by C.V. Dolan

Abstract

Nonbinary students face necropolitical (Mbembe, 2019), or death-making, realities in education and broader society. Rooted in Mbembe’s theory and bolstered by education scholars (Torres, 2022; Williams et al., 2021), I define these necropolitics as interlocking systems of capitalist exploitation, white supremacy, cisheteropatriarchy, homonornativity and transnormativity, and binarism. I forefront intersectionality theory (Collins, 2017, 2019; Crenshaw, 1989, 1991) and queer of color critique (Blockett, 2019; Cohen, 1997; Ferguson, 2004; Muñoz, 1999, 2009) as epistemologies to explore dystopian educational realities for nonbinary students. Using a politics of refusal (Nicolazzo, 2017; Tuck & Yang, 2014), I turn to a new methodology, freedom-dreaming, to explore nonbinary students’ perspectives of gender utopia in education. As a combination of critical and embodied phenomenologies (Merleau-Ponty, 1962; Weiss et al., 2020) with arts-based methods (CohenMiller, 2018; Cole & Knowles, 2008), freedom-dreaming can introduce emancipatory opportunities to empirically explore nonbinary students’ visions for utopia.

Introduction

On their Netflix show Getting Curious, Jonathan Van Ness, a nonbinary white celebrity, asked Alok Vaid-Menon, a nonbinary person of color and scholar-activist: “What is it about nonbinary people and trans people that is so threatening to these systems of power?” Alok responded: “We represent possibility. We represent choice, being able to create a life, a way of living, a way of loving, a way of looking that’s outside of what we’ve been told that you should be” (Van Ness et al., 2022). This discussion illustrates an asset-based framework for understanding nonbinary and trans people’s existence and highlights the power we as nonbinary communities wield. We subvert binary assumptions, identities, and ways of being; we tear down binary ways of thinking and understanding the world; and we have collectively dreamed ourselves into existence in a world hostile toward us.

Nonbinary people are under attack in our families, in classrooms, in public spaces, and via the legislature (James et al., 2016). Despite this violence, nonbinary communities persist and refuse to disappear or betray our truths for a more palatable binary gender presentation or self-identification. As education landscapes and broader U.S. society sink deeper into necropolitics (Mbembe, 2019), or death-making realities (Torres, 2022; Williams et al., 2021), nonbinary students are uniquely poised to dream of new futures and worlds free of exploitation and harm.

In opposition to queerphobic and transphobic violence, Muñoz (2009) defined queer utopia as a vehicle for historically grounded and educated hope that establishes the base for collective revolutionary organizing. Often restricted to the realm of critical theory, I propose empirical explorations of utopia as defined by nonbinary students through freedom-dreaming (Kelley, 2002) as a methodology. Aligning with a politics of refusal to elicit and recount stories of pain and trauma (Tuck & Yang, 2014), I align my inquiry with explorations of nonbinary joy, hope, and liberation.

Purpose

In this article, I utilize Muñoz’ (2009) concept of queer utopia to critique and refuse the current capitalist, white supremacist, cisheteropatriarchal, homonormative, and binarist violence that nonbinary people face in educational systems in the U.S. The project of utopia starts with naming current dystopian and necropolitical (Mbembe, 2019), or death-making, realities for nonbinary communities. Adopting a politics of trans refusal, I offer a phenomenological turn away from studying the normative and queer/transphobic violence (Ahmed, 2006) that we as queer, trans, and nonbinary communities experience in education. Instead, I orient myself toward the horizon of queer futurity (Muñoz, 2009), manifesting possibility, hope, liberation, and utopia. I propose the use of a new blended methodology that weaves hermeneutic, critical, queer and trans phenomenologies with arts-based research as inherently queer modes of inquiry. This methodological bricolage provides a theoretically grounded approach for studying freedom dreams (Kelley, 2002), or utopian visions for liberatory worlds and possibilities (Muñoz, 2009).

Positionality

I situate myself as a simultaneously highly privileged person with multiple marginalized identities and experiences. I am a queer bisexual, nonbinary transgender person who is both white and Latinx. I have experienced extensive cissexism and binarism as a student and professional; I have witnessed and acted as an advocate alongside nonbinary students and communities in my professional roles in queer and trans campus resource centers; and I am eager to bring their experiences into literature. Now, as a Ph.D. candidate in education, I am particularly interested in nonbinary college students’ experiences, pathways, and visions for better worlds.

I recognize those who were not granted the privileges that I benefit from, who are not afforded the opportunity to contribute to this discourse. In that vein, I am wary of the whiteness centered in the majority of queer and trans student experience literature and the normative nature of the topic of student success. I seek to agitate the binary conceptualizations of success/failure, retention/attrition, graduation/dropout, grit/unqualified, among others. I ground myself in the knowledge that cisheteropatriarchy and binarism are steeped in and cannot be separated from other interlocking systems of oppression, such as white supremacy and capitalism. My embodied knowledge as a person who is white and mixed, queer, and trans guide me as I explore nonbinary utopia.

Epistemology: Intersectionality and Queer of Color Critique

As a researcher, I do not believe in a neutral stance or approach to empirical study. Epistemologically, I combine intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989, 1991; Collins, 2019) and queer of color critique (Blockett, 2019; Cohen, 1997; Ferguson, 2004; Muñoz, 1999, 2009) to elucidate entrenchments of power and entanglements of oppression. Using intersectionality as a heuristic to analyze and understand power, I de-center dominant perspectives, and re-center those most marginalized (Collins, 2019). Facing cisheteropatriarchal racism, nonbinary BIPOC face worse life outcomes and are at higher risk for violence and murder than white nonbinary people (James et al., 2016).

Queer of color critique theorists combine queer theory with intersectionality to analyze white supremacy, queerphobia and transphobia, and heteronormativity and cisnormativity (Blockett, 2019; Cohen, 1997; Ferguson, 2004). I use queer of color critique by primarily drawing from Muñoz’s (1999) theory of disidentification and worldmaking. Disidentification defies assimilation to white cisheterosexist expectations and instead engages in building queer worlds in community. Worldmaking is a radical act of looking toward and co-curating utopias in queer of color kinship communities (Muñoz, 2009).

Theoretical Framework: Necropolitics, Refusal, Abolition, and Freedom-Dreaming Utopia

In this section, I weave my theoretical framework and pertinent literature to illuminate the structures and systems that create dystopian realities for nonbinary college students. I discuss the necropolitical landscape within higher education, especially for disabled, queer, trans, BIPOC, undocumented, and other minoritized people (Squire et al., 2021; Torres, 2022). Using intersectionality theory and queer of color critique as prisms, I define these necropolitics by articulating how capitalist exploitation, white supremacy, cisheteropatriarchy, binarism, and homonormativity and transnormativity interlock.

