a multicultural, multiracial democracy where opportunity was open to all. The reality for the entire century between 1870 and 1970 was vastly different for most of Black Seattle. . . the forces arrayed against Black aspirations were sometimes supported consciously, and often unwittingly, by the vast majority of Seattleites who chose to ignore the plight of the impoverished, the uneducated, the economically disadvantaged—particularly if they were of a different color. (p. 239)

Seattle’s progressiveness is at the expense of Black, Brown and Indigenous communities (see Shange, 2019 for further analysis of this in San Francisco). For example, the Central District is now dubbed an Art and Culture hub, which is regularly a trend in large cities as rebranding of Black neighborhoods through arts and culture means the displacement of those who built that space (see Denver’s Five Points, Philadelphia’s South Street, & Phoenix’s Roosevelt Row etc.). This line of description and thinking holds as it affects the schools and educational experiences of learners in Seattle that are Black, Brown and Indigenous. With skyrocketing property values, massive displacement and divestment from schools, the continued geographic harm and spatial violence persists well into the twenty-first century through busing, the gutting of communities of color and rapid divestment of community resources for the attraction of white, affluent and bustling tech scene. In alignment with this assertion, Pearman (2020) calls attention to the correlation between the white population increase in urban schools and gentrification in those areas, leading to a decline in Black and Brown populations. A decline in enrollment signals gentrification and displacement through rising property taxes, housing prices and cost of living, and school closures, especially when intermixed with a limited affordable housing supply.⁴ As such, many cities are experiencing these effects of white affluent and progressive patrons moving back to the city as cities follow up on the Urban Renewal Act⁵ that destroyed large swatches of urban communities between the 1940s and 1970s (Davis & Oakley, 2013). This is occurring again with various factors contributing to the displacement of Black people (Pearman, 2020).

As a disruption of Black space, Black learning is further challenged through various mechanisms related to stress, wellbeing and connections to place (Germinaro, 2022). Although long and challenging, this process demands a collaborative praxis based on relationality across racial and cultural bounds (hooks, 2009). In doing so, one of the main mechanisms to reframe is to inquire about “where we know from,” is to understand the purpose of learning in the larger urban ecology while honoring and restorying space through Black methodologies (McKittrick, 2021, p. 131). There aren’t ample opportunities for youth to design and advocate for their built environment/infrastructure to combat intersectional spatial injustice. School environments often pose as sites of suffering, one that disrupts the spirit of youth learning (Dumas, 2018). This positions and highlights space as a key component in learning (Tate et al., 2012). Therefore, we must also pay attention to the reverse, learning as a key component of space and its physical and social production.⁶ Physical refers to learning environments that guide the infrastructure of the built environment, and social refers to belonging within and to a learning community/environment.

A roadmap note to the reader(s):

Below I will highlight the physical and social learning determinants of spatial production. First, I will leverage Black Geographies as a framework to showcase the ways the physical product of a learning environment leads to spatial justice in high displacement areas, rendering the learners and houseless community as having a place, enacting spatial justice. “Spatial (in)justice refers to an intentional and focused emphasis on the spatial or geographical aspects of justice and injustice. As a starting point, this involves the fair and equitable distribution in space of socially valued resources and the opportunities to use them” (Soja, 2009, p. 2). Further, I will highlight how the learning environment enacts, supports and promotes agency. I will detail how the youth employ the learning environment as a means for reconstructing and unpuzzling the space of their community. Also, youth are rendered placeless through mechanisms of adultism, racism and sexism and other intersections (see Taylor & Hall, 2013). This is problematic in that it decenters their expertise in advocating for and creating space for themselves and others within the context of the city through spatial and locative literacies (Taylor, 2017). When discussing who is generally deemed able to create/have the ability to make and construct physical representations of place, we must consider how youth can offer keen insight into the future of spatial justice and the design of our spaces.

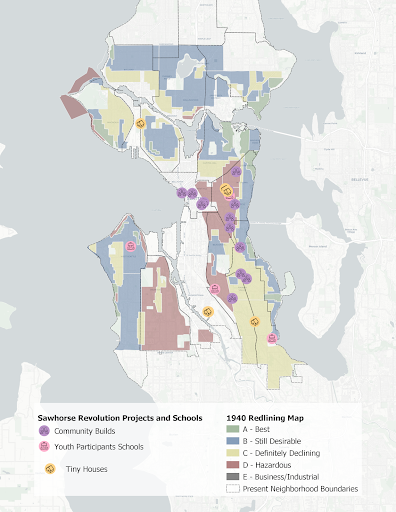

Secondly, in highlighting learning as a resistance tool for spatial justice, I want to detail the urban ecology Sawhorse Revolution operates in. Therefore, I conducted a critical race spatial analysis to deepen my analyses of the significance of these projects (Solórzano & Veléz, 2015). This map (Figure 1.1) showcases the design-build Sawhorse Revolution has produced over the last nine years. The entirety of these projects is youth-directed, built and placed. In looking at this map, we can identify the locations of these buildings, predominantly being placed in previously red or yellow-lined areas⁷ of the city. This further builds on Black geographies and studies of learning by displaying how youth engage in sociospatial historical issues across shifting geographies and the ever-changing timespace to build a just future (Gilmore, 2022; Gutiérrez et al., 2019).⁸

Figure 1.1. Sites of Resistance produced by Sawhorse Revolution youth to date in Seattle, making and maintaining sites of resistance and/or homeplaces within formally redlined and systemically marginalized areas experiencing rapid gentrification and displacement.

More specifically, since youth decide what projects they are signing up for and the intention for Sawhorse Revolution to ensure their buildings are addressing displacement of bodies, ideas, knowledge and culture, this showcases the implications learning has on social and spatial justice. The work of small out of school organizations showcases the power of education to produce infrastructure as anti displacement strategies that centers and enacts justice through spatial means (Veléz & Solórzano, 2017). Redlining in Seattle has contributed to the astronomical divestment in low-income and communities of color until the emergence of tech companies and pressure for urban renewal. Coupled with this unfortunate reality, stark single-family house zoning laws causing a housing shortage, and unchecked gentrification, people and families have been displaced. Therefore, youth can have agency in their decision-making to counteract the geographic harm through their engagement (Germinaro, 2022). In doing so, learning allows them to address and build a sense of place within their city. To address this issue, the organization started building tiny homes for the unhoused and providing beautiful, elegant and moveable dwellings to render people worthy of having a place within the city.

Thirdly, Black geographies lend themselves as a framework to understand and position the learning process (design, environment and affordances) as a geography to highlight how we envision the approach and build out of our physical and social environments (Bauer & Sandolt, 2018). Learning has a key focus within the urban ecology that guides this process differently, complicating the various layers and dimensions of learning as a spatial practice while also making a rhetorical shift in thinking through the ways youth learn to advocate and make changes to their built environment through the design process. Furthermore, positioning the power of geography and spatial learning can promote healing by combatting spatial injustices (Germinaro, 2022; Taylor, 2017). I bring these bodies of literature and ways to understand how we can view youth as urban alchemists. I introduce this idea as one that builds on Fullilove’s (2013) nine elements of urban alchemy. I particularly focus on two elements that youth engage, those being unpuzzling fractured space and making meaningful places, something they have no choice but to do with the cities we are presenting to them.