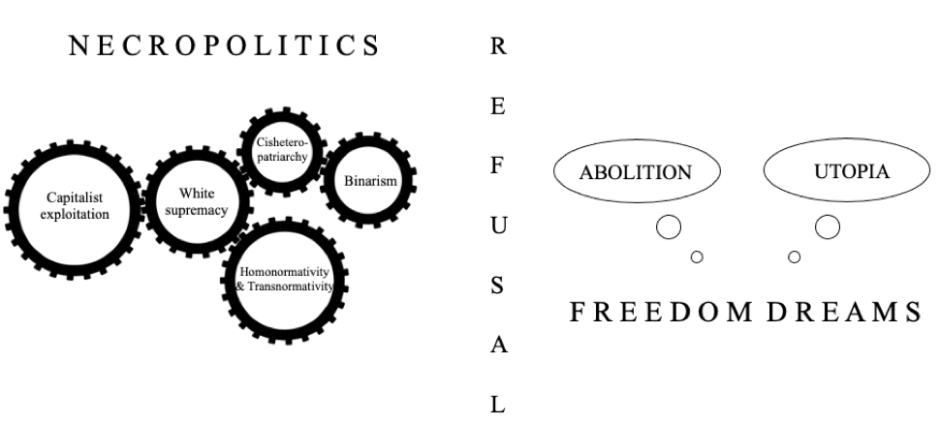

I propose refusal, freedom-dreaming, and queer and trans futurity projects as strategies for rejecting current dystopian realities. I name that our existence as nonbinary, an identity often deemed invalid by the pervasive and hegemonic binary gender norm in U.S. society, deems us as ideal communities to dream of new ways of being in the world. Scaffolded by this framework, this study seeks to illuminate and uncover the freedom-dreams nonbinary college students have of postsecondary education. See Figure 1 for a visual depiction of my conceptual framework.

Figure 1

Theoretical Framework

Higher Education: A Necropolitical Landscape

As a higher education and student affairs scholar, I align myself with academics and activists who believe that education can and should be a conduit for liberation for minoritized communities (Freire, 2011; hooks, 2003). However, education systems indulge in necropolitics, deeming certain subjects in the academy worthy of life or death (Mbembe, 2019; Torres, 2022). I use necropolitics as a theoretical frame to trace the ways power designates death-making realities in higher education and how colleges and universities act as death-making institutions (Torres, 2022). For the purposes of my project, I define the necropolitical landscape as the interlocking systems of capitalist exploitation, white supremacy, cisheteropatriarchy, binarism, and homonormativity and transnormativity. In the following subsection, I detail how these systems create interlocking necropolitical machinery and permeate nonbinary student realities, especially for QTBIPOC, in higher education (Torres, 2022).

Capitalist Exploitation in Higher Education

Often framed as training docile workers to compete in and contribute to a “free market” (Giroux, 2013), U.S. education networks are deeply entrenched in capitalist exploitation. U.S. universities endorse pluralism and neoliberal, or market-driven and corporate, models of education (Giroux, 2013; Greyser & Weiss, 2012). Higher education scholars often consider career placement as primary success outcomes in research studies (Stewart, 2021), and many researchers and educators believe that the highest form of utility is employment, job placement, and income potential for college graduates (Giroux, 2013).

Living under the realities of a years-long global pandemic with millions of deaths worldwide, higher education leaders and administrators have demonstrated that their priorities for ‘student success’ are thinly veiled urgencies to generate capital and compete for rankings, while engaging in performative policy shifts regarding masking and vaccinations for campus communities (Collier et al., 2020; Felson & Adamczyk, 2021). Decisions about reopening campuses were related to budget and political concerns, not COVID-19 infection and mortality rates (Felson & Adamczyk, 2021). Additionally, institutions’ decisions about modes of instruction were found to be correlated with White student enrollment or the state governor’s political party, rather than rates of infection or hospitalization (Collier et al., 2020).

Whether it be due to distance learning or the highly stressful experience of trying to survive during a global pandemic broadly, students report higher anxiety, less learner engagement, and less belonging than before (Charles et al., 2021; Tice et al., 2021). Additionally, many institutions have fired, laid off, or furloughed staff (Bauman, 2021; Chronicle Staff, 2020); cut raises including those to follow cost of living and inflation (Swartz, 2020); and continued to bust potential staff or faculty unions (Avery & Kinsella-Walsh, 2020). Even before the most recent COVID-19 pandemic, many argued that higher education has turned into a capitalist, dystopian, death-making machine (Giroux, 2013).

White Supremacy: A Legacy of Settler Colonialism and Anti-Blackness in Education

The founding of U.S. institutions of higher education is inseparable from colonization and enslaved labor (Williams et al., 2021). As land-grab institutions and settler academies (Morgensen, 2012) on stolen Indigenous land, our institutions are tools of colonization (paperson, 2017) with abysmal attendance and graduation rates for Native people (Postsecondary National Policy Institute, 2019). The legacy of U.S. institutions of education is steeped in the history of young Indigenous children stolen from their families and sent to boarding schools where they were tortured or killed when they spoke their Native languages, practiced cultural rituals, or resisted colonial teachings (Golash-Boza, 2018). Meanwhile, Indigenous nations, tribes, and communities were sent to reservations and/or attacked and killed as the U.S. government commodified and stole Indigenous land (Golash-Boza, 2018). This land was parceled to white families under the Homestead Act and to construct and fund public universities under the Morrill Act in 1862 (paperson, 2017). Enslaved Africans cleared the lands for and built many of our modern university buildings, though they were forbidden from attending schools (Golash-Boza, 2018).

Even after enslaved people were emancipated, racial segregation and Jim Crow laws forbade Black people from attending schools with whites. By the time the Supreme Court ended segregation in schools via Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), racial integration efforts resulted in the closing of most Black schools, most Black teachers losing their jobs, and Black students being bused to white schools and facing discrimination and violence (Golash-Boza, 2018). This segregation and subsequent desegregation permeated higher education through the creation and subsequent devaluing of minority-serving institutions (Gasman et al., 2015).

College campuses have become increasingly policed and militarized places, which are highly unsafe and often death-making environments for BIPOC, queer and trans, and undocumented people (Garvey & Dolan, 2021; Squire et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2021). Most institutions employ and deputize campus police forces and work with local forces (Johnson & Dizon, 2021). Colleges and universities often comply with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) forces, criminalizing and refusing to create sanctuary for undocumented students (Johnson & Dizon, 2021). Additionally, most institutions invest their endowments in prisons and detention centers, gun manufacturers, fossil fuel companies, and companies that employ sweatshop labor (Comrie, 2021).

Seen as exemplary spaces that separate and elevate the “exceptional” marginalized students from the rest, college campuses are steeped in white supremacy culture (Jones & Okun, 2016). This white supremacy culture is structural, thereby transcending the individual and interpersonal dynamics of BIPOC students’ experiences of belonging, impressions of campus climate, involvement, and rates of graduation and retention. Nonbinary students, especially nonbinary students of color, experience multiple systems of oppression, all of which are rooted in white supremacy. In the following subsection, I discuss cisheteropatriarchy and its connection to trans necropolitics in the academy.

Cisheteropatriarchy: Trans Killability and Disposability

Living in a cisheteropatriarchal and binarist society, trans people are treated as disposable, killable, and only worth discussing when we are sharing stories of suffering (Nicolazzo, 2021a, 2021c; Snorton & Haritaworn, 2013). This is especially true for trans femmes of color, particularly Black trans women and femmes, as this community faces transmisogyny (Serano, 2007), misogynoir (Bailey, 2021), and transmisogynoir (Krell, 2017).

Though some U.S. media have reported that we are currently living in a transgender tipping point, visibility does not protect trans people from danger and death (Nicolazzo, 2017). Nicolazzo (2021a, 2021c) has discussed “ghost stories” and “the spectre of the tranny” in academia and higher education and reports the experience of being buried “under the weight of being simultaneously too much and not enough” (Nicolazzo, 2021a, p. 127). In fact, trans people are often considered invisible or hypervisible. Invalidated by binary gender rhetoric, told we are not “trans enough,” do not pass as our gender, or that our genders do not exist, we are invisible. Hypervisibility often takes the form of being “noticeably” trans, being “clocked” or “detectable” as trans, or being gender-ambiguous (Gossett et al., 2017). This hypervisibility often leads to physical violence, as many trans people, especially trans femmes and women of color, have been murdered while being bombarded with transphobic slurs (Gossett et al., 2017).

The American Medical Association declared trans homicide as an epidemic in 2019 (Rojas & Swales, 2019), and there is an annual “holiday,” Trans Day of Remembrance, to commemorate trans people who have been killed. In addition to the undeniable truth that trans people are subject to astronomical amounts of violence (James et al., 2016), critical queer and trans scholars have introduced queer and trans death studies, analyses that use necropolitics as a frame to illuminate the disposability of trans and queer lives in a capitalist, white supremacist, cisheteropatriarchal, binarist world (Haritaworn et al., 2014; Snorton & Haritaworn, 2013).

Binarism: The Invisibility and Hypervisibility of Nonbinary People

Many nonbinary people identify within the transgender community, and while we experience transphobia similar to trans women and trans men, we also experience a unique invisibility and hypervisibility. Bilodeau (2009) coined the term genderism to refer to institutional dynamics that uphold cisheteropatriarchal views that gender can only be experienced in a binary way, that all people are either men or women. I use the term ‘binarism’ in this project to illuminate the unique realities of nonbinary people living in a world where we are illegible and simultaneously hypervisible in a binary world.

Because nonbinary people are not part of the cisheteropatriarchal imaginary, we are rarely correctly seen or legible in our gender identities. Rather, the binarist lens renders nonbinary people invisible (i.e., cisgender people misperceiving and misgendering a nonbinary person as binary) or hypervisible as someone ambiguously gendered or unintelligible (Kean, 2021; Snorton, 2009). The gender binary has permeated the Western, cisheteropatriarchal, capitalist imaginary and thereby erased the possibility or potential for a nonbinary person to exist without nonbinary people explicitly making our identities known. Therefore, binarism relies on nonbinary people’s constant identity disclosure on an individual and interpersonal level (Linley & Kilgo, 2018). Kean (2021) refers to this constant disclosure process as “‘testimonial smothering’ where a trans person is unable to authentically show up in a space because they already know they will be misunderstood, which may create an unsafe situation” (p. 273). The act of constantly sharing one’s correct name and pronouns can be overwhelming, risky, and laborious for trans people who often also carry the anticipation of being misgendered and deadnamed, regardless of their disclosure efforts.

Structurally, institutions of higher education reinforce binarism through their services and cultural approaches to teaching and learning (Kean, 2021). Binary restrooms, locker rooms, athletics teams, and housing prevail across most campuses, and too few institutions offer gender-inclusive or non-gendered options for these resources (Beemyn, 2022; Garvey & Dolan, 2021). Additionally, binarism is present in curricula and classrooms where faculty continue to discuss anything from biology to social work in a gender binary framework. Trans and nonbinary students report high levels of harm and exclusion in student health and counseling centers when seeking resources (Beemyn, 2015; Linley & Kilgo, 2018). Trans and nonbinary students are frequently misgendered in medical spaces and encounter barriers and gatekeeping when attempting to access transition care (Beemyn, 2015). Additionally, medical transition care, such as hormone replacement therapy or surgeries, are rarely covered under university student or employee health insurance plans (Beemyn, 2022). Nonbinary and other trans students also face barriers to being properly named and gendered at their institutions unless there is a chosen names policy, and even fewer institutions collect pronouns or gender identities in addition to legal sex markers (Beemyn, 2022). This data collection would allow a trans and/or nonbinary student to be recognized and correctly counted in campus surveys, give them access to the proper services and resources, and ideally allow this information to be shared so faculty, advisors, and other support staff can properly gender them in classrooms and other campus interactions (Garvey & Dolan, 2021).

However, policies and third spaces for trans and nonbinary people are inclusion tactics rather than liberatory strategies (Ahmed, 2012). These policies and practices create potentialities for nonbinary and trans people to exist but do not topple the cisheteropatriarchy and binarism that pervade the institutions. These reformist strategies do not protect trans and nonbinary people from violence, whether that be institutional exclusion, discrimination, rejection, harassment, or assault. In the next subsection, I discuss homonormativity and transnormativity as assimilation tactics, which similarly do not offer freedom from erasure, violence, or death.

Homonormativity, Transnormativity, and Assimilation as Necropolitical Tactics

Duggan (2003) coined the term ‘homonormativity,’ referring to queer and trans people’s tactics to assimilate into hegemonic structures that are often built to serve cisgender heterosexual people and the concept of cisheterosexuality, broadly. Aiming to be palatable to cisheteropatriarchal societies, homonormative movements seek to blend in with rather than dissemble dominant hierarchies and systems of oppression. Homonormative agendas often center the importance of legal rights to marry, form a family unit and adopt, serve in the military, advocacy for equal treatment by law enforcement and in prisons or detention facilities (Conrad, 2014). Rather than subverting cisheteropatriarchal ways of being or celebrating pride in one’s queerness or transness, homonormative LGBTQ individuals and collectives seek acceptance from cisheteropatriarchy, marginalizing those who will never fit into normative frameworks, such as nonbinary, agender, QTBIPOC, intersex, asexual, bisexual, disabled queer and trans people, and others who do not fit in or ascribe to binary and organized conceptualizations of identity (Cohen, 1997). In these ways, homonormativity deems non-normative queers as disposable and killable in a necropolitical world (Haritaworn et al., 2014).