I hope to provide insight into how learning frameworks can support understanding and studying social and cultural geographies (i.e., identity resources as a way to understand tools and their uses in the learning process to make space). Building on geographies of learning and physical spatial justice production, I showcase the placements of Sawhorse Revolution’s youth design-build (i.e. tiny homes, community builds, etc) projects layered over redlined maps to showcase the ecosystem the youth are building of the spaces they engage in producing. Geographies of learning are defined as “the importance of spatiality in the production, consumption and implications of formal education systems from pre-school to tertiary education and of informal learning environments in homes, neighborhoods, community organizations and workspaces” (Holloway & Jöns, 2012, p. 482). Furthermore, this study looks at a youth design-build program and organization, precisely one program that allows youth to pick a client, design a space for them, then build the space for them in a high gentrification and displacement area. I will weave together different theories and arguments to anchor these ideas by 1) the ways learning connects to historical spatial connections, 3) spatial justice and power disruption and 4) Black Geographies and learning environments. The findings will detail how I’m viewing youth as urban alchemists and their process for engaging in that process. This program also calls attention to spatial realities and understandings from a Black perspective, instituting Black methodologies to frame and understand learning as a tool for liberation through spatial production.

The Offerings of Black Geographies to Studies of Learning

Building on Black feminist traditions of understanding space, the building of homeplaces are a form of resistance to the displacement of Black people and, more broadly, people of color in US cities. Homeplace connects to the cultivation of belonging in learning environments, a belonging that heals and builds on resistance that occurs through relationality (Meixi, 2022). Thus learning facilitates healing (Germinaro, 2022). In essence, placing ourselves in the future is a healing practice guided by belonging (Kirshner, 2015). Similarly, Black geographies highlight the connections between these acts of violence and abuses of power and how Black women have resisted and manipulated these spaces from within to socially produce space. For example, bell hooks (1990) presents the concept of the homeplace as a space constructed by Black women who have historically survived and resisted white patriarchal power and supremacy. For my project, I use the operational definition by Bettina Love, where a “. . . homeplace is a community, typically led by women, where white power and the damages done by it are healed by loving Blackness and restoring dignity and also acts as a site of resistance” (Love, 2019, p. 63). Sites of resistance do promote healing and resistance to oppression while positioning Black girls as sociopolitical and historical actors (Kelly, 2020). In doing so, sites of resistance enable the activation of tools for combating oppression through learning (Germinaro, 2022).

As a subset of Black studies, Black Geographies is a critical methodological and analytical tool to interrogate issues and questions at the intersection of space and learning. Through Black geographic concepts of spatiality, I interrogate the design of justice centered learning environments that focus on identity, belonging and building a culture of a place through physical space production. Further, design and building as a spatial and cultural practice promotes resistance to what is considered art and moves past the rigidity of arts education. For example, spatial aesthetics of gentrification and displacement are evident in and around our cities (Summers, 2022). Aesthetics and design also formulate ways and mechanisms to address spatial harm through design (Summers et al., 2022). Moreover, art forms, including design, have been a site of limitation for Black and Brown students as the field privileges well-off White male artists (Mims et al., 2022). Designing and building in the community allows Black and Brown youth to see and envision themselves as urban alchemists through art and building as they develop identities related to such practice and beyond (Nasir, 2011). Additionally, design practices in the community context allow youth to also build relationships with space through the social and physical production of space accompanied by art (Charland, 2010). As a resistance tool, designing allows for aesthetics of reclamation and resistance within a city (Summers, 2021). This in turn allows for a geo-onto-epistemological understanding of how the youth enact reclamation and maintain space within a city through their design and production process.

Additionally, scholars who study learning specifically have addressed spatial justice in various ways, such as social design experiments (Taylor and Hall, 2013), mobility justice and learning on the move (Marin et al., 2020), learning for social movements (Gutiérrez, 2020), drawing connections between self and society (Kahn, 2020) and making space for self in a science center (Barton et al., 2021). I mention these various forms of how spatial justice has been taken up (and there are many more) to highlight the variations and mosaic of how learning can disrupt power through spacemaking and place-based teaching and learning practices. Youth are disproportionately affected by spatial injustices as they rarely have decision-making power over the geopolitical dimensions to advocate for themselves, including how the spaces they engage in. Additionally, Jurow (2005) conducted a study where students participated in a symbolic architectural design project. In this study, youth took on the concerns and responsibilities of what Jurow calls the figured world and how that influenced their mathematical tasks. I am taking a similar approach for this project by engaging youth in an architectural design and building a project that takes their concerns and responsibilities reflected in their intentional design and decision-making process. My project complements and differs by focusing on the concerns and responsibilities of the youth’s literal world and their approaches to spatial justice and urban alchemy through infrastructure. Space and the spatiality of agency often falls to those who are in control of a space, rarely is that youth. As Jones et al. (2016) put it:

The extent to which young people have power over shaping their geographies and how power operates within those spatialities can have long-lasting effects on how young people perceive themselves and their places in relation to others and other places. (Jones et al., 2016, p. 1153).

Thus, there’s a need to understand, confront, and reflect on how the learning environment can produce spaces that reclaim and embed resistance in the city. As Alexandre (2018) described, “people become enrolled into communities of aspiration through the presence and absence of infrastructures and that infrastructures are therefore implicated in how the city’s progress is envisioned” (p. 67). With the aim of being in conversation with these scholars, I showcase how a Black Geographies perspective can support our understanding of learning and its ability to tie spatial matters as matters of justice for Black communities (Hawthorne, 2019). Through their urban alchemical design process, youth offer insights into ways to reclaim histories, stories and relationships in their built environment. Therefore, I ask how youth within Sawhorse Revolution engage issues of power in their city and the larger effort of contributing to and preserving a Black community through design.

Program Locations, People and Methods

Our project, program planning and duration took place from Spring 2021 until Summer 2022 at two different sites in the Pacific Northwest within the United States–one indoor learning site and one outdoor building site. The indoor site was located in the headquarters of the non-profit organization that facilitated the program, where they had a dedicated classroom and educational area, also located within the southeast region of the city where the students were generally from and experiencing a host of challenges with regards to gentrification, displacement and historical spatial harm. The organization also ran three other youth programs within this space on different days. The outdoor building site was located at a local community college carpentry school in a neighborhood familiar to the youth and about 4 miles from the nonprofit’s headquarters. This site allowed for the physical buildings to be built over three months. I participated and observed an equal amount of time at both sites. However, one activity differed, and I was positioned more as a learner in the outdoor site as my expertise is not in building or carpentry.⁹ Figure 2.2 is a project and curriculum timeline that details the program’s makeup.

Figure 1.2. Project and curriculum timeline.

Demographics

Although in vastly different settings, the two sites had many similarities in layouts. Both sites were broken up into stations that reflected mini-project teams that divided the workload and allowed youth to choose their spectrum of engagement towards what they wanted to participate in. The indoor site in the fall and winter of 2021 was an open room with four large tables with photos, projects and notes strung around the walls. Students could sit where they chose and participate in group work, usually at their tables or with partners. In comparison, the outdoor area was very open and offered more movement during the spring and summer of 2022. Locations in the outdoor site were broken up by building (buildings 1 and 2) and the activities taking place (floor building, framing, cutting, nailing, sheathing, etc.). The youth within the study were all high school age and ranged from 14 to 18 from most urban neighborhoods, although two came from the suburbs. Many students noted their distaste for the learning opportunities and courses within the school (woodshops, where the classroom ratios to learn complex power tools, made it difficult to build efficiency in using a power tool.) Thus, many students opted into joining the design and build sessions that occurred weekly on Sundays during the school year for 4-6 hours at a time. Of the students involved through the design-build portions,18/20 or 90% of the students were girls or femme-identifying people of color.¹⁰

Data collection and Analysis

Following ethnographic methods, I allowed my force and interest in space and learning to be guided by what I observed and the natural conversations in the setting (Shange, 2019). In a grounded theory approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), I noted questions, assumptions and lines of inquiry to pursue as questions around space, justice, and development began to emerge during the design sessions. Codes that led to the vignettes below were agency, skill building, spacemaking and material conditions, which led to the theme of youth making and maintaining sites of resistance as urban alchemists. The design process curriculum was built on SR’s previous curricula with support from myself and mentors who all had a hand in shaping the content. We focused on promoting socio-spatial issues from perspectives around environmental justice, redlining, disability justice and mechanisms of storying a place. Through this curriculum and the lines of inquiry that emerged, I focused on the patterns that detailed potential themes as they started to occur more frequently (Charmaz, 1983). Specifically, I looked at the activities within the curricula, the associated artifacts with said activities, the formal teaching periods led by mentors, and the tools they allowed prompted students to learn through (arts, sketching, 3D modeling, 2D modeling, etc.). My in-process data collection and analysis via field notes and natural conversations (as video recording was taking the place of the context) fluctuated from teaching to practice, teaching to practice cyclically, with breaks built in to debrief and commune over food. In particular, I looked for the learning pursuits that emerged from the activities when the youth would share their process, thinking and justification for sketching or designing a particular way, exercising agency, advocating for themselves and others, and providing sociopolitical implications to their decisions (Jurow et al., 2016). For example, the ways youth moved from their aesthetic choices to highlight the ways the components of a design can be part of the storytelling of the space.

Furthermore, these activities paralleled their natural conversational reports on why they enjoyed this learning environment, what it allowed them to do and how they experienced the learning. Recordings of natural conversations, formal interviews and field notes were transcribed and analyzed in conjunction with artifacts to provide more insight into the overall story. Since my analysis took place during the program’s entirety, I was, and still am, able to check with youth, mentors and the non-profit organization to address and ask any additional questions for clarification. Lastly, two conceptual findings were chosen for detailed, in-depth vignettes and analysis to offer a story of the themes backed by data through a vignette (Toliver, 2021). I aim at mending two bodies of literature to offer how Black Geographies can offer learning theory a pathway to attend to the body, understand spatial knowledge and center the needs and wants of individuals closest to the spaces they inhabit.

Introducing the vignettes

Firstly, the vignettes will focus on and detail how the learning process produces space and infrastructure in the built environment, deeming youth as urban alchemists as they exercise resistance. Secondly, a vignette will focus on how youth employ learning as a mechanism and process to render themselves and others worthy of having a place as they apply an intersectional lens to their design process, thus figuratively placing themselves in the city by making places for those rendered placeless. These spatial production stories will be represented through maps, quotes and artifacts from the projects to provide an accessible mechanism for readers to engage with data. This mechanism of analysis, leveraging Black geographies, is appropriate as it calls attention to the building and components of a sense of place (McKittrick, 2021). Additional artifacts and/or natural conversations were supplementary data when necessary.

In the next section, I present two examples to detail how the learning process is a mechanism for producing sites of resistance. In the vignettes, youth exercise placing the placeless, including themselves through their urban alchemical process. The examples themselves are aimed at being a small representation of how youth can and should be able to support the build-out of our cities. They are also being represented as components of a highly theoretical concept, a Black sense of place, which has traditionally not been used to support qualitative data analysis. Thus, a vignette proves most appropriate to detail the key components of a Black sense of place.

Overall, I built the vignettes as composites of information across the programs conducted by the non-profit organization, specifically focusing on instances that allowed physical spaces to be built. This aims to justify using Black geographies to understand learning as a space-making and spatial imaginary process (Hawthorne, 2019). Specifically, one that confronts enforcing intersecting oppressive powers such as racial capitalism and carceral geographies that set up spatial unevenness (Freshour & Williams, 2020; Gilmore, 2022). This calls attention to spatial knowledge construction and how learning can resist spatial harm and by adding and building on abolitionist traditions of making and maintaining homeplaces, or sites of resistance (hooks, 1990). Firstly, I provide a vignette of the decision making process youth engaged in when they chose Deaf Spotlight as the client to receive the new space they were to design to illustrate the placing of the placeless and their decision making. Then I provide a snapshot of a reflection by one of the students to highlight their commitment that moves past design and to how they conceptualize interrelations between bodies and space. The second vignette showcases how learning allows youth to render themselves and others worthy of having a place, making space for themselves through their individual and collective decision-making processes. They go through a process of building design elements, then applying those to Deaf Spotlights’ wants as they negotiate their hopes for a space as well. This example further showcases their making and maintenance of a resistance space through their design process to cultivate a sense of place.

Being and Becoming Urban Alchemists

“Adults should actually listen to the youth because we are actually the future, right? We’re the ones that’s going to be the next generation, the people that are actually going to become the builders, the lawyers, the doctors, all the jobs. So it’s better to listen to the youth. Because if you don’t, we’re really the ones that have the ideas for the future. And I think it makes us feel respected and more open to talk to people, like people older than us actually listen to us and actually make us feel included.” (Samira)

As detailed above, youth are the truth and the future. In the experience of learning with Sawhorse Revolution, youth can engage in larger decision-making processes. In doing so, they can build identities as urban alchemists as they learn (Nasir, 2002). As a particular example, youth began to build a relationship with Deaf Spotlight through their deliberation and decision-making process where they chose them as the grantee. This is the beginning of drawing connections across social inequities, space for community building and the disability community. This conversation was held on Zoom, mid-week and the students read through applications that were narrowed down to four by the mentor group earlier in the week. Through understanding and identifying the relationship between the disability community, social inequalities illuminated by covid-19, and physically having a space to build community, the youth interrogate the uncomfortable relationships between bodies (themselves, the clients and others) and lacking a sense of place. The youths’ decision-making and design process yields a resolution to the interlocking social problems that they experienced and witnessed during the pandemic.