Transnormativity (Johnson, 2016) is a construct that projects an idea of a centralized and monolithic trans experience. Johnson (2016) noted that transnormativity can be an empowering set of guidelines for some binary trans people to access transition care; however, it also invalidates many trans, especially nonbinary, people’s experiences. Transnormativity may perpetuate impostor syndrome, or an internalization that one is not “trans enough” or “nonbinary enough” to claim these identity labels (Bradford & Syed, 2019). An internalized concept of transnormativity can be a method of assimilation within trans communities – meet our standards of transness or face rejection (Tatum et al., 2020).

Transnormativity prescribes specific experiences for trans men and trans women, following hegemonic binary gendered norms of masculinity and femininity. Therefore, transnormativity privileges trans women who can pass as women and trans men who pass as men. Often those who can pass have access to medical transition care, such as hormone replacement therapy. However, measuring someone’s transness by any metric is inherently dismissive of those who do not have access to trans-affirming healthcare and transition care. There is no threshold to be officially trans, and all trans identities and experiences are valid. Transnormativity also creates oppressive conditions for nonbinary people since there is no “normative” way to live outside the hegemonic gender binary.

Homonormative and transnormative politics are rife within higher education, as they are often at the core of how universities tolerate or employ diversity and inclusion tactics (Ahmed, 2012) for queer and trans people (Nicolazzo, 2017). Rather than consider how the environment is toxic to queer and trans people, postsecondary institutions create queer and trans resource centers, hire queer and trans employees, create administrative bloat by recruiting a diversity hire or Chief Diversity Officer (Tuitt, 2021), and celebrate queer and trans students through programs and graduation ceremonies. These same institutions rarely create queer and trans protective policies or commit to institutional change (Nicolazzo, 2017).

In opposition to homonormativity and transnormativity, queer politics center the needs of the most marginalized, thereby fighting for the rights of all queer and trans people. Taking a more structural approach, queer liberation focuses on dismantling capitalist exploitation; state-sanctioned violence through police, ICE, the military, and state surveillance; and punishment through prisons and detention centers (Conrad, 2014). This stance focuses on ending criminalization, subjugation, and exploitation, not working within these oppressive structures to make them slightly less oppressive for a privileged few. Being homonormative will not liberate queer and trans communities; however, we will co-curate a new world through intersectional analyses and organizing, refusing dystopias, and freedom-dreaming.

Refusal: Pivoting Away from Necropolitics and Toward Utopia

Refusal is a political stance, pedagogy, research approach, and analytic practice that is rooted in Indigenous research ontologies and methodologies (Simpson, 2007; Tuck & Yang, 2014). Refusal “addresses forms of inquiry as invasion” (Tuck & Yang, 2014, p. 811) and rejects necropolitics as the primary frame for understanding marginalized experiences. Often, researchers who study nonbinary college students publish stories of pain, humiliation, rejection, invisibility. In response, Tuck and Yang (2014) refuse to serve

pain stories on a silver platter for the settler colonial academy, which hungers so ravenously for them. Analytic practices of refusal involve an active resistance to trading in pain and humiliation, and supply a rationale for blocking the settler colonial gaze that wants those stories. (p. 812)

In recognizing settler colonialism as an ongoing project in higher education and research as rooted in a hegemonic process of extraction, I join trans researchers who reject and refuse to conform to common queer and trans college student research narratives (Kean, 2021; Nicolazzo, 2017, 2021b). Using refusal as a pivot point and phenomenological turn away from the current dystopian realities as the only topics of empirical study, trans and nonbinary communities are free to dream of liberatory futures and new ways of being.

Freedom-Dreaming: Radical Imaginings and Visions

“Without new visions we don’t know what to build, only what to knock down. We not only end up confused, rudderless, and cynical, but we forget that making a revolution is not a series of clever maneuvers and tactics but a process that can and must transform us.” (Kelley, 2022, p. xii)

Abolition: Radical Destruction and Reconstruction

Abolitionist thinkers, activists, science fiction writers, and dreamers inspire and motivate me most in my mission, vision, and values as an educator and researcher. Built on the principles of tearing down harmful structures, such as enslavement, prisons, police, militaries, and surveillance (Davis, 2003), abolitionists also dream something new in the place of those systems. Abolitionists examine the root causes of systemic oppression and demand not only different outcomes but transformed systems and societies (Davis, 2016; Kaba, 2021).

Abolitionists not only want to end the necropolitical systems; we seek to build new ways of being in community where everyone can thrive (Kaba, 2021; Love, 2019). This often involves centering the needs of the most marginalized by our society. Abolitionists know and unapologetically demand that everyone has the right to survive and that human worth is not tied to income, debt, assets, level of education, identity, or ‘criminal’ activity (Kaba, 2021). Freedom-dreaming is an abolitionist strategy (Kaba, 2021; Kelley, 2002; Love, 2019) that requires imagination and courage to think past and outside of current structures and systems, inventing something new in its place. According to Muñoz (2009):

The way to deal with the asymmetries and violent frenzies that mark the present is not to forget the future. The here and now is simply not enough. Queerness should and could be about a desire for another way of being in the world and time, a desire that resists mandates to accept that which is not enough. (p. 96)

Through freedom-dreams, queer, trans, and nonbinary people can explore their radical imaginations and illuminate new worlds, or utopias, free of violence and harm.

Queer and Nonbinary Utopias: Futurity, the Radical Imagination, and Trans Worldmaking

Queer and trans theorists have studied and uplifted utopias as sites of and tactics for liberation (Muñoz, 2009; Nirta, 2017). These theorists lack consensus on the definition of utopia as a place-based, time-based reality that exists in the present (Nirta, 2017) or will always exist in the future (Muñoz, 2009). Muñoz (1999, 2009) named the importance of world-building for queer people and framed queerness itself as utopia. Perpetually on the horizon, Muñoz (2009) rooted utopia in hope, longing, striving, and becoming. Meanwhile, Nirta (2017) articulated the importance of queer and trans utopia as a present and current reality. Rather than treating the concept as asymptotic, never fully reaching a potential reality, Nirta (2017) argued that defining utopia only in the future drains its generative power. However, through my nonbinary ontology, I celebrate this discord and embrace the chaos, rather than view this disagreement as fracturing, deficit-based, or as a compulsion to choose one theorist’s definition.

Queer, trans, and nonbinary utopia is “an insistence on something else, something better, something dawning” (Muñoz, 2009, p. 189). A radical act of trans worldmaking, nonbinary utopia involves refusing the necropolitical present, envisioning abolitionist deconstruction, and committing to radically imagining new futures. I reject a Western entanglement of futurity with modernity, thereby erasing Indigenous cultures who have been freedom-dreaming for time immemorial. I acknowledge and uplift Indigenous queer, trans, and two-spirit people in this work, and I emphasize the value of bringing our queer and trans ancestors into our collective freedom-dreaming (Coleman, 2021), remembering that they are with us and part of our pasts, present, and futures. I embrace queer and trans BIPOC theorists (Love, 2019; Muñoz, 1999, 2009; Okello et al., 2021) as I explore the radical imagination as a strategy and homeplace for freedom-dreaming.

Freedom-Dreaming Toward Utopia: A Methodological Bricolage

In this section, I propose freedom-dreaming as a new methodological bricolage in qualitative and arts-based inquiry. I describe the method as a combination of hermeneutic, embodied, critical, and queer phenomenologies with arts-based research. I discuss the ways that phenomenological arts-based methods integrate artistic expressions of an essence or lifeworld, and I name the ways queer utopian studies has been inspired by art. Queer utopia scholarship is largely theoretical, and I believe it can be studied empirically through freedom-dreaming. This requires a rejection of the current necropolitical world, a refusal to continue to tell stories of pain (Tuck & Yang, 2014), and a phenomenological and queer re-orientation (Ahmed, 2006) towards the future.

Hermeneutic Phenomenology

Instead of simply describing, hermeneutic phenomenology research and writing aims to “show, not tell,” breathing life into an experience and bringing the reader into contact with a phenomenon (van Manen, 2016). Therefore, hermeneutic phenomenological research and writing may be conceptualized as nontraditional, subverting expected headings and categories or rejecting excessive verbal descriptions for stories that evoke emotions (Moran, 2000). Instead, the writer leads the reader into the depths of the phenomena’s essences, encouraging the reader to feel the texture and emotions and be present in the experience rather than seek descriptions and positivist declarations (Merleau-Ponty, 1962; van Manen, 2016).

In this approach, hermeneutic phenomenologists meet with co-researchers rather than participants or subjects. Additionally, this methodology favors approaching data collection and knowledge co-generation as “genuine conversations” rather than interviews and “gatherings” rather than focus groups (Gadamer, 2012; van Manen, 2016). This is more than a linguistic shift but a paradigmatic change in the approach to collecting data. Hermeneutic phenomenologists refer to interviews as genuine conversations and focus groups as gatherings because the spirit of engagement in these meetings should be organic, authentic, and personable. There is no “researcher” and “subject” hierarchical dynamic, rather a meeting of co-investigators reflecting on their experiences (van Manen, 2016). Using semi-structured protocols, researchers bring guiding questions for genuine conversations but do not lead those dialogues. These genuine conversations and gatherings should be shared spaces, compelling the researcher to be led by the co-investigators in the study. This act will allow people to “fall into conversation or even to become involved in it” (Gadamer, 2012, p. 385), allowing essences of the experiences to emerge in an intimate and authentic setting.

Hermeneutic phenomenologists challenge the idea of epoche or bracketing adopted by transcendental phenomenologists, declaring that a researcher’s inquiring neutrality is neither possible nor preferred (Dahlberg et al., 2008; Moran, 2000; Pillow, 2003). The researcher’s subjectivity, especially when they have personal experiences with the phenomena they are studying, is valuable and part of the research process. Due to the interpretive nature of the methodology, the hermeneutic phenomenologist is a conduit, lens, translator, and visionary as the essences emerge from the research (van Manen, 2016). Hermeneutic phenomenologists interpret individuals and their experiences as interrelated and reliant on each other, stating that a researcher cannot exist outside of their own history, experiences, or pre-understandings of their lifeworld. Dahlberg and Dahlberg (2003) introduce bridling instead of bracketing, where “pre-understandings are restrained so they do not limit the researching openness” (Vagle, 2009, p. 591; emphasis in original). Rather than looking backward, as done during bracketing, bridling calls the researcher to look forward, directing “the energy into the open and respectful attitude that allows the phenomena to present itself” (Dahlberg et al., 2008, p. 130).

Embodied Phenomenology

Merleau-Ponty (1962) situated the body as a site of knowing and orienting in hermeneutic phenomenology. Radically opposing cartesianism, he focused on embodied wisdom and phenomena as embodied experiences, and he introduced the phenomenology of perceptions (Moran, 2000). This branch of phenomenology seeks to uncover what it means to have bodies, live in bodies, and how one’s body impacts the way one process and lives in the lifeworld (Merleau-Ponty, 1962; Moran, 2000).

An embodied phenomenology is imperative for studying trans people, as our experiences of gender identity are uniquely embodied (Bettcher, 2020; Rubin, 1998). Rather than taking an essentialist view of gender which declares that one’s sex assigned at birth must coincide with a socially scripted gender, an embodied phenomenology must recognize the intrinsic self-knowledge trans people have within and about their bodies. This embodied self-knowledge is sacred and facilitates living in alignment with one’s gender truth outside of cisheteropatriarchal or binarist norms and expectations of gender. One’s gender is felt and experienced by the individual first and foremost, and that person is the expert on their own gender even as they are exploring the contours of it (Bettcher, 2020; Rubin, 1998). Embodied phenomenologists recognize that there is knowledge in the body, traces of memories in the flesh, and a sacred and unmistakable wisdom beyond words and thoughts within each person’s body (Merleau-Ponty, 1962).

Critical Phenomenology

Critical scholars have critiqued Merleau-Ponty, Sartre, and other embodied hermeneutic phenomenologists for their white, cisgender, heteronormative, masculinist approaches to defining and engaging phenomenology (Ahmed, 2006; Rubin, 1998; Salamon, 2018). Fortunately, queer and trans scholars have embedded discursive analyses into an embodied phenomenological approach to use when studying queer and trans phenomena, resulting in a series of critical approaches (Ahmed, 2006; Bettcher, 2020; Rubin, 1998). This approach carves space for returning legitimacy to self-knowledge and embodied wisdoms of trans people, re-orienting trans people and their bodies as sources of legitimate and legitimizing knowledge (Rubin, 1998).

While many transcendental and hermeneutic phenomenologists have rejected the role of theory in this methodological approach, critical phenomenologists embrace theory as an epistemological tool. It is here that critical theory and phenomenology come into contact. Critical phenomenologist Salamon (2018) contended: “…if phenomenology offers us unparalleled means to describe what we see with utmost precision, to illuminate what is true, critique insists that we also attend to the power that is always conditioning that truth” (p. 15). By recognizing the role of power, hegemony, and privilege, critical phenomenologists commit to studying the lifeworld with conscious awareness that the ways one is oriented toward phenomena is laced in power (Weiss et al., 2020).