When prompted to detail their thoughts on Deaf Spotlight and their proposal, youth involved in the study mentioned in sequence ways to engage both reasons of making meaningful places that address the unpuzzling of disconnected spaces:

But there was one that talked about that specifically for the benefit of the environment. And I thought that was a really cool idea because it can help with aesthetics too, but it also is a good cause. (Carolyn)

I thought film literature and personal storytelling was kind of their main focus. And I thought that was interesting. (Hailey)

… like deaf and blind and disabled people had especially hard time during COVID because increased physical distancing, and isolation. So this place would be a really good building for them just because it will be an art center. And I actually looked at their website, and they’ve partnered with so many people. Yeah, they don’t have a headquarters too. So I thought it would be a good idea to build them one. (Thienvan)

Here we see youth wanting to build through their decision making process. They highlight the need to address how a new space could allow them to rebuild and recover from COVID stress; they also want to learn more about the Deaf Spotlight community, incorporating and seeing youth and they value the opportunity for youth to feel safe and supported. Youth call out the connections between bodies and space, and specific access to self-determination through space (Hamraie, 2018). Further, in the students’ responses they address the production of space (Lefebvre, 1991). Their responses involve reinterpreting their cultural practices in ways that are consistent with their beliefs of folks being deserving of physical space while also affirming their identities as urban alchemists.

Students continued to unpuzzle the fractured spaces during the deliberation occurring in the program’s first quarter, students noted, “I really like the fact that like it, they represent, like a community that isn’t represented that often¹¹ . . . And it’s also like a safe space where people don’t have to go through the obstacles they would like in other public places.” Here we see the connections between space, placing others and caring for various identities through design. Youth engaged in learning (see timeline in Program Locations, People and Methods section) that positioned themselves as urban alchemists while connecting to the broader community’s purpose. Their alchemical process connects the mind, body and spatial components to the broader community and development. As youth learn, they develop and build a sense of place within the learning environment and their communities, shifting perspectives of aesthetics to promote a sense of place. Furthermore, this student also reflected on the ways their neighborhood would be difficult for folks with varying disabilities:

“I think learning more about that really made me realize that, like the neighborhood I live in, it’s really hard, it’d be really hard for them to get around.” (Thienvan)

As the youth in the design-build program for this project alluded to above, they connect themselves and others within the learning process, promoting their humanity and others. In this project, the youth picked a client who previously didn’t have a space within the city. This client also represents the Deaf community. Designing for the deaf community provided an opportunity for us to embed disability justice principles into the learning process and focus on deaf space design and disability justice concerning space. As youth engaged in this learning process, they reflected on their trajectory to shift towards seeing themselves as spatial producers. One student, in particular, noted this realization of becoming a spatial producer as she reflected on the design process and midway through the build program:

“I think in the beginning, I definitely took it from the approach of my personal interests, rather than what it does for the community. I think through Sawhorse, the design, I think the design phase, I didn’t really see much of a vision, rather. But I learned more about the community. But then, during the building program, I kind of saw, wow, this is real, like, this is going to be a space for… for people. And it just blew my mind that we could do something and it was relatively fast too. And it’s just like that, it changed everything for me. And it just excited me even more.” (Thienvan)

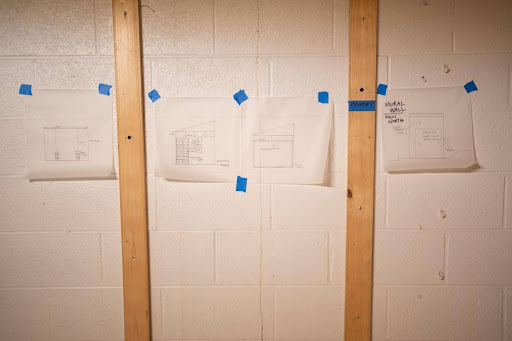

Figure 1.3. Building program photo showcasing the collective iterative group work in sequence and weaving together the applied portion of the building resistance through space, learning and seeing theirs, as well as others, futures turned into a reality.

Figure 1.4. Building program photo showcasing the collective iterative group work in sequence and weaving together the applied portion of the building resistance through space, learning and seeing theirs, as well as others, futures turned into a reality.

Figure 1.5. Building program photo showcasing the collective iterative group work in sequence and weaving together the applied portion of the building resistance through space, learning and seeing theirs, as well as others, futures turned into a reality.

Learning serves as a key organizing tool as it connects the dots through the place, land development for individuals and others within a city’s infrastructure. Moreover, the design and build learning process allows for self-determination that is socially, psychologically and culturally grounded, highlighting the necessity to understand the relationship between space critically (Davis et al., 2020). Youth inherently work at the transdisciplinary intersections that promote skill sets for urban alchemical thinking. The transdisciplinary thinking guides decision-making of the space and how designing allows for unpuzzling and puzzling intentional aesthetics for reclamation to occur, which includes their involvement in the process. Youth are also piecing together the social and cultural part of feeling in a space, which in turn represents belonging and a sense of place for themselves. A key part of their design process is ensuring the collective belonging and wellbeing of others they are in community with. They ensure meaning of a space within the communal urban ecology, particularly as they emerge into being urban alchemists. Youth promote spaces of community, education and allow their learning process to activate and determine aesthetic differences that ensure the longevity of others within a geography through designing for a sense of place.

Furthermore, Black geographies call attention to the sense of place, spatial thinking, and collective learning as a mediator for young folks to develop their agency as spatial beings who address histories of dispossession and individualism through community-based education (Baldridge et al., 2017). Youth engage in various forms of resistance, including challenging dominant narratives about who is seen as a urban alchemists, creating spaces of belonging within the city, and forging alliances with communities who share their concerns about sociospatial justice. Overall, the process of learning and design is a form of resistance that allows youth to negotiate their identities and engage in the larger urban ecology. As youth see themselves as legitimate producers of space, they build off their learning to employ that identity as a resistance strategy. Specifically they use their identities as a means of building responsibility to disrupt spatial injustice.

Process of Spacemaking, Stewardship and Learning

In running the program, Sawhorse Revolution engaged in a number of different tactics to position youth as the main decision makers within the design and build process. Through their positioning, they highlight and embody the overall process of building a collective to address various spatial issues. In their focus on the Central District and the South End, SR is deliberate in their choosing of students from the neighborhood they aim to do work in. They also embody the assertion that youth should be making key decisions in our urban landscapes. Within the SR model, we provided a wealth of pre contextual work to ground the programming that allowed us to build a spatial orientation and provide historical context to Seattle, the displacement of communities within Seattle and the ways we could support those efforts. By doing so, youth engaged in this work from the perspective of a Black sense of place being disrupted by gentrification and displacement while connecting it to the ongoing displacement of Black and Brown folks within Seattle. Further, Sam (the program manager and lead educator) set forth a goal for the learning and designs we were doing together that would disrupt this process of ongoing geographic harm, with youth leading (Nasir, 2002).

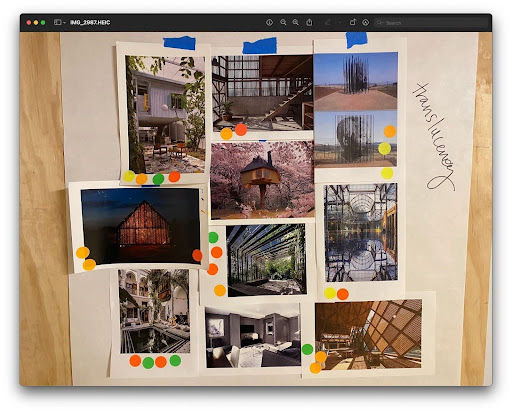

The pursuit of disrupting geographic harm through design led to increased engagement and learning more about the contexts, clients and spaces youth engaged in. For example, we engaged in a design activity called Taste that employed forms of dot voting, individual and collective decision making about aesthetic directions of the design. This exercise took place in week 2 of the 10-week design programming before the client was chosen. In this exercise, hundreds of images were laid out throughout the five tables at the indoor site. The youth and mentors were asked to pick ten images that best represented their design aesthetic, and we all had about 10 to 15 minutes. As we started, music played in the background, which was otherwise silent. As we swiftly moved around the tables searching for images, a subtle buzz of excitement emerged as images were collected and shared. As images were collected, and everyone landed on their ten representations, we posted them in a gallery walk style and went around and shared the reasons behind our choices. Some were chosen because of openness, colors, light, shade and elements of nature. Others were chosen because they were nostalgic, wanted that design feature in the future, or simply because they liked it.