Queer Phenomenology

In proposing a queer phenomenology, Ahmed (2006) named heteronormativity as an inscription device to make heterosexuality an unmarked and expected orientation in Western colonized societies (Burke, 2020; Guilmette, 2020). Ahmed (2006) explains: “The naturalization of heterosexuality involves the presumption that there is a straight line that leads each sex toward the other sex, and that ‘this line of desire’ is ‘in line’ with one’s sex” (pp. 70-71; emphasis in original). She added: “The naturalization of heterosexuality as a line that directs bodies depends on the construction of women’s bodies as being ‘made’ for men, such that women’s sexuality is seen as directed toward men” (p. 71) and declared “heterosexuality as a ‘compulsory orientation’” (p. 71). While compulsory heterosexuality is not a new term as of Ahmed’s (2006) work (Butler, 1990; Rich, 1980), her reading of this as a compulsory phenomenological orientation and method is key to developing my methodological structure.

Ahmed (2006) named that the heteronormative inscription device can make even queer bodies appear straight:

…if the inverted woman is really a man, then she, of course, follows the straight line toward what she is not (the feminine woman). So the question is not only how queer desire is read as off line, but also how queer desire has been read in order to bring such desire back into line… Such readings function as ‘straightening devices,’ (pp. 71-72)

Taking this line of reason further, I offer that cisnormativity is intrinsically wrapped with heteronormativity. Given that heteronormativity is the concept that men and women are attracted to each other, cisnormativity assumes that all men and women are also cisgender. Additionally, cisnormativity and cissexism render trans people or anyone outside of binary gender identities invisible. Therefore, a cisheterosexist inscription device renders cisgender heterosexual orientations as the only visible and legible orientations in society. Ahmed (2006) referred to queerness in this paradigm as a disorientation.

Many scholars cite the body as a site of gendered performativity (Butler, 1990; Hansen, 2020; Sedgwick, 1993) to send messages about one’s gender expression to be perceived in alignment with one’s gender identity. However, nonbinary people do not have a gender archetype in the Western, white, colonial, cisnormative gaze which assumes all genders are binary (Guilmette, 2020; Smith, 2010). Therefore, to turn toward nonbinary people is an inherently queer orientation, to look toward a gendered liminality (Muñoz, 2009), to make visible and legible new genders and eradicate the false gender binary.

Weaving Phenomenologies and Arts-Based Research

Combining aspects of hermeneutic (van Manen, 2016), embodied (Merleau-Ponty, 1962), critical (Weiss et al., 2020), and queer (Ahmed, 2006) phenomenologies with arts-based methods (CohenMiller, 2018; Cole & Knowles, 2008), freedom-dreaming introduces emancipatory opportunities to empirically explore nonbinary students’ visions for utopia. By studying alongside co-investigators, rather than extracting information from subjects, in genuine conversations and gatherings, rather than interviews and focus groups, hermeneutic phenomenologists flatten hierarchy in the research process (van Manen, 2016). Merleau-Ponty (1962) refocused inquiry by rejecting capitalist and cartesian splits of the mind and body, resituating the body as a site of knowledge and wisdom. Critical phenomenologists integrate theory as a prism to collect and analyze data, and queer phenomenologists (Ahmed, 2006) encourage researchers to recognize cisheteropatriarchy as an inscription device in society and the research process.

Blending these phenomenological strands with arts-based research provides a unique opportunity to encourage co-investigators to dream, envision, and experience a queer utopia or horizon. As a performance studies scholar, Muñoz (1999, 2009) was inspired by drag, dance, photography, graffiti, poetry, and other queer artistic expressions in his definitions of queer utopia. While queer utopia studies are currently relegated to the realm of critical theory, the ways in which queer utopia has been inspired by art creates an entry point for empirical study through phenomenological arts-based research.

Arts-based researchers encourage co-investigators to share artistic representations of research topics (Cole & Knowles, 2008). With phenomenologists’ goal of capturing the essence of a shared phenomenon, artistic methods can bring investigators more directly into contact with the lifeworld of those who share an experience (Wrathall, 2011). Unflattening verbal and written language as the only forms of communication, art elucidates truth (Crowell, 2011; Wrathall, 2011).

I encourage researchers to empirically study queer, trans, and nonbinary utopias through phenomenological arts-based freedom-dreaming. Ask co-investigators about their vision for a nonbinary utopia in a postsecondary landscape. Co-investigators may share reformist ideas for incremental change, articulate a fear of failure, or feel entrenched in scarcity mentalities. How can we as researchers disidentify (Muñoz, 1999) with the ways capitalism, white supremacy, cisheteropatriarchy, binarism, homonormativity, and transnormativity restrict our imaginations for what we deserve and what is possible?

Therefore, this methodology requires the researcher to continually heal from internalized violence and support co-researchers in their healing process as we dare to turn away from the necropolitical realities and abundantly dream of liberation. Perhaps co-researchers will propose abolition of the project of higher education as we know it, envisioning new ways to rebuild or resituate utopia in a postsecondary framework outside of current college contexts. Anything is possible when we allow ourselves and our co-investigators to radically dream of new worlds where we are free from capitalist, white supremacist, cisheteropatriarchal, binarist, homonormative, and transnormative violence.

Conclusion

Capitalist exploitation, white supremacy, cisheteropatriarchy, homonormativity and transnormativity, and binarism interlock to create death-making realities for nonbinary students. Using a politics of trans refusal (Nicolazzo, 2017), researchers can explore freedom-dreaming (Kelley, 2002) as an onto-methodological approach to study nonbinary students’ visions of utopia. As a methodology, freedom-dreaming can be used to bring utopia out of the strict confines of critical theory literature and introduce it into empirical inquiry. As a methodological tool, freedom-dreaming builds a platform for new, innovative, and liberatory forms of research.

Notes on Contributors

Dolan (they/them/theirs) is a white and Latinx, queer, nonbinary Ph.D. candidate in Educational Leadership and Policy Studies at the University of Vermont. Their dissertation explores nonbinary college students’ freedom dreams of gender utopia in post-secondary landscapes. They are currently teaching graduate courses and researching sexual orientation and gender identity data collection on college campuses for their graduate research assistantship. Dolan is an aspiring mixed methodologist with the long-term goal of serving as a tenure-track faculty in a Higher Education and Student Affairs Administration graduate program upon completing their doctoral degree in 2024.

References

Ahmed, S. (2006). Queer phenomenology. Duke University Press.

Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press.

Avery, C., & Kinsella-Walsh, M. (2020). Union-busting during a pandemic could become deadly. Jacobin. Retrieved from https://jacobinmag.com/2020/03/coronavirus-oberlin-college-union-busting-student-organizing/

Bailey, M. (2021). Misogynoir transformed: Black women’s digital resistance. New York University Press.

Bauman, D. (2021, February 5). A brutal tally: Higher ed lost 650,000 job last year. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/a-brutal-tally-higher-ed-lost-650-000-jobs-last-year

Beemyn, G. (2015). Coloring outside the lines of gender and sexuality: The struggle of nonbinary students to be recognized. The Educational Forum, 79(4), 359-361. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2015.1069518

Beemyn, G. (2022). Campus pride trans policy clearinghouse. Retrieved from https://www.campuspride.org/tpc

Bettcher, T. M. (2020). Trans phenomena. In G. Weiss, A. V. Murphy, & G. Salamon, A. V. Murphy (Eds.), 50 concepts for a critical phenomenology (pp. 329-336). Northwestern University Press.

Bilodeau, B. (2009). Genderism: Transgender students, binary systems, and higher education. VDM Verlag.

Blockett, R. A. (2018). Thinking with queer of color critique: A multidimensional approach to analyzing and interpreting data. In R. Winkle-Wagner, J. Lee-Johnson, & A. Gaskew (Eds.), Critical theory and qualitative data analysis in education (pp. 127–140). Routledge.

Bradford, N. J., & Syed, M. (2019). Transnormativity and transgender identity development: A master narrative approach. Sex Roles, 81, 306-325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0992-7

Burke, M. (2020). Heteronormativity. In G. Weiss, A. V. Murphy, & G. Salamon, A. V. Murphy (Eds.), 50 concepts for a critical phenomenology (pp. 161-167). Northwestern University Press.

Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge.

Charles, N. E., Strong, S. J., Burns, L. C., Bullerjahn, M. R., & Serafine, K. M. (2021). Increased mood disorder symptoms, perceived stress, and alcohol use among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Research, 296(2021), 113706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113706

Chronicle Staff. (2020, May 13). As COVID-19 pummels budgets, colleges are resorting to layoffs and furloughs. Here’s the latest. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/were-tracking-employees-laid-off-or-furloughed-by-colleges/

Cohen, C. J. (1997). Punks, bulldaggers, and welfare queens: The radical potential for queer politics? GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 3(4), 437-465. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-3-4-437

CohenMiller, A. S. (2018). Visual arts as a tool for phenomenology. Forum Qualitative, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.1.2912

Cole, A. L., & Knowles, J. G. (2008). Arts-informed research. In J. G. Knowles, & A. L. Cole (Eds), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 55-70). Sage.

Coleman, J. J. (2021). Restorying with the ancestors: Historically rooted speculative composing practices and alternative rhetorics of queer futurity. Written Communication, 38(4), 512-543. https://doi.org/10.1177/07410883211028230

Collier, D. A., Fitzpatrick, D., Dell, M., Snideman, S. S., Marsicano, C. R., Kelchen, R., & Wells, K. E. (2021). We want you back: Uncovering the effects on in-person instruction operations in Fall 2020. Research in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-021-09665-5

Collins, P. H. (2019). Intersectionality as critical social theory. Duke University Press.

Combahee River Collective. (1977). The Combahee River Collective statement. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/combahee-river-collective-statement-1977

Conrad, R. (Ed.). (2014). Against equality: Queer revolution not mere inclusion. AK Press.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. The University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–167. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Crowell, S. (2011). Phenomenology and aesthetics; or, why art matters. In J. D. Parry (Ed.), Art and phenomenology (pp. 31-53). Routledge.

Dahlberg, H., & Dahlberg, K. (2003). To not make definite what is indefinite: A phenomenological analysis of perception and its epistemological consequences. Journal of the Humanistic Psychologist, 31(4), 34-50. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873267.2003.9986933

Dahlberg, K., Dahlberg, H., & Nystrom, M. (2008). Reflective lifeworld research (2nd ed.). Studentlitteratur.

Davis, A. Y. (2003). Are prisons obsolete? Seven Stories Press.

Davis, A. Y. (2016). Freedom is a constant struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the foundations of a movement. Haymarket Books.

Duggan, L. (2003). The twilight of equality?: Neoliberalism, cultural politics, and the attack on democracy. Beacon Press.

Felson, J., & Adamczyk, A. (2021). Online or in person? Examining college decisions to reopen during the COVID-19 pandemic in Fall 2020. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 7, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023120988203

Ferguson, R. A. (2004). Aberrations in Black: Toward a queer of color critique. University of Minnesota Press.

Freire, P. (2011). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th anniversary ed.). Continuum.

Gadamer, H-G. (2012). Truth and method (2nd ed.). Continuum.

Garvey, J. C., & Dolan, C. V. (2021). Queer and trans college student success: A comprehensive review and call to action. In L. W. Perna (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 36, pp. 161-215). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43030-6_2-1

Gasman, M., Nguyean, T-H., & Conrad, C. F. (2015). Lives intertwined: A primer on the history and emergence of minority serving institutions. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 8(2), 120-138. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038386

Giroux, H. A. (2013). Beyond dystopian education in a neoliberal society. Fast Capitalism, 10(1), 109-120. https://doi.org/10.32855/fcapital.201301.010

Golash-Boza, T. M. (2018). Race racisms: A critical approach (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Gossett, R., Stanley, E. R., & Burton, J. (2017). Trap door: Trans cultural production and the politics of visibility. MIT Press.

Greyser, N., & Weiss, M. (2012). Introduction: Left intellectuals and the neoliberal university. American Quarterly, 64(4), 787-793. https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2012.0064

Guilmette, L. (2020). Queer orientation. In G. Weiss, A. V. Murphy, & G. Salamon, A. V. Murphy (Eds.), 50 concepts for a critical phenomenology (pp. 275-282). Northwestern University Press.

Haritaworn, J., Kuntsman, A., & Posocco, S. (2014). Queer necropolitics. Routledge.

hooks, b. (2003). Teaching to transgress. Routledge.

James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. (2016). The report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. https://www. transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/USTS-Full-Report-FINAL.PDF

Johnson, A. H. (2016). Transnormativity: A new concept and its validation through documentary film about transgender men. Sociological Inquiry, 86(4), 465-491. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12127

Johnson, R. M., & Dizon, J. P. M. (2021). Toward a conceptualization of the college-prison nexus. Peabody Journal of Education, 96(5), 508-526. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2021.1991692

Jones, J. K., & Okun, T. (2016). Dismantling racism: A workbook for social change groups. dRworks. Retrieved from https://resourcegeneration.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/2016-dRworks-workbook.pdf

Kaba, M. (2021). We do this ‘til we free us: Abolitionist organizing and transforming justice. Haymarket Books.