After sharing individually, we were tasked with dot voting on the images across the individual aesthetic boards. Once voting commenced, we put the top 15 to 20 images on a table (see Figure 2.6). At this conjunction, Sam addressed the group and stated “. . . it doesn’t matter how many votes they have now, everything’s back on the table and everything we put onto the table is a combination of all of us and our inspirations. we’re not going to be involved. We’re gonna go over here and hang out.” At this point, the mentors/adults left, and the youth decided on ten images that would guide the final design of the space. Below we see their orientation to their choosing of the images, as they chose one by one detailed the synergies across their images such as “we think like a similar theme is like the lighting on all of them like, it feels cozy and we are creating space that connects to the environment” (see Figure 1.7).

Figure 1.6. Voting on images.

Figure 1.7. Images displayed.

The Taste exercise both allowed youth to go through the process of making their own dream space and specifically the design elements that would guide it. Youth built relationships with each other and the people they’re designing for through this collaborative process and activity. They use design as a form of humanity and humanizing (Langer-Osuna & Nasir, 2016). They center humanity on building the best space. They build the best space because they want someone to feel comfortable and that they belong in such a space. They want them to feel like they belong as a form of resistance to interlocking violence at play. They understand this as a mechanism to work through the uneasiness of social problems and make space for themselves and others. From here, they could bridge their differences and demonstrate how to move from individual wants and aesthetics to a collective aesthetic.

“. . . when we’re designing separately, or for people different than us, we have to do what’s best for them, and what benefits them.” (Samira)

“And, like, upon meeting them, I just.. No matter how it turned out, I just wanted to do the best I could for them. And because they went through so much [the pandemic] and like they’re working so hard to give their community a voice, how could you not put 100%?” (Thienvan)

Here, Samira and Thienvan detail the constant dance of building out aesthetics that reflect their ethical responsibilities of producing The act of representation serves as a key aesthetic for spacemaking, especially one that’s embedded as a process of making and maintaining a space for another group of people. The design then supported their understanding of the varying needs between self and community, while showcasing and highlighting the individual students roles in the larger urban landscape and community in which they lived. Summers et al. (2022) highlights the need to design for “the needs of those who are already here” and move away from the desires of an “ideal, future urban population” that often upholds white supremacy and neoliberal urbanism.

Building on the idea and wants of youth to be seen as urban alchemists and stewards of our spaces, one of the mentors, Sergio (who is an architect and designer of cultural spaces and grew up in Seattle), posed an interesting question in his reflections of his learnings from participating in the program.

“I learned the power of that sort of authentic curiosity that young people have and how that can be such a powerful tool in the design process as a design prompt; [design] is all experience driven or how long have you worked in the industry. But there’s something beautiful and unique about the youth perspective, and the ability to dream big. And harness that as, as an inclusive tool within design, I think is immensely powerful. What if replicate this model all over the city? We suddenly create this ecosystem of spaces in places folks really gravitate to, and really feel seen and feel heard all over the region.”

Sergio connects to the idea of design activism, a form of resistance that positions design as a tool to combat injustice, and further justifies the making and maintaining of space by youth. As they learn the practice of design they refine their urban alchemical process by maintaining the elements of resistance. As they make and maintain these spaces, they reclaim stories and aesthetics of their community. A sense of place provides an analytical approach to understanding how youth render themselves and others worthy of having a place through agential mechanisms that leverage individual and collective identities. This co-constructive process showcases how learning is a spatial practice that can address spatial and social inequities.

In reflecting on this particular activity and experience, Samira noted “in Sawhorse, we can do more; there are limits to certain ideas [in school], what you can like, [and what you] really want instead of doing what other people want you to do. You can’t do designing and stuff at school, we don’t really get to use all these tools. And really, and have a lot of like . . . a lot of time to think about what you want to do.” She notes there’s value in the process of being to think, work and design that is valuable in a learning space. The ability to take ownership and exercise what and who gets to exercise agency within learning environments. Not only do the youth feel they should belong and be valued, they understand how exclusion strips others with less power from having rights to space in a rapidly gentrifying city. In essence, youth detail what it means to have learning be a process of spatial stewardship, making and reclamation.

Implications

This project and program highlight youth as urban alchemists as they address spatial and geographical issues through learning opportunities. This project also provides insight into axiological orientations to learning as geographically constituted that complement the movement of addressing design commitments to the learning environment (Bang, 2017). Further, Black geographies offer keen insights and framings to understand space, race and learning by focusing on the body and its relation to space, the body’s relations to others, and the intersection of those relations in spatial production (Ma & Munter, 2014). For example, within urban ecologies, Summers (2019) introduces the ideas of spatial aesthetics as a tool to reclaim space. Aesthetic activism refers to the use of artistic and creative practices to engage with political and social issues (Summers, 2021). As a tool, aesthetic activism emerges as a unique response to the political and social crises of our time, including the types of spaces that are within our city, such as youth insurgent aesthetics as a way to reclaim space in the wake of gentrification and displacement.

Learning supports the cultivation of identities, specifically those that contribute to the reclamation of identities in space. Youth within Sawhorse Revolution engage in out of school learning that creates opportunities to identify as urban alchemists (Nasir, 2002). In doing so, youth disrupt various notions of who is deemed urban alchemists as they make and maintain these sites of resistance in areas that are experiencing hostile gentrification and displacement. As a community of practice (Wenger, 2011) of designers and builders, youth “learn new skills and bodies of knowledge, facilitating new ways of participating, which in turn, helps to create new identities relative to their community” (Nasir, 2002, p. 239). As a concept, Black geographies deepens the understanding of these reciprocal processes taking place in this context by added a layer of spatial literacy that connects learning and identity to the larger ecology and geography. For example, when youth are supported in seeing themselves as learners who are urban alchemists they engage learning activities with more gusto (Bang et al., 2012) and learn more. Engaging in consequential learning that not only has an actionable element but also sociopolitical implications offers more engagement. As the youth understand geopolitical issues from a historical Black perspective, they are able to reconceptualize how to address that issue and then learn more. In other words, as youth see themselves as urban alchemists, they uncover more geopolitical issues to explore ways to address.