Kean, E. (2021). Advancing a critical trans framework for education. Curriculum Inquiry, 51(12), 261-286. https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2020.1819147

Kelley, R. D. G. (2002). Freedom dreams: The Black radical imagination. Beacon Press.

Krell, E. C. (2017). In transmisogyny killing trans women of color?: Black trans feminisms and the exigencies of white femininity. TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 4(2), 226-242. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-3815033

Linley, J. L., & Kilgo, C. A. (2018). Expanding agency: Centering gender identity in college and university student records systems. Journal of College Student Development, 59(3), 359-365. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2018.0032.

Love, B. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

Martino, W., & Omercajic, K. (2021). A trans pedagogy of refusal: Interrogating cisgenderism, the limits of antinormativity and trans necropolitics. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 29(5), 679-694. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2021.1912155

Mbembe, A. (2019). Necropolitics. Duke University Press.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception. Routledge.

Moran, D. (2000). Introduction to phenomenology. Routledge.

Morgensen, S. L. (2012). Destabilizing the settler academy: The decolonial effects of Indigenous methodologies. American Quarterly, 64(4), 805-808. https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2012.0050

Muñoz, J. E. (1999). Disidentifications: Queers of color and the performance of politics. University of Minnesota Press.

Muñoz, J. E. (2009). Cruising utopia: The then and there of queer futurity. New York University Press.

Nicolazzo, Z. (2017). Introduction: What’s transgressive about trans* studies in education now? International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(3), 211-216. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2016.1274063

Nicolazzo, Z. (2021a). Ghost stories from the academy: A trans feminine reckoning. The Review of Higher Education, 45(2), 125-148. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2021.0018

Nicolazzo, Z. (2021b). Imagining a trans* epistemology: What liberation thinks like in postsecondary education. Urban Education, 56(3), 511-536. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085917697203

Nicolazzo, Z. (2021c). The spectre of the tranny: Pedagogical (im)possibilities. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 29(5), 811-824. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2021.1912163

Nirta, C. (2017). Actualized utopias: The here and now of transgender. Politics and Gender, 13(2). 181-208. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X1600043X

Okello, W. K., Duran, A. A., & Pierce, E. (2021). Dreaming from the hold: Suffering, survival, and futurity as contextual knowing. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000321

paperson, l. (2017). A third university is possible. University of Minnesota Press.

Pillow, W. S. (2003). Confession, catharsis, or cure? Rethinking the uses of reflexivity as methodological power in qualitative research. Qualitative Studies in Education, 16(2), 175-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839032000060635

Postsecondary National Policy Institute (PNPI). (2019). Native American students in higher education. https://pnpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/2019_NativeAmericanFactsheet_Updated_FINAL.pdf

Rich, A. (1980). Compulsory heterosexuality and lesbian existence. Signs, 5(4), 631-660. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3173834

Rojas, R., & Swales, V. (2019, September 27). 18 transgender killings this year raise fears of an ‘epidemic.’ New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/27/us/transgender-women-deaths.html

Rubin, H. S. (1998). Phenomenology as method in trans studies. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 4(2), 263-281. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-4-2-263

Salamon, G. (2018). The life and death of Latisha King: A critical phenomenology of transphobia. New York University Press.

Sedgwick, E. K. (1993). Queer performativity: Henry James’ The Art of the Novel. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 1, 1-16. Retrieved from https://queertheoryvisualculture.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/sedgwick_queerperformativity.pdf

Serano, J. (2007). Whipping girl: A transsexual woman on sexism and the scapegoating of femininity. Seal Press.

Simpson, A. (2007). On ethnographic refusal: Indigeneity, ‘voice,’ and colonial citizenship. Junctures: The Journal for Thematic Dialogue, 2007(9), 67-80.

Smith, A. (2010). Queer theory and Native studies: The heteronormativity of settler colonialism. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 16(1-2), 42-68. https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2009-012

Snorton, C. R. (2009). “A new hope”: The psychic life of passing. Hypatia, 24(3), 77-92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2009.01046.x

Snorton, C. R., & Haritaworn, H. (2013). Trans necropolitics: A transnational reflection on violence, death, and the trans of color afterlife. In S. Stryker & A. Aizura (Eds.), Transgender studies reader (2nd ed.). Routledge. Retrieved from http://wmst601fa17.queergeektheory.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/snorton-and-haritaworn.pdf

Squire, D. D., Williams, B. C., & Tuitt, F. A. (2018). Plantation politics and neoliberal racism in higher education: A framework for reconstructing anti-racist institutions. Teachers College Record, 120(14), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811812001412

Stewart, D-L. (2021). Afterword: Against higher education: Instruments of insurrection. In B. C. Williams, D. D. Squire, & F. A. Tuitt (Eds.), Plantation politics and campus rebellions: Power, diversity, and the emancipatory struggle in higher education (pp. 315-320). SUNY Press.

Swartz, K. (2020). Two days in, UCSB COLA wildcat strike draws close to 2,000 supporters. Daily Nexus. Retrieved from https://dailynexus.com/2020-02-28/two-days-in-ucsb-cola-wildcat-strike-draws-close-to-2000-supporters/

Tatum, A. K., Catalpa, J., Bradford, N. J., Kovic, A., & Berg, D. R. (2020). Examining identity development and transition differences among binary transgender and genderqueer nonbinary (GQNB) individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 7(4), 379-385. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000377

Torres, E. J. (2022). Higher education and necropolitics: Tracing death and violence in higher education. The Vermont Connection, 43, 126-147. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/tvc/vol43/iss1/15

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2014). Unbecoming claims: Pedagogies of refusal in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(6), 811-818. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414530265

Tuitt, F. A. (2021). The contemporary Chief Diversity Officer and the plantation driver: The reincarnation of a diversity management position. In B. C. Williams, D. D. Squire, & F. A. Tuitt (Eds.), Plantation politics and campus rebellions: Power, diversity, and the emancipatory struggle in higher education (pp. 171-197). SUNY Press.

van Manen, M. (2016). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Van Ness, J., Bailey, F., Barbato, R., Campbell, T., & Lane, J. (2022). Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness [Netflix]. https://www.netflix.com/title/81206559

Weiss, G., Murphy, A. V., & Salamon, G. (2020). 50 concepts for a critical phenomenology. Northwestern University Press.

Wiegman, R., & Wilson, E. A. (2015). Introduction: Antinormativity’s queer conventions. Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 26(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-2880582

Williams, B. C., Squire, D. D., & Tuitt, F. A. (2021). Plantation politics and campus rebellions: Power, diversity, and the emancipatory struggle in higher education. SUNY Press.

Wrathall, M. (2011). The phenomenological relevance of art. In J. D. Parry (Ed.), Art and phenomenology (pp. 9-30). Routledge.