Using design to address spatial issues builds a form of activism that is connected to, and a result of, learning and identity development (Summers et al., 2022). This process connects to the ways we can critically interrogate access to space, accessibility to stewarding space, and the ways learning allows for the cultivation of resistance spaces and the role of political work in the Learning Sciences (Booker et al., 2014). In their ability to pick and choose their builds and projects, youth exercise their decision-making skill sets to apply spatial literacies to disrupt power hegemony through space. Thus, learning and identity emerge as a key element of the social and cultural practice of spatial production as a means of resistance. Similarly, spatial analysis of learning provides insight into the complexities of urban space and the complex distribution of wealth, race, resources and opportunity when there’s an opportunity to focus on the resistance instead of ‘lack thereof’ (Tate et al., 2012). A critical aspect of this connection is the ways that identities both as a learner and urban alchemists are related to the process of becoming. Design as social justice and youth as urban alchemists contends with ways we can address power within the studies of learning from a humanities and Black studies perspective, one that is often limited and not privileged within discussions of the learning sciences (Esmonde, 2016). We must center various ways of understanding learning that reflect the settings and contexts where learning takes place, taking into account the spatial and temporal dimensions of learning in context.

Discussion

In this paper, I engage the way learning is used to make and maintain space within an urban ecology. By focusing on the Black sense of place and homeplace concept, I drew attention to learning has, and continues to be positioned as a resistance tool for spatial means (Bauer & Landolt, 2018; Leander et al., 2010). Especially one that connects products resulting from a learning environment and/or the learning process. This opens the door for designers and planners to put forth a movement beyond the adult gaze and adultism that excludes youth from their rights to the city as a way to support and engage youth in the civic process. Applying a Black geographies lens calls attention to how youth address placelessness and othering as mechanisms to address inequities through space. By attending to a sense of place for themselves and others, they disrupt the power dynamics and relations between systematically marginalized people (including themselves) and the spaces we/they inhabit. The collective we show up in the design and build process, one that supports collective action and resistance to make and maintain networks of homeplaces (Curnow & Jurow, 2021; Germinaro, 2022). Thus, a Black sense of place as a method and analytical tool for understanding a learning environment and how learning produces space lends itself to re-spatializing the built environment through social, historical and cultural relationships and representations to space. These networks extend past the individual self, yet they cherish the collective we of individual bodies and their interwoven and interdependence on one another through space and infrastructure. In doing so, youth’s maintenance and stewardship of homeplaces and sites of resistance seems to build and reflect a self-portrait of how they want their world to be, by reflecting and maintaining spaces that reflect themselves and their hopes.

When we think about learning as a spatial practice, it leads to recognizing everyday life’s lived spatial realities when we learn from specific perspectives. In this case, we feel those repercussions when a learning environment approaches spatial matters as Black matters. In other words, the best-designed learning environment leads to the best-built environment. Scholars have theorized youth as stewards of our societies, particularly as philosophers of technology (Vakil et al., 2022) and historical actors (Gutiérrez et al., 2019), and now as urban alchemists. When positioning youth in these ways, we center the design of learning environments that foreground their voice, agency and designing of worlds that make visible those rendered placeless, othered and disposable. Sawhorse Revolution’s design-build program centers those people, specifically the youth, on how they want to see their city by allowing them to build a product beyond the speculative process. The work that Sawhorse Revolution has done, along with a Black geographies framework, provides methodological insights into the ways we can understand youth and their resistance through space. They do this by providing an individual and collective self portrait of the city they want to see and be involved in that reflects their concerns and possibilities for just futures (Gutiérrez et al., 2019). They design and build spaces that reflect themselves as well as others, a mechanism that promotes the making and maintenance of homeplaces to heal from and through (Germinaro, 2022). As such, youth place themselves and others in the public consciousness unapologetically.

Lastly, theorizing youth as urban alchemists provides a lens to understand youth learning and development when they have a say in their built environment. As a school of thought, Black geographies framing renders whiteness visible and allows for learning to be positioned as a way to critique and understand how learning can challenge whiteness (Germinaro, forthcoming). Although a Black geographies are from Black perspectives, marginalized people must make whiteness visible by centering spatial knowledge of those systematically rendered placeless. Further, we must understand the role of learning in the larger ecology of a context, specifically, I am arguing for the role of learning to be better understood as an organizing tool in urban ecologies to connect across movements. Moreover, a Black geographies perspective offers methodological and analytical techniques to understanding learning as a process that facilitates the cultivation and literacy of bodies in and across space. Learning serves as a mechanism for them to have a say in the process, their learning extending past the walls of a school or program. We can build geographies that reflect the results of youth learning. Therefore I ask, what if we cherished youth’s urban alchemical process and supported their designing and building of our cities (knowing we must address their labor and provide infrastructure for their brilliance to be the main contribution while we do the backend work)?

Notes

1. Ongoing efforts and reclamation of space in the Central District.

2. Please checkout current and ongoing demographic info for the Seattle area tracking census data.

3. See more information on the historical and current project of displacement in the Central District.

4. In May 2024, we got word that Seattle Public Schools is closing 20 schools due to low enrollment and to cover the budget deficit.

5. See history of Urban Renewal here.

6. I want to shoutout Dr. kihana miraya ross’ dissertation because it’s brilliant and put me on this tip of thinking about the ways Black studies and Black space can depict/highlight learning space.

7. Redlining is a practice that refers to housing legislation that determines where mortgages, investments and money should be distributed as a means for investing in housing and property values. Colors were associated with a grading scale A-D and Green-Blue-Yellow-Red respectively. Red and Yellow areas were projected to have property values go down which were also areas where Black people were forced to live.

8. As a visual representation, we see how Black and Brown youth within SR engage themselves as urban alchemists through art and building. This is a partial description/analysis of the racialized infrastructure that young people inherited and are working within when they design and build homeplaces through SR programming; this provides context for how the organization is situated within the city context and their main focus/places of work.

9. Process of building relationships: As one of the few, if not only men/male identifying people in the space the majority of the time I leaned on Black feminist theory as I approached being in the space. I also leaned on Dr. kihana mariya ross’ (2018) work and offerings on Black girl space in education specifically to guide my approach to trust building and relationships. Similarly, as a pedagogue, culturally sustaining pedagogy really grounds my way of being within a learning space (Paris & Alim, 2017). For example, in starting with relationships and trust within this space I would approach getting to know the students by sharing my own interests and concerns with being there. For some background, I had experienced displacement growing up, often felt othered in many spaces growing up and have long been on a journey of belonging. I also noted and let them know my motivations behind supporting and being a part of this organization was mainly because I love to selfishly be involved with learning experiences I wish I had growing up. As a man in space, I had to work extra hard to earn the trust of the students, knowing that my presence has an effect on the learning ecology. I also found my strong foundational relationships with the mentors and program coordinators of Sawhorse Revolution to be a key aspect of trust building as the youth within the study were already close with them. That closeness allowed for trust to be bridged instead of built from the foundation up. Routinely I would offer up parts of my story and history as a means to learn more about the students’ experiences and this process seemed to be key to us getting to know one another. I learned there wasn’t any way for our relationships to grow without myself moving forward with care first, often asking how they were doing, probing about their families, communities and interests to prompt a dialogue to get to know one another. Over time we built trusting relationships that centered around some of our shared interests (such as dogs, design, science, art and fashion). As I’m writing this, the program coordinator texted me to participate as a chaperone in an obstacle course 5k relay with some of the students in the study. Humbled to be a part of this learning community while continuing to learn how to use my own privilege to disrupt power dynamics across the ecology. I did some do this through means outside of the strict learning environment to support the organization more broadly to support their programming through funding acquisition and pedagogy support. Some of our conversations did fluctuate on acknowledging the need for more girl and femme only spaces. As I brought these topics up in our natural conversations and later interviews, they noted the brilliance of learning from other girls of color within the space. As the only male identifying person in the space quite often, there wasn’t direct conversation around my beingness within the space, although not being an expert in the content being taught, I often opted to take the position as a liminal learner, meaning I was at any point in time a researcher, mentor, fellow learner, participant and/or errand runner. I wore many hats within the space, and personally felt this to be key in building trust as this also allowed me to physically leave the space at times allowing for there to be girl and woman only spaces as discussed by the students. I often thought consciously about the space I may be taking up, concerned about detracting from the space overall and in these positions, I would opt to pick up food or move to another area of the classroom space. I also aimed to support the cultural and ethnic identities of the students in various ways through the design of the curriculum. Whether that be our examples of designing our dream spaces or the importance of talking about the connections between our identities and spatial relationships historically, we all sat down and had more natural conversations on these topics. Specifically, one of the learners, Carolyn, and I had conversations about being Black in the Pacific Northwest, and for myself shared about being Black in Arizona. We then discussed the many benefits of being around only Black people, or different ways to seek out those spaces. This conversation traversed many natural/informal conversations over time as we discussed her wants to explore HBCUs to play sports as I had mentioned I played in college. We also talked a lot about hair, our relationships to our hair and the importance of it to us culturally. Another example of building relationships with one of the students, Thienvan, had to do with where we both lived within the city. Since we lived in the same neighborhood we often discussed the changes we would be seeing in the neighborhood, she would give me tips and the tea on the good spots to go in the neighborhood for food and I would share some of the information I offered about my favorite spots. She wanted to be an architect and we talked about the importance of her perspective as being both a designer and builder as a young woman and being Southeast Asian. Samira and Halima were cousins who spoke Oromo which is a language spoken by the Oromo people in southern Ethiopia. Early on in the study I recognized the language and asked them about it, sharing that one of my good friends at school is Oromo (s/o to you fam). They started teaching me some words and when it came to design work their designs and shadings revolved around the Oromo culture. This was our point of entry into the relationship and trust building. Also, I would often encourage their TikTok making when we would be on breaks, or sometimes during a learning session. I think this choice to allow them to enjoy their time/space allowed them to know I wasn’t planning to exercise power in that way, but rather partake in something they cared about. Later on they opted into using a GoPro to support data collection. Another student, Hailey, often shared her love for her neighborhood and community. In our conversations, we talked a lot about Filipino design, fashion and what she wanted to be after high school. She put me onto different TikTok and language trends while also being the resident videographer for a majority of the days we took field trips as she was into vlogging. I often negotiated and toed the line between professional ‘researcher’ and my own joy in building relationships based on reciprocity to reclaim community (Baldridge, 2019). My approach is not objective but rather very intentional on building connections by sharing why and how I’ve come to the work with these girls of color, my history, my life and my aims to learn with/from them in a community based educational space (Baldridge et al., 2017). I cannot and will not separate myself from the work. As the learning was in flux I aimed to also be within these liminal spaces to add value wherever I could.

10. There were also white students and one Black male student engaged during the building position of the program. Although young girls, women and femme folks, as well as Black, Brown and Indigenous folks are not well reflected in the industry demographics of architecture, carpentry and planning, they reflect the majority in Sawhorse Revolutions students. This indicates larger implications about who is deemed legitimate as a builder and spacemaker. The participants shared the need to make space for people like them in the industry and wanted to disrupt the discrepancies often reflected by the program mentors. This highlights another need for more vocational training for youth that allows them to inquire about space, thus promoting an understanding of how youth think about space (Mayega, 2018). Mentors are a vital component of the learning environment and programming taking place. Precisely for this program, we invited planners, designers and builders of color and women better to reflect the demographic of students in the program. These mentors also provided more intimate ratios for feedback, design and build sessions, insight into the industry and how whiteness infiltrates design and the built environment.

The mentors are all people of color and/or women as well. Through observations, I noted how interactions between the mentors and students centered around relationship building, humility and agency, and prompting spatial literacy. At both sites, I conducted participant observations and natural conversations about the learning environment and building days, most of which were videotaped or audio recorded. Natural conversations took place during breaks, in between activities or over lunch. With six students and the client, I conducted more in-depth recorded and filmed hour-long interviews, recordings, and audio data. Overall, I conducted over 80 hours of observations, 40 of which were recorded. Focal students were chosen based on consent to participate in the study and those who went through both the design and build portions of the programs.

11. Want to add a note that the students in the program and study did not have disabilities. They engaged and took up disability justice principles, particularly principles of collective liberation, cross movement work and recognizing wholeness. Through the lens of spatial harm across marginalized groups and communities (Black, Deaf, disabled) they drew conclusions for how space is associated with power.

Notes on Contributor

With the aim to institute theory into action, Dr. Kaleb Germinaro works in community with folks to address issues of equity, justice and space. In addition to his responsibilities as a professor at UIC, he stewards and organizes for anti-displacement work at Estelita’s Library, a small social justice library and bookstore in Seattle, WA. He keenly pays attention to and focuses on space, how his disability and Blackness are supported and/or suppressed in spaces, and how he navigates justice and liberation through his spatial orientations. Three lines of inquiry are most pertinent now:

- The role of Black and Disability theories and knowledge in how we understand the role of learning and education in climate, spatial and social justice.

- How youth engage intersections of race, the environment, and space through community design and the built environment.

- Black knowledge, methods, and stories in qualitative methods.

References

Alexandre, K. (2018). When it rains: Stormwater management, redevelopment, and chronologies of infrastructure. Geoforum, 97, 66-72.

Baldridge, B. J. (2019). Reclaiming community: Race and the uncertain future of youth work. Stanford University Press.

Bang, M. (2017). Towards an ethic of decolonial trans-ontologies in sociocultural theories of learning and development. Power and privilege in the learning sciences: Critical and sociocultural theories of learning, 115–138.

Bang, M., Curley, L., Kessel, A., Marin, A., Suzukovich III, E. S., & Strack, G. (2014). Muskrat theories, tobacco in the streets, and living Chicago as Indigenous land. Environmental Education Research, 20(1), 37-55.

Bang, M., Warren, B., Rosebery, A. S., & Medin, D. (2012). Desettling expectations in science education. Human Development, 55(5-6), 302-318.

Barton, A. C., Balzer, M., Kim, W. J., McPherson, N., Brien, S., Greenberg, D., & Archer, L. (2021). Spatial justice theory: Working toward justice: Reclaiming our science center. In Theorizing Equity in the Museum (pp. 1-18). Routledge.

Bauer, I., & Landolt, S. (2018). Introduction to the special issue “Young People and New Geographies of Learning and Education”. Geographica Helvetica, 73(1), 43-48.

Booker, A. N., Vossoughi, S., & Hooper, P. K. (2014). Tensions and possibilities for political work in the learning sciences. International Society of the Learning Sciences.

Charland, W. (2010). African American youth and the artist’s identity: Cultural models and aspirational foreclosure. Studies in Art Education, 51(2), 115-133.

Charmaz, K. (1983). Loss of self: a fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. Sociology of health & illness, 5(2), 168-195.

Curnow, J., & Jurow, A. S. (2021). Learning in and for collective action. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 30(1), 14-26.

Davis, N. R., Vossoughi, S., & Smith, J. F. (2020). Learning from below: A micro-ethnographic account of children’s self-determination as sociopolitical and intellectual action. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 24, 100373.

Davis, T., & Oakley, D. (2013). Linking charter school emergence to urban revitalization and gentrification: A socio-spatial analysis of three cities. Journal of Urban Affairs, 35(1), 81-102.

Dumas, M. J. (2018). Beginning and ending with Black suffering: A meditation on and against racial justice in education. In Toward What Justice? (pp. 29-45). Routledge.

Esmonde, I. (2016). Power and sociocultural theories of learning. In Power and privilege in the learning sciences (pp. 24-45). Routledge.

Freshour, C., & Williams, B. (2020). Abolition in the time of COVID-19. Antipode online, 9.

Germinaro, K. (2022). Healing through geography: A spatial-learning analysis and praxis. Journal of Critical Thought and Praxis, 11(3).

Gilmore, R. W. (2022). Abolition Geography: Essays Towards Liberation. Verso Books.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine.

Gutiérrez, K. D. (2020). When learning as movement meets learning on the move. Cognition and Instruction, 38(3), 427-433.

Gutiérrez, K. D., Becker, B. L., Espinoza, M. L., Cortes, K. L., Cortez, A., Lizárraga, J. R., … & Yin, P. (2019). Youth as historical actors in the production of possible futures. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 26(4), 291-308.

Hamraie, A. (2018). Mapping access: Digital humanities, disability justice, and sociospatial practice. American Quarterly, 70(3), 455-482.

Hawthorne, C. (2019). Black matters are spatial matters: Black geographies for the twenty‐first century. Geography Compass, 13(11), e12468.

Holloway, S. L. and Jöns, H.: Geographies of education and learning, Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr., 37, 482–488, 2012.

hooks, b. (1990). Homeplace (a site of resistance). In J. Ritchie & K. Ronald (Eds.), Available means: An anthology of women’s rhetoric(s) (pp. 382–390). University of Pittsburgh Press.

Jones, S., Thiel, J. J., Dávila, D., Pittard, E., Woglom, J. F., Zhou, X., … & Snow, M. (2016). Childhood geographies and spatial justice: Making sense of place and space-making as political acts in education. American Educational Research Journal, 53(4), 1126-1158.

Jurow, A. S., Teeters, L., Shea, M., & Van Steenis, E. (2016). Extending the consequentiality of “invisible work” in the food justice movement. Cognition and Instruction, 34(3), 210-221.

Jurow, A. S. (2005). Shifting engagements in figured worlds: Middle school mathematics students’ participation in an architectural design project. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 14(1), 35-67.

Kahn, J. (2020). Learning at the intersection of self and society: The family geobiography as a context for data science education. Journal of the learning sciences, 29(1), 57-80.

Kelly, L. L. (2020). “I love us for real”: Exploring homeplace as a site of healing and resistance for Black girls in schools. Equity & Excellence in Education, 53(4), 449-464.

Kirshner, B. (2015). Youth activism in an era of education inequality (Vol. 2). NYU Press.

Langer-Osuna, J. M., & Nasir, N. I. S. (2016). Rehumanizing the “Other” race, culture, and identity in education research. Review of Research in Education, 40(1), 723-743.

Leander, K. M., Phillips, N. C., & Taylor, K. H. (2010). The changing social spaces of learning: Mapping new mobilities. Review of research in education, 34(1), 329-394.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space, English translation by Nicholas-Smith, D.

Love, B. L. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

Ma, J. Y., & Munter, C. (2014). The spatial production of learning opportunities in skateboard parks. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 21(3), 238-258.

Mayega, J. L. (2018). Vocational and Technical Education for Youth Employment: What and how should it be implemented? Lessons from Selected Secondary Schools in Dodoma Municipality. Papers in Education and Development, (33-34).

McKittrick, K. (2021). Dear science and other stories. Duke University Press.

McKittrick, K. (2011). On plantations, prisons, and a Black sense of place. Social & Cultural Geography, 12(8), 947-963.

McKittrick, K. (2006). Demonic grounds: Black women and the cartographies of struggle. U of Minnesota Press.

Meixi. (2022). Towards gentle futures: co-developing axiological commitments and alliances among humans and the greater living world at school. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 29(4), 316-335.

Mims, L. C., Rubenstein, L. D., & Thomas, J. (2022). Black Brilliance and Creative Problem Solving in Fugitive Spaces: Advancing the BlackCreate Framework Through a Systematic Review. Review of Research in Education, 46(1), 134-165.

Nasir, N. I. (2011). Racialized identities: Race and achievement among African American youth. Stanford University Press.

Nasir, N. (2002). Identity, goals, and learning: Mathematics in cultural practice. In N. Nasir & P. Cobb (Eds.), Mathematical thinking and learning. Vol. 4 (pp. 213–248). New York: Teachers College Press.

Pearman, F. A. (2020). Gentrification, geography, and the declining enrollment of neighborhood schools. Urban Education, 55(2), 183-215.

Soja, E. (2009). The city and spatial justice. Justice spatiale/Spatial justice, 1(1), 1-5.

Solorzano, D. G., & Velez, V. N. (2015). Using critical race spatial analysis to examine the Du Boisian color-line along the Alameda Corridor in Southern California. Whittier L. Rev., 37, 423.

Summers, B. T., Till, J., Deamer, P., Hou, J., Barber, D. A., Nduom, D., … & Theodore, D. (2022). Field Notes on Design Activism: 2. Places Journal.

Summers, B. T. (2021). Reclaiming the chocolate city: Soundscapes of gentrification and resistance in Washington, DC. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 39(1), 30-46.

Summers, B. T. (2019). Black in place: The spatial aesthetics of race in a post-chocolate city. UNC Press Books.

Tate, W. F., Jones, B. D., Thorne-Wallington, E., & Hogrebe, M. C. (2012). Science and the city: Thinking spatially about opportunity to learn. Urban Education, 47(2), 399-433.

Taylor, Q. (2022). The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era. University of Washington Press.

Taylor, K. H. (2020). Resuscitating (and refusing) Cartesian representations of daily life: When mobile and grid epistemologies of the city meet. Cognition and Instruction, 38(3), 407-426.

Taylor, K. H. (2017). Learning along lines: Locative literacies for reading and writing the city. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 26(4), 533-574.

Taylor, K. H., & Hall, R. (2013). Counter-mapping the neighborhood on bicycles: Mobilizing youth to reimagine the city. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 18, 65-93.

Toliver, S. R. (2021). Recovering Black storytelling in qualitative research: Endarkened storywork. Routledge.

Vakil, S., & McKinney de Royston, M. (2022). Youth as philosophers of technology. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 29(4), 336-355.

Vélez, V., & Solórzano, D. G. (2017). Critical race spatial analysis: Conceptualizing GIS as a tool for critical race research in education. Critical race spatial analysis: Mapping to understand and address educational inequity, 8-31